Social Justice

This article is part of Camping Magazine's series on social justice, exploring social issues in the context of individual camps and the camp community as a whole as a way to spark further conversation and inspire positive change.

Contact Ann Gillard ([email protected]) if you would like to participate or contribute to this series.

You thought about working at camp, applied, got hired, and now you’re looking forward to creating positive relationships with campers all summer. We all know (and research shows) that positive youth-adult relationships are incredibly important building blocks for young people’s development. Growing up, you might have had an influential young adult or “near peer” in your life. Think about that person for a minute. Why did you like them? What did they do to influence or inspire you? Were they good listeners? Did it seem like they “got” you? Did they ever stand up for you?

This summer you have a tremendous opportunity to make a difference in the lives of children and youth. Did you know that you also can make a difference toward diversity, equity, and inclusion? You can! How? By being an ally to campers. Being an ally to campers means listening, noticing, reflecting, and taking action to change patterns of society’s injustices. Being an ally does not mean “saving” or pitying individuals or groups, or staying stuck in guilty and sad feelings about the way things are. In fact, the process of being an ally — allyship — is really just the start of a lifelong process of learning about patterns of injustice in our society. Of course, learning isn’t enough. Learning should lead to actively working to disassemble injustices while opening avenues for thriving.

Have you ever been worried about what to say if a camper says or does something that seems racist, sexist, or homophobic? Or what you would do if campers did or said something that seemed unintentionally dismissive or made someone feel self-conscious about their race, ethnicity, or gender? Some camp staff are afraid they might not know how to handle such situations. Yet, we all know that campers don’t leave oppressive attitudes or behaviors at the front gate, even if we’d like them to. Camp can be a place where children and youth learn from positive role models like you. Even better, campers can leave camp and go back out into the world emboldened to make a difference for others.

Obstacles

So, you’re committed to doing whatever you can to end the injustices in the world. Why might it be scary or hard to do this at camp?

- The topic doesn’t come up.

- We’ve never thought about how a group of people might experience injustice based on their membership in a social group.

- We’ve never thought about areas where people from our own social group might have unearned privilege, power, or advantages.

- We don’t understand someone else’s identity and experiences with that identity.

- We believe the myth that “at camp, everyone is the same” and forget that a) sometimes camps reinforce the unfair or negative ideas we have about social groups, and b) campers don’t always leave their closely held assumptions, social identities, or past experiences at the camp gate.

- We think these topics should be left to parents, teachers, or other professionals.

- We don’t want to sound ignorant, racist, or sexist, or make someone feel devalued or stereotyped.

- We think we need to be “saviors” of kids who need our help, and that seems like a big responsibility.

We need to recognize these obstacles so we can try to overcome them and help each other as camp staff to look for opportunities to move beyond these hurdles.

Targets and Agents

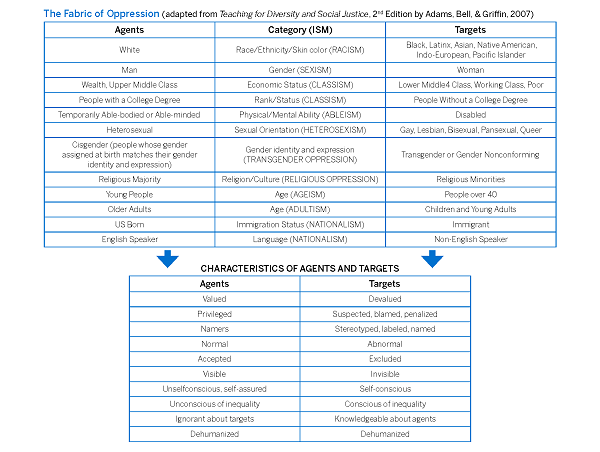

One way of thinking about groups treated unfairly is the idea of “targets” and “agents.” Targets of oppression are people in social identity groups who are considered to be inferior, disenfranchised, negatively valued, exploited, and/or victimized. Agents of oppression are people in social identity groups who are considered to be privileged by birth or acquisition who knowingly or unknowingly exploit and gain unfair advantage over people from targeted groups, and are seen as superior or “normal.” Target groups have little or no access to resources and social power, and agent groups have ample access to resources and social power (for more information on these definitions, see Additional Resources on page 25).

Following is a chart outlining the structural relationship between agents and targets through categories of “isms”(see The Fabric of Oppression on page 24). The idea of “fabric” refers to a larger structure containing patterns made up of smaller ties or connections woven from individual threads. As you look at the chart, think about the agent groups and target groups to which you belong. You will probably see that you are a member of groups on both the left and the right side of the chart. Note that being a member of an agent group doesn’t mean an individual is bigoted, discriminates, or is guaranteed power. Likewise, an individual member of a target group isn’t automatically oppressed or suffering.

Following the chart are arrows that point to the consequences of the fabric of oppression. Consequences are reflected in the emotions, feelings, and experiences of both agent and target groups.

Developing Positive Relationships

So, what should camp staff do? Following are some ideas to consider as you work toward developing positive relationships with campers and engaging in allyship.

Ongoing Work

- Educate yourself about issues facing people from target groups. If you find yourself in an agent group, read stories, news, and blogs by people from the target group. Attend community meetings, conferences, or educational opportunities if invited by associations of the target group, and spend your time there listening and learning.

- Become aware of your implicit associations and biases, such as by taking an implicit association test at Project Implicit.

- Speak with, not for, people from target groups. Find groups addressing injustices and ask them what you can do to help.

- Use the power you have as a camp counselor (and an agent) to guide the culture of your cabin to be one of celebration of diversity, equity, and fostering a sense of belonging. Comment on how awesome it is that there are so many differences in your cabin and how camp is a safe place for every camper to express themselves.

- Use the power you have as a voice for campers to ask about changing camp policies or procedures — such as dividing groups by gender when the activity has nothing to do with gender — to be fairer.

In the Moment

- If you overhear or witness an “ism” comment or action:

- Evaluate the comment or action to see if it seems to come from a place of ignorance or a place of meanness. Remember to react based on the ism it represents, not based on who’s in the room or whether you think the person who said it was trying to be offensive or not. Think about why it’s important to take action.

- Check to make sure the camper from the targeted group is okay or get them help.

- Educate the camper from the agent group making the comment about the reality of the situation in a way that aims to retain their dignity yet also builds empathy. You can point out that what was said has an effect, whether the camper meant it that way or not.

- Actively observe the verbal and nonverbal communication of campers from target groups to see if they are demonstrating characteristics such as feeling devalued, blamed, excluded, invisible, stereotyped, or self-conscious.

- If you hear or witness an ism from someone from an agent group, ask questions in a nonjudgmental, nonleading way to understand a camper’s thought process and not shut them down. Examples of probing questions could be “What makes you think that?” or “How do you feel about that?” or “What do you think that says about people from [targeted group]?”

- Acknowledge and name the ism that shows up in a conversation or interaction, even if you’re nervous about doing so. It helps to draw attention to the comment or behavior instead of the person. For example, “that comment supports sexism” instead of “you’re a sexist.”

- Use the concept of fairness. Kids are very concerned about what is fair and have a strong sense of justice. You can point out that the patterns or “rules” they see out in the world can be unfair to some people.

- If you start to feel disrespected or defensive, take a breath or a break and think about the other person’s perspective in terms of how and to what they show respect. Consider your own status in an agent group and your group’s historical patterns of relationship with the target group.

- If you’re not sure what to do, say so. And tell the camper how you’re going to think about this more or ask for some help. Role modeling how to handle difficult situations is a great tool for teaching campers productive problem-solving skills.

Being Proactive

- Point out positive role models. This will require you to educate yourself about people from target groups who have made a difference in the world.

- Help campers think about people as multidimensional and having lots of identities. Kids, especially younger ones, can easily latch onto yes-no reductionist thinking or reasoning and make assumptions that all people are like that, based on a sample of one.

- Read books or stories featuring a diverse range of characters and situations.

- Take campers’ interests, curiosities, and questions seriously and provide appropriate resources.

- Showcase the leadership of people with a variety of visible differences.

Taking Responsibility

If you’re reading this and thinking that allyship might not be enough to change patterns of injustice and systems of oppression, you’re right! It takes thoughtfulness, listening, and reflection followed by action and hard work. It’s about doing this work not only to help others for their sake, but to take responsibility as an agent to make sure your group is doing all it can to ensure that all groups experience freedom and justice.

At camp, you have the incredible opportunity to not only make a difference in the lives of individual campers, but in the lives of people from target groups who have faced oppression. A lot of us wish the rest of the world was like camp. Camps can be a powerful learning experiences for children (and staff) who seek to create a world that is fairer for everyone, where everyone can thrive.

Additional Resources |

|

Reference

Adams, M., Bell, L. A., & Griffin, P. (2007). Teaching for diversity and social justice, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.

Author’s Note: Special thanks to Erin Buzuvis and Emily Billings.

| Discussion Questions |

|

Ann Gillard, PhD, has worked in youth development and camps for over 20 years as a staff member, volunteer, evaluator, and researcher. Ann also organizes Camping Magazine’s Social Justice Series. If you would like to propose an article for the Social Justice Series, contact Ann at [email protected].