Mentors come in all types, shapes, and sizes. There are loud ones, quiet ones; short ones, tall ones; young ones, old ones.

The common denominator is “one” — as in “Be one!” While there are many things each of us cannot do, there is one thing we must do: mentor our youth.

Mentoring Defined

For sure, we all may describe “mentoring” somewhat differently. An article published by Health Services Research poses some relevant questions: “Although mentoring is something most of us talk about doing and needing on a regular basis, it isn’t obvious what being a mentor means, precisely, or what the process of mentoring entails. Is it the same as training? Teaching? Advising? Is being a mentor the same as being a good role model? Are these all labels for the same thing?” (McLaughlin, 2010)

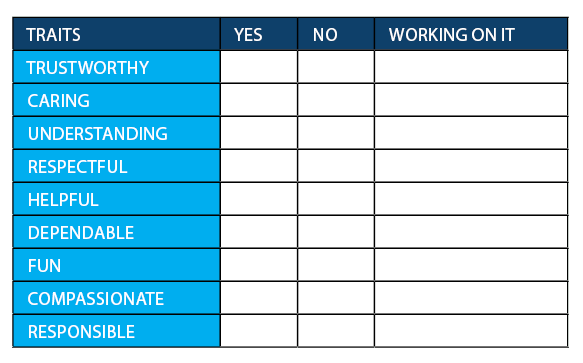

Perhaps an easier route is to define, or identify, the traits young people ascribe to those they consider to be their mentors. According to more than 3,000 youth surveyed, mentors are trustworthy, caring, understanding, respectful, helpful, dependable, fun, compassionate, and responsible (Wallace, 2008). So, do these attributes apply to you?

How to Be a Mentor — and Why It Matters

An article in Houston Family Magazine, “Need a Mentor? Go to Camp!” crystallizes the importance of your role as a counselor and offers tips on how to be good at it.

The idea of a mentor is an ancient one. In Greek mythology, when Odysseus, King of Ithaca, went to battle in the Trojan War, he placed his friend, Mentor, in charge of his son and his kingdom. Today, Mentor has become synonymous with someone who imparts wisdom to and shares knowledge with a less experienced person. Mentoring relationships are special and often life-changing.

The camp experience is uniquely designed to foster these relationships. When counselors and camp staff engage with campers, they are not just teaching — they are using the core elements of positive mentoring relationships.

- Camp counselors share and teach through stories and anecdotes. They impart wisdom from their own successes and failures, and offer the insight that comes from experience.

- Camp counselors model appropriate behaviors. They show campers how to play fairly, show empathy, and win and lose gracefully.

- Camp counselors guide campers through the learning landscape of life. They teach the things that cannot be taught in school — how to live with others, how to build friendships, how to lead, and how to work as a team.

- Camp counselors support campers emotionally. They offer reassurance when situations become difficult or overwhelming. Counselors are there to not only lend a hand but to help campers work through difficult moments and feel the sense of accomplishment that comes from conquering obstacles.

These relationships aren’t just a nice addition to childhood and young adult development; they are essential elements. Children need nurturing mentors, people outside of their families who take an interest in who they are, root for their successes, and help them learn that failures are critical stepping-stones on the path to success (Wallace, 2020).

Outcomes of Mentoring

The Psychology Today piece “An Invisible Thread” offers insight into the fruits of your labor.

Studies of “formal” mentoring, such as the kind found in Big Brothers Big Sisters programs, show that there is significant value in such relationships and universally point to the positive outcomes they engender. According to “Mentoring Programs and Youth Development: A Synthesis” from the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, “warm and close relationships with caring adults, supervision, and positive role models are the common resources and investments that mentoring interventions contribute to youth development.”

Similarly, a study by Child Trends found that youth participating in mentoring relationships experience better academic returns, hold more positive attitudes about the future, and are less likely to initiate drug use than those who aren’t.

Even “informal” mentors — such as school teachers, coaches, and counselors — hold considerable sway in the young lives they help to mold. According to research from SADD (Students Against Destructive Decisions), 46 percent of teens with a mentor reported a high “sense of self,” versus 25 percent of teens without a mentor. High sense-of-self teens feel more positive about their own identity, growing independence, and relationships with peers than do teens with a low sense of self (Wallace, 2013).

Book Smart

Three recent books can also inform your work as a mentor.

Tom Rath’s It’s Not About You suggests reframing “meaningful lives” by doing your best for others — in this case, your campers. This is a critical perspective as you transition from working on yourself through education and experience to making children, however temporarily, the center of your universe. It is at camp that you will have the opportunity to become one of three caring adults, other than parents, who children need to maximize their potential, according to the Search Institute. It refers to these connections as “Developmental Relationships.”

The Search Institute says, “Relationships are critical to young people’s development. They are also ‘active ingredients’ in schools, programs, and other critical services that have an impact on young people’s lives.” These are, it submits, “trustworthy, purposeful relationships that help young people . . .

- Discover who they are;

- Cultivate the abilities needed for them to shape their own lives; and

- Learn how to engage with and contribute to the world around them” (Search Institute, 2020).

As my camp director used to say, “You will never do more important work” than that of a camp counselor. This, too, can spark a change in perspective, or mindset, from “I have to” to “I get to.”

Equally significant is a book by Daniel J. Siegel, MD, and Tina Payne Bryson, PhD, The Power of Showing Up. Indeed, being “present” in the lives of your campers is a particularly powerful concept. Siegel and Bryson say, “Showing up means offering a quality of presence. And it’s simple to provide once you understand the four building blocks of a child’s healthy development . . .” (Monke, 2020).

They argue that every child needs to feel the following (Siegel and Payne Bryson, 2020):

- Safe: We can’t always insulate children from injury or avoid doing something that leads to hurt feelings. But when we give children a sense of safe harbor, they will be able to take the needed risks for growth and change.

- Seen: Truly seeing children means we pay attention to their emotions — both positive and negative — and strive to attune to what’s happening in their minds beneath their behavior.

- Soothed: Soothing isn’t about providing a life of ease; it’s about teaching children how to cope when life gets hard and showing them that you’ll be there with them along the way. Soothed children know that they’ll never have to suffer alone.

- Secure: When children know they can count on you, time and again, to show up — when you reliably provide safety, focus on seeing them, and soothe them in times of need, they will trust in a feeling of secure attachment. And thrive!

Similar themes can be found in an essay written by psychologist Debbie Hall for NPR (Hall, 2005).

Presence is a noun, not a verb; it is a state of being, not doing. States of being are not highly valued in a culture which places a high priority on doing. Yet, true presence or ‘being with’ another person carries with it a silent power — to bear witness to a passage, to help carry an emotional burden, or to begin a healing process. In it, there is an intimate connection with another that is perhaps too seldom felt in a society that strives for ever-faster “connectivity.”

With therapy clients, I am still pulled by the need to do more than be, yet repeatedly struck by the healing power of connection created by being fully there in the quiet understanding of another. In it, none of us are truly alone.

The power of presence is not a one-way street, not only something we give to others. It always changes me, and always for the better.

Finally, Kate Murphy’s You’re Not Listening — What You’re Missing and Why It Matters, reminds us of the imperative of practicing “active listening.” How do you do that? MindTools has some advice (2019):

There are three key active listening techniques you can use to help you become a more effective listener.

1. Pay Attention

Give the speaker your undivided attention and acknowledge the message. Recognize that nonverbal communication also “speaks” loudly.

- Look at the speaker directly.

- Put aside distracting thoughts.

- Don’t mentally prepare a rebuttal!

- Avoid being distracted by environmental factors. For example, side conversations.

- “Listen” to the speaker’s body language.

2. Show That You’re Listening

Use your own body language and gestures to show that you are engaged.

- Nod occasionally.

- Smile and use other facial expressions.

- Make sure that your posture is open and interested.

- Encourage the speaker to continue with small verbal comments like, yes, and “uh huh.”

3. Provide Feedback

Our personal filters, assumptions, judgments, and beliefs can distort what we hear. As a listener, your role is to understand what is being said. This may require you to reflect on what is being said and to ask questions.

- Reflect on what has been said by paraphrasing. “What I’m hearing is . . .” and “Sounds like you are saying . . .” are great ways to reflect.

- Ask questions to clarify certain points. “What do you mean when you say . . .” “Is this what you mean?”

- Summarize the speaker’s comments periodically.

At the End of the Day

Truth be told, at the end of the proverbial day, for all the great advice out there to help you find success as a camp counselor, your best guide may, in fact, be yourself. On that point, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “My imagination, my love and reverence and admiration, my sense of miraculous, is not so excited by any event as by the remembrance of my youth.”

Remembering your own childhood experiences can be an invaluable guide to working with children. Ask yourself these questions, calibrated by the age of the campers you will lead:

- What fears did you have?

- How did you feel about being — or sleeping — away from home?

- What activities did you enjoy the most?

- What activities did you enjoy the least?

- Who were the most important people in your life?

- What made you laugh?

- What made you cry?

- What were you insecure about?

- What were your favorite possessions?

- Who helped you to feel safe, loved, and taken care of?

That last one is reminiscent of the charge of a camp orientation speaker Lonnie Carton, PhD, to “help make children feel lovable and capable,” something I refer to as “The Main Thing” in my book, IMPACT — An Introduction to Counseling, Mentoring and Youth Development.

Relational vs. Transactional Counseling

Connecting with your campers on an emotional level, letting them know you care about them as people, leading with love, and being “accessible” in terms of your own experiences, struggles, and feelings (as appropriate and in keeping with your camp’s guidelines for your work), is a powerful way to positively influence youth. Counselors who focus primarily on the logistics of the job — keeping schedules and ensuring campers make it to meals and brush their teeth before bed — miss out on important opportunities to teach within and about relationships.

Unconditional personal support can go a long way toward fulfilling the promise of camp as a game changer in the grand scheme of healthy youth development.

That is what makes for a different kind of mentor. What kind will you be?

References

- Education Revolution. (2020). Relational learning . . . say what? Alternative Education Resource Organization. Retrieved from educationrevolution.org/blog/relational-learning-say-what/

- Hall, D. (2005, December 26). The power of presence. This I Believe. Retrieved from npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5064534

- Houston Family. (2019, January 17). Need a mentor? Go to camp! Houston Family Magazine. Retrieved from houstonfamilymagazine.com/family-feed/need-a-mentor-go-to-camp/

- McLaughlin C. (2010). Mentoring: What is it? How do we do it and how do we get more of it? Health Services Research, 45(3), 871–884.

- Mind Tools. (2019). Active listening: Hear what people are really saying. Retrieved from mindtools.com/CommSkll/ActiveListening.htm

- Monke, A. (2020, January 3). The power of showing up. Sunshine Parenting. Retrieved from sunshine-parenting.com/ep-121-the-power-of-showing-up/?cl_subscriber-id=195848913

- Murphy, K. (2020). You’re not listening: What you’re missing and why it matters. New York, NY: Celadon Books.

- Rath, T. (2019, December 26). It’s not about you: A brief guide to a meaningful life. Amazon Original Stories. Retrieved from tomrath.org/book/its-not-about-you-a-brief-guide-to-a-meaningful-life/

- RYOT Studio. (2019, July 15). Shifting your mindset from “I have to” to “I get to”. HuffPost. Retrieved from huffpost.com/entry/shifting-your-mindset-from-i-have-to-to-i-get-=to_n_5d14fd4ae4b03d6116385558?

Stephen Gray Wallace, MS Ed, is president/director of the Center for Adolescent Research and Education (CARE), a national collaborative of institutions and organizations committed to increasing favorable youth outcomes and reducing risk. He is a consultant to camps on staff training, teen leadership programming, and outcomes measurement, and has broad experience as a camp director, school psychologist and adolescent/family counselor. Stephen is a member of the professional development faculty at the American Academy of Family Physicians and American Camp Association and a parenting expert at kidsinthehouse.com, NBC News Learn, and WebMD. He is also an expert partner at RANE (Risk Assistance Network & Exchange) and was national chairman and chief executive officer at SADD for more than 15 years. Stephen is author of the books, Reality Gap and IMPACT. Additional information about Stephen’s work can be found at StephenGrayWallace.com.

© Summit Communications Management Corporation 2020. All Rights Reserved.