In 2008, over 20 camp researchers gathered for the American Camp Association (ACA) Research Collaborations Summit where they identified areas of future research, which included this question: How do camps contribute to the development of caring and competent citizens, their communities, and the environment? This question aligns with research from other fields that raises the concern that Americans are less connected to society and each other than in the recent past (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 2008; Putnum, 2000). Scholars agree that if we are to address this growing disconnect, we need to foster civic skills and commitment to civic engagement in youth to encourage lifelong civic participation (Melaville, Berg, and Blank, 2006; Newton, 1975; Obradovic & Masten, 2007; Sherrod, Flanagan, and Youniss, 2002; Wray-Lake & Syvertsen, 2011).

Research on summer camp programming has demonstrated that camps can engender many of the same skills and competencies as other youth programs that work to promote civic skills (American Camp Association, 2005; Bialeschki, Lyons, & Ewing, 2005; Garst, Browne, Bialeschki, 2011; Thurber, Scanlin, Scheuler, & Henderson, 2007). Despite these similarities, summer camp is not widely recognized as a context for civic development, despite evidence suggesting that camp is an ideal context for this goal (Browne et al., 2011; Devine & Parr, 2008; Yuen, Pedlar, & Mannell, 2005). Well known, however, are the ways intentionally designed structured curricula can be effective mechanisms for targeting specific outcomes (Arend & Rogers, 2012; Browne & Sibthorp, 2012; Browne et al., 2011; Garst & White, 2012; Roark & Evans, 2010). There is a need to better understand how curricula intentionally designed to foster civic outcomes in a summer camp setting fosters civic development among campers. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the Teens Leading & Connecting (TLC) program, a structured camp curriculum designed to impact campers’ civic skills and civic engagement, to provide insight into how a structured curriculum might impact campers’ civic engagement in their home communities.

The Teens Leading & Connecting Program

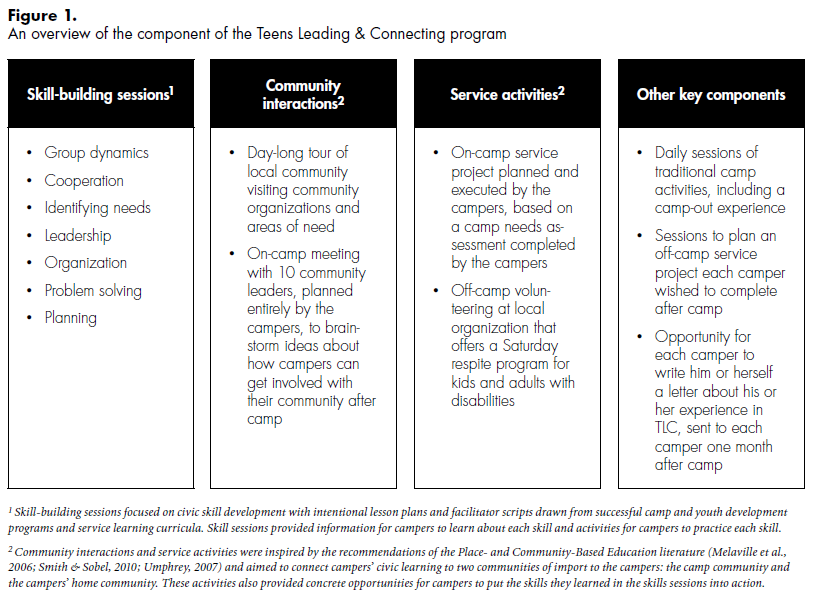

The TLC program was implemented at a YMCA day camp in northwest Georgia for one week in the summer of 2012 with 10 campers aged 13-16. See Figure 1 for an overview of the main components of TLC.

Methods

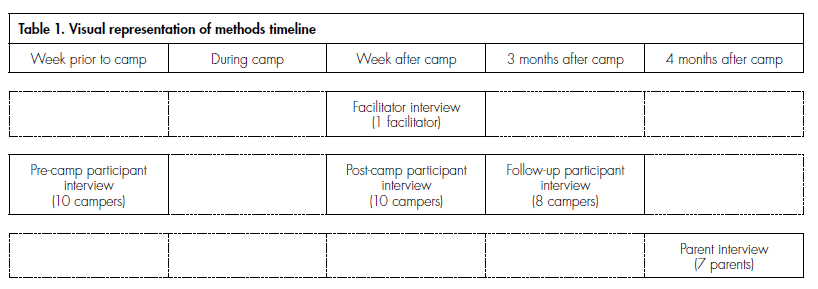

The qualitative methods are displayed in Table 1. First, the researcher interviewed each TLC camper before (pre-camp ideas about community and levels of engagement), one week after (civic skills, attitudes, and motivations gained in TLC), and three months after TLC (retention and application of civic skills, attitudes, and motivations). Second, the researcher interviewed the TLC facilitator about his experience implementing the program. Third, the researcher interviewed one parent of each camper to understand parents’ perceptions of campers’ gains.

As recommended by Hycner (1985), after transcription and multiple readings of the interviews, the researcher identified ideas (individual quotes) within each interview, clustered the ideas into like groups in each interview, labeled the like groups within each interview with theme names that described those ideas, clustered like idea groups from all the interviews together, then labeled the like groups from all the interviews with theme names that described those ideas.

Findings

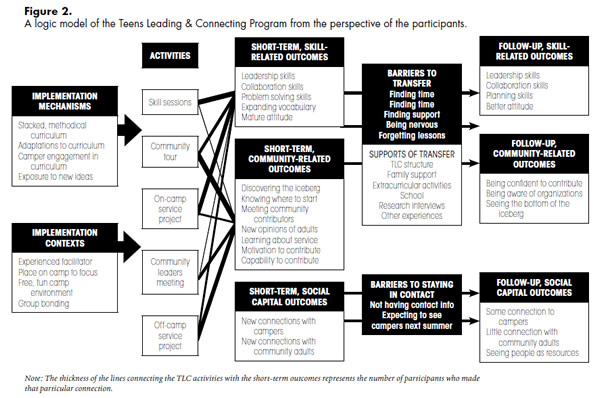

The themes from all interviews were compiled to create a logic model of the TLC program from the perspective of the participants (campers, facilitator, and parents). See Figure 2. At the far left of the logic model are the mechanisms and contexts the participants described as important to the successful implementation of TLC. To the right are the activities of TLC linked to the post-camp outcomes campers reported. Finally, on the far right are the follow-up outcomes campers and parents identified, connected to the short-term outcomes via the supports of and barriers to transfer identified by the participants.

Beyond the logic model, one further theme should be noted. Five campers and one parent argued that TLC was “more than camp” and possessed a purpose beyond a traditional camp. Amanda said, “I feel like [at] camp you just have fun and eat and you don’t really learn anything. It’s just like play time. Fun. And in TLC, you feel like you actually got something done.” Further, Dustin’s father stated, “Dustin felt he was part of something special. It wasn’t just another week at camp. There was actually a purpose.”

Campers also discussed that TLC offered activities beyond traditional camp. For example, Shakur expressed, “ . . . I guess [TLC] was a little more than [camp] because we like left and we helped the community and stuff.” Finally, in addition to being more than camp, Stevie also compared TLC to school. She argued:

And then [TLC is] also like school ’cause you’re learning and writing about all this stuff. But then you realize this is nothing like school because school is . . . boring. This like actually gives you time to do projects and like think about what you just learned. Unlike school ’cause they just rush you.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the Teens Leading & Connecting program to investigate how a structured camp curriculum might foster civic outcomes in campers. The findings indicate that TLC fostered civic skills and motivation in campers and several of these gains were retained three months after camp. TLC fostered in campers an awareness of the needs of their community, the organizations in their community, and their own ability to contribute to the community. Though these gains did not always result in increased active civic engagement after TLC due to campers’ time and support barriers outside of camp, both campers and parents felt that the campers’ new awareness and confidence to contribute was an important avenue through which campers engaged with society. Gruenewald and Smith (2008) argued that for youth to become civically engaged, they must develop a “readiness for social action”. TLC seemed to foster this readiness in the campers. Campers felt that factors like the structure of the program itself, family support, extracurricular and school activity involvement, and the research interviews supported their retention of this readiness after camp.

Further, participants were able to verbalize how the TLC program worked for them. For participants, TLC had a clear purpose that they were able to identify. As Browne and colleagues (2011) explained, structured curricula “. . . allow camps to target desired outcomes and document their efforts to stakeholders.” The findings of this study suggest that the use of a structured curriculum seemed to make programming more transparent for participants. For example, scripts for skill sessions in TLC included purposeful language that discussed the intended targeted skills of individual activities and larger skill sessions. Further, the TLC facilitator was instructed to relate each skill session to the campers’ home community to remind campers of the ultimate purposes of TLC. Roark, Gillard, Evans, Wells, and Blauer (2012) discussed the importance of embedding the language of intended outcomes into intentional programming scripts to help facilitate intended outcomes. Garst and White (2012) talked about the benefits of explicitly labeling desired outcomes for participants to avoid what they term “the pitfalls of happenstance.” In doing so, participants become aware of the intended purposes and outcomes of an intentional program (Roark et al., 2012). TLC aimed to achieve such embedding and the findings of this study suggest that these intentions transferred to the participants.

Finally, the findings of this study suggest that a structured curriculum was not the norm for the TLC campers. While most concluded they preferred the TLC structure, in dubbing the program as “more than camp,” campers seemed not to fully associate the TLC experience with the typical camp experience. Campers did not always associate traditional camp with learning like they described with TLC. Many times, the learning that takes place at camp happens organically, through traditional programming and even unstructured time. Garst and colleagues (2011) stated, “It is possible that unstructured time, particularly when it is used intentionally to foster positive outcomes, is a unique way camps effectively promote positive youth development.” Consequently, there is a need to find balance between the developmental benefits of structured camp curriculum and the freedom and fun so inherent to the camp experience.

Authors’ Note: The authors thank Barry Garst, Deb Jordan, Sandy Linder, and Fran McGuire for their input into this project. Also, thanks to the camp director and staff members of the hosting day camp who made this study possible.

References

American Camp Association. (2005). Directions: Youth development outcomes of the camp experience. Retrieved from www.ACAcamps.org/ research/enhance/directions American Camp Association. (2008). Camp research collaboration summit summary. Retrieved fromwww.ACAcamps.org/research/ connect/collaborations-summit Arend, L., & Rogers, M. (2012, February). A utilization-focused evaluation of a pilot reading program at Sherwood Forest Camp, Presentation conducted at the American Camp Association National Conference, Atlanta, GA. Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (2008). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Original work published in 1985.) Bialeschki, D., Lyons, K., & Ewing, D. (2005). Youths’ perspectives on camp outcomes: Intentionality and positive youth development. Twelfth Canadian Conference on Leisure Research. Vancouver, Canada. Browne, L., Garst, B., & Bialeschki, D. (2011). Engaging youth in environmental sustainability: Impact of the Camp 2 Grow program. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 29(3), 70-85. Browne, L., & Sibthorp, J. (2012, February). Fostering camp connectedness through structured curricula at day camp, Presentation conducted at the American Camp Association National Conference, Atlanta, GA. Devine, M. A., & Parr, M. G. (2008). “Come in, but not too far: Social capital in an inclusive camp setting.” Leisure Sciences, 30, 391-408. Garst, B. A., Browne, L. P., & Bialeschki, M. D. (2011). Youth development and the camp experience. New Directions for Youth Development, 130, 73-87. Garst, B. A., & White, C. P. (2012). Leadership and environmental stewardship: A curriculum for camps and other youth programs. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning. Gruenewald, D. A., & Smith, G. A. (2008). Introduction: Making room for the local. In D. A. Gruenewald, & G. A. Smith (Eds.), Placebased education in the global age (pp. xiii-xxiii). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Hycner, R. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8, 279-303. Melaville, A., Berg, A. C., & Blank, M. J. (2006). Community-based learning: Engaging students for success and citizenship. Retrieved from: www.communityschools.org/assets/1/AssetManager/CBLFinal.pdf Newton, F. M. (1975). Education for citizen action: Challenge for secondary curriculum. Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publishing. Obradovic, J., & Masten, A. S. (2007). Developmental antecedents of young adult civic engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 11(1), 2-19. Roark, M., & Evans, F. Play it, measure it: Experiences designed to elicit specific youth outcomes. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning. Roark, M. F., Gillard, A., Evans, F., Wells, M. S., & Blauer, M. M. (2012). Effect of intentional designed experiences on friendship skills of youth: An application of symbolic interaction theory. Journal of Parks and Recreation Administration, 30(3), 24-36. Sherrod, L. R., Flanagan, C., & Youniss, J. (2002). Dimensions of citizenship and opportunities for youth development: The what, why, when, where, and who of citizenship development. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 264-272. Smith, G., & Sobel, D. (2010). Place- and community-based education in schools. New York, NY: Routledge. Thurber, C., Scanlin, M., Scheuler, L., & Henderson, K. (2007). Youth development outcomes of the camp experience: Evidence for multidimensional growth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 241-254. Umphrey, M. (2007). The power of communitycentered education: Teaching as a craft of place. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Wray-Lake, L., & Syvertsen, A. K. (2011). The developmental roots of social responsibility in childhood and adolescence. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 134, 11–25. Yuen, F. C., Pedlar, A., & Mannell, R. C. (2005). Building community and social capital through children’s leisure in the context of an international camp. Journal of Leisure Research, 37, 494-518.

Tracy Mainieri is an assistant professor at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois. Her research focuses on program evaluation, summer camp, civic engagement, and social capital. Tracy can be reached at [email protected].

Denise Anderson is an associate professor at Clemson University in the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management.

Published in the 2015 March/April Camping Magazine.