For over 110 years, resting on the belief that camp can be enriching for all kids, the American Camp Association (ACA) has dedicated itself to enriching the lives of children, youth, and adults through quality camp programs. Unfortunately, due to the opportunity gap, many young people and their families still face significant challenges when attempting to access summer camp. In this four-part series, we are excited to highlight recent research aimed at helping camp practitioners increase access to summer camp for all youth. In this issue, we will talk about summer camp as a developmentally enriching experience, the opportunity gap, and how we conceptualize the factors that impact participation in summer camp.

Throughout this series, we will be using a range of terminology to describe what we’ve learned. The following lexicon defines and clarifies what we mean by the different highlighted terms.

Lexicon

Achievement Gap: The achievement gap “refers to outputs — the unequal or inequitable distribution of educational results and benefits” (Glossary of Education Reform, 2013). This term places responsibility for achievement, or lack thereof, on the individual, rather than the systems influencing youth’s ability to succeed.

Constraints: All the factors that impact participation in summer camps, including preventing participation, reducing frequency, intensity, or duration of participation, or reducing the quality of experience or satisfaction gained from participation in summer camp. Constraints are categorized in three ways: psychological, social, and structural — and all are shaped by culture.

Negotiate: Traditionally meaning “to find a way over or through (an obstacle or difficult path),” in current constraint literature, when one works their way through or around a constraint, they have “negotiated” it. Put another way, they may have overcome an obstacle or navigated some sort of barrier to access.

Obstacles: Another word for “constraints.” Examples include poverty, distance between home and camp, transportation, childcare for younger siblings, and time.

Opportunity Gap: The opportunity gap “refers to inputs — the unequal or inequitable distribution of resources and opportunities,” such as differences in family income, wealth, and neighborhood resources; institutional and systemic sources of inequity; and racism, bias, and discrimination (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2019; Glossary of Education Reform, 2013). By highlighting the numerous obstacles children face over the course of their development, this term shifts the responsibility from youth and more accurately places it on systems of inequity that are not providing the opportunities for all children to thrive and succeed (Mooney, 2018).

Preference: Across multiple disciplines, “preference” serves as a technical term used in relation to choosing between alternatives. For example, a child may choose to audition for the afterschool play rather than try out for the soccer team because they have developed a preference for, or interest in, theatre. Preferences are central to decision-making due to their potential to drive behavior.

Socioeconomic Status (SES): The social standing or class of an individual or group. It is often measured as a combination of education, income, and occupation, and often reveals inequities in access to resources and issues related to privilege, power, and control (APA, 2021).

Summer Camp as a Developmentally Enriching Experience

Camp-aged youth exist in a prime window of life for “positive, life-altering development” (NASEM, 2019). Specifically, they are in the perfect time of their life to participate in enriching experiences that support development of important skills for adulthood, such as self-regulation, positive mindsets, values, and agency (Nagaoka et al., 2015). While youth development is an ongoing process that will occur with or without participating in enriching experiences, youth can be supported to “formulate and internalize the developmental ‘lessons’ from these experiences” (Nagaoka et al., 2015).

Research has consistently recognized summer camp as a setting that promotes social-emotional learning and character development (e.g., Richmond et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2019), which demonstrates that summer camp is a context for developmentally enriching experiences (Bialeschki et al., 2007; Thurber et al., 2007).

Opportunity Gap

A significant number of today’s youth do not have their developmental needs met. For example, living in poverty greatly increases the number of obstacles to participation in developmentally enriching experiences (Masten, 2000). This includes access to activities such as arts, music, sports, theatre, and other types of nonacademic activities — like summer camp.

Research has demonstrated that the opportunity gap persists during the summer months when more affluent youth are engaging in enriching experiences at higher rates than their lower-income peers (McCombs et al., 2017). More specifically, as access is highly dependent upon family income, and higher-income families are simply able to spend more on these experiences, this gap in spending between families of different socioeconomic status contributes to the widening of the opportunity gap.

Summer camp has proven to be a setting that provides developmentally enriching experiences (Bialeschki et al., 2007); however, average demographic statistics reported by ACA (2020) expose a gap of opportunity to participate in summer camp for marginalized youth: 65 percent of day campers and 68 percent of overnight campers attending ACA-accredited camps were white, and between 76 percent of day campers and 79 percent of overnight campers come from middle- and high-income households.

Constraints to Summer Camp

To understand how families experience constraints to summer camp, we investigated already existing research on accessing leisure activities. In this body of work, factors that impact access to leisure activities are called constraints. Constraints are categorized in three ways:

| Constraint Type | What this might look like when accessing camp | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Psychological |

|

| 2. | Social |

|

| 3. | Structural |

|

The most important thing we learned from the leisure research is that constraints do not necessarily prevent participation in leisure activities (Jackson et al., 1993). Research has shown that individuals use different strategies to negotiate, or navigate, and potentially overcome these constraining factors (Crawford et al., 1991). Leisure researchers created a visual model (i.e., the Leisure Constraint Negotiation Model; Crawford et al., 1991; Crawford & Godbey, 1987; Henderson et al., 1988; Jackson, 1990) for how individuals experience and navigate constraints in order to participate in leisure activities. This model provided a great foundation for us to conceptualize how families experience and navigate constraints when accessing summer camp programs.

A Model for How Families Navigate Constraints to Summer Camp

When thinking about constraints to summer camp attendance, we realized a summer camp-specific model would need to account for two parties (a parent or caregiver and a child) involved in experiencing both unique and familial constraints. The goal, of course, would be to participate in a developmentally enriching camp experience, rather than a leisure activity (e.g., playing golf).

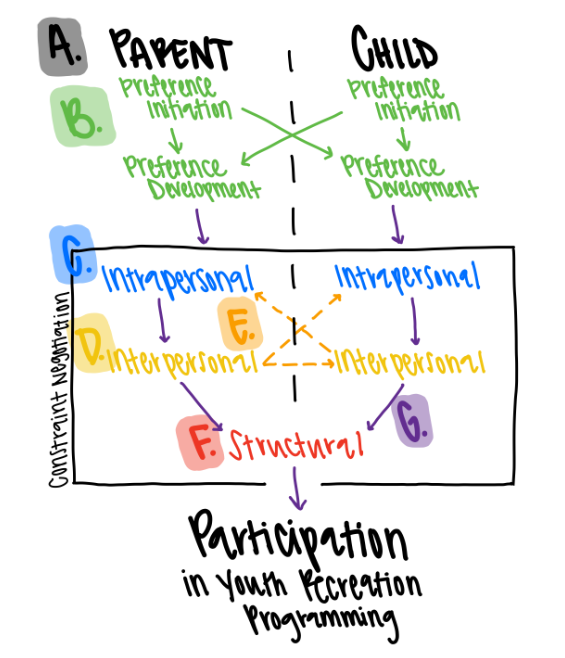

To create a model with these considerations in mind, we took what we knew about leisure constraint negotiation and revised it to fit what we expected to be different for families accessing summer camp. Then, we conducted semistructured interviews with families who were familiar with the experience of negotiating constraints. Based on what we learned from these interviews, we further refined the model, shown in Figure 1.

Let’s briefly walk through each component of the model. Refer to the corresponding letter in Figure 1 to follow along!

- Parent/Caregiver and Child. This model uses one parent or caregiver and one child to represent a family that has the goal of participating in summer camp programming.

- Preference Initiation and Development. To begin experiencing and negotiating constraints, families must first have a preference for, or interest in, summer camp, or decide that their goal is to participate in camp. Interest is often initiated in one party (e.g., a camp counselor comes to the child’s school to promote camp, or a parent’s friend raves about the impact camp had on their child), and then it is up to that party to convince the other party. Once the family decides that summer camp is their goal, they move through the model and begin experiencing constraints.

- Psychological (or Intrapersonal) Constraints. Both parents/caregivers and children experience this type of constraint, but they look different for each. (Refer to the Constraint Type table previously discussed for examples of these constraints.)

- Social (or Interpersonal) Constraints. These constraints pertain to interpersonal interactions and relationships between individuals’ characteristics; pretty much anything that has to do with other people. (Refer back to the Constraint Type table for examples of these constraints.)

- Interaction of Parent/Caregiver and Child Constraints. Through our interviews, we found that parents and caregivers are sometimes concerned about their child’s psychological constraints (e.g., if their child would be interested in the programming) and their child’s social constraints (e.g., if their child would make friends at camp). These constraints live within the parent/caregiver but affect the child as an individual in the model. We also found that children are sometimes concerned about their parent/caregiver (e.g., the health of their parent/caregiver while they are at camp). These constraints live within the child but affect the parent/caregiver as an individual within the model. This interaction is signified by the dashed orange arrows in the model.

- Structural Constraints. These constraints include the cost of camp, transportation to camp, if camp fits into their family summer schedule, and precamp preparation (e.g., paperwork and physician check-ins). They impact both family members to the same degree.

- Motivation. Motivation is what drives the family through the model, fuels the negotiation of constraints, and leads to participation. This is represented by the purple arrows in the model.

Depending on the family’s ability to negotiate their constraints, they will participate in summer camp programming in some capacity.

The next article in this series will further discuss constraint negotiation, as well as the ways in which culture may affect and shape constraints and the strategies one uses to navigate them.

Jessie Dickerson, MS, is a recent graduate from the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program at the University of Utah and is the project manager for ACA’s Camp Program Quality Initiative.

Taylor M. Wycoff, MS candidate in the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program at the University of Utah, is a research assistant for ACA.

References

- American Camp Association. (2020). Sites, Facilities, and Programs Report. Martinsville, IN: American Camp Association.

- Bialeschki, M. D., Henderson, K. A., & James, P. A. (2007). Camp experiences and developmental outcomes for youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 16(4), 769–788, vi.

- Carter, P. L. & Welner, K. G. (Eds.). (2013). Closing the opportunity gap: What America must do to give all children an even chance. Oxford University Press.

- Constraint. (2011). In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved from merriam-webster.com/dictionary/constraint

- Crawford, D. W., & Godbey, G. (1987). Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leisure Sciences, 9(2), 119–127.

- Crawford, D. W., Jackson, E. L., & Godbey, G. (1991). A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 13, 309-320.

- Henderson, K. A., Bialeschki, M. D., Shaw, S. M., & Freysinger, V. J. (1996). Both Gains and Gaps: Feminist Perspectives on Women’s Leisure. Venture Publishing Inc.

- Henderson, K. A., Stalnaker, D., & Taylor, G. (1988). The Relationship between Barriers to Recreation and Gender-Role Personality Traits for Women. Journal of Leisure Research, 20(1), 69–80.

- Jackson, E. L. (1990). Variations in the desire to begin a leisure activity: Evidence of antecedent constraints? Journal of Leisure Research. tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00222216.1990.11969814?

- needAccess=true

- Jackson, E. L., Crawford, D. & Godbey, G. (1993). Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 15(1), 1–11.

- Masten, A. S. (2000). Children who overcome adversity to succeed in life: Resilient Communities. In Just in Time Research: Resilient Communities (pp. 33-41). University of Minnesota. Retrieved from moodwatchers.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Children-Who-Overcome-Adversity-to-Succeed-in-Life.pdf

- McCombs, J., Whitaker, A., & Yoo, P. (2017). The Value of Out-of-School Time Programs. RAND Corporation. rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE267/RAND_PE267.pdf

- Mooney, T. (2018). Why We Say “Opportunity Gap” Instead of “Achievement Gap”. Teach For America. teachforamerica.org/stories/why-we-say-opportunity-gap-instead-of-achievement-gap

- Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., & Heath, R. D. (2015). Foundations for young adult success: A developmental framework. Concept paper for research and practice. University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. eric.ed.gov/?id=ED559970

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2019). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. (M.-J. Sepúlveda & R. Hutton, Eds.). The National Academies Press.

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2020). Achievement Gaps. National Center for Education Statistics. nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/studies/gaps/

- Richmond, D., Wilson, C., & Sibthorp, J. (2019). Understanding the role of summer camps in the learning landscape: An exploratory sequential study. Journal of Youth Development, 14(3), 9-30.

- Socioeconomic status. (2021). In apa.org. Retrieved from apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status

- Thurber, C. A., Scanlin, M. M., Scheuler, L., & Henderson, K.A. (2007). Youth development outcomes of the camp experience: Evidence for multidimensional growth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(3), 241–254.

- Wilson, C., Akiva, T., Sibthorp, J., & Browne, L. (2019). Fostering distinct and transferable learning via summer camp. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 269-277.