Agency is the ability to act as an effective agent for yourself — getting your mind, body, and emotions in balance to think clearly and make choices that improve your life.

Simply put, agency is what we all use to feel in command of our lives.

Recall the last time you made an important decision. Perhaps you set time aside to research your options and calmed yourself before making a choice. Maybe you went for a run to clear your head or slept on it, knowing that rushing into a decision could lead to a bad choice. When you help your campers advocate for themselves (find their voices), you help them build agency.

When you are empathetic, collaborative, and open to learning at work, you are using your personal agency. We all have the potential to develop greater agency in our lives. We’re born with this capacity, but building it requires keeping a steady hand on the tiller of our minds and bodies — allowing us to behave and think in new ways. Through doing so we can lead others and ourselves thoughtfully and with fewer mistakes or undesirable outcomes.

Unfortunately, we see much evidence that people’s agency has declined in recent years to the point it is under serious threat. Repercussions from this decline increasingly show up in the camp setting. Campers arrive very stressed out, their parents are more worried about them, and camp staff are grappling with more personal issues. Fortunately, the camp experience offers much to correct this.

Eroding Agency — Our Youth Are the Most Vulnerable

Living in a fast-paced, digital society takes a heavy toll on people. Most of us struggle to adapt to the rapid changes taking place around us. When anxious and stressed out, we lose access to our agency. According to data from the World Health Organization, America ranks as one of the most anxious nations on earth (Kessler, et al., 2007), with nearly one in five adults — a full 40 million Americans — currently diagnosed with a mental health disorder, of which anxiety is the most common (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.; American Psychological Association, n.d.). Many more people hover just below the clinical diagnosis, absorbing and carrying around unhealthy amounts of tension, worry, and fear, which create more distraction, restlessness, and fatigue. We struggle to keep clear minds and to think for ourselves, limiting our ability to make the best decisions in our lives.

Young people aren’t spared from the effects of living amidst this mostly silent national epidemic of anxiety. Always-on technology and an increased focus on metrics and performance are part of their everyday lives, leaving youth frequently overwhelmed. According to one study, the average school age child today has more baseline anxiety than a child psychiatric patient of the 1950s (Twenge, 2000). Teens and young adults appear to be the most affected. The American Psychological Association’s Stress in America Survey (2018) found that 90 percent of 15- to 21-year-olds reported being “stressed out” (Plante, 2018). In 2017, researcher Jean Twenge, writing in The Atlantic, described iGens (the generation growing up with smartphones) as “being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades.”

Agency Boosts Confidence, Lowers Anxiety

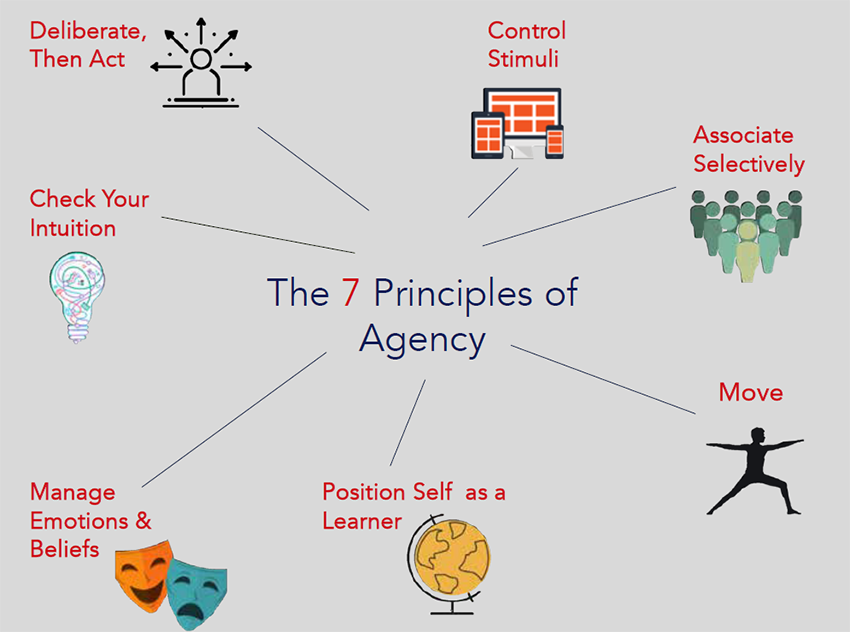

In our consulting and clinical work, we discovered that confidence gained through higher levels of personal agency fends off anxiety and the sense of being overwhelmed. From interviews and assessments with a diverse range of people across the country, we discovered that practicing seven distinct principles was key to how these individuals developed agency in their lives.

The Seven Principles That Build Agency

We point out to teachers, counselors, and parents that they are, in effect, modeling agency to those in their charge. We advise camp staff to develop their own personal agency before they seek to model or teach the agency principles to campers. How to start? Make certain you are calm, clear-headed, and using a reasonable framework to make your decisions. Here’s how:

- Control stimuli.

- Associate selectively.

- Move.

- Position yourself as a learner.

- Manage your emotions and beliefs.

- Check your intuition.

- Deliberate, then act.

A further delving into each principle follows.

Control Stimuli

Agency begins with what you let into your mind — meaning what comes in from your environment. If you lack agency, you’ve likely allowed your attention to be hijacked, and you need to figure out how to restore it.

Cut back on the number of distractions, mainly through shutting down digital devices. This will increase your ability to more thoughtfully choose where your attention goes. This improves your level of concentration, bolsters creative thinking, and makes you less susceptible to impulsive acts and poorly thought-through decisions.

At camp, consider if you are managing all forms of stimulation. Are you overloading campers with high-energy activities? Are too many choices overwhelming their decision-making? Make certain you build in opportunities throughout the day to slow the pace down — take breaks, rest, and engage in moments of calm reflection.

Associate Selectively

It’s impossible not to be affected by those around us. Like a virus, it’s easy to “catch” the emotions of others, as our brains tend to synch up when we associate with other people. Setting boundaries with difficult people is important. Disentangle yourself from negative interactions, and be more conscious of how you might be vulnerable to “groupthink” — social pressure to behave or think in ways that are contrary to your values.

Surrounding yourself with healthy, empathetic, open-minded, candid, and supportive people will boost your mood, elevate your motivation, and improve your overall health and well-being.

Consider the effects of how kids are grouped together at camp. Are these groupings healthy and building positive interactions? Arrange groups to lower unhealthy competition. At the same time, give kids some room to cluster organically and explore their relationships in less-structured, supervised ways.

Move

Physical movement, along with proper rest and nutrition, puts your body and mind into balance, giving you greater motivation, strength, and stamina. Research has shown that frequent sitting is dangerous to your health, and that even short breaks from concentrated periods of inactivity — like getting up to stretch or walking around the block — are good for you. Studies also suggest that exercise can lead to greater self-control — the ability to defer gratification, which is central to agency.

Focusing on movement, and on the nutrition and rest necessary to keep you active and in balance, increases mental, physical, and emotional strength and stamina — essential building blocks to all body and mind functions.

Frequent movement and exposure to nature is foundational at most camps. For overnight camps, sleep schedules are often more consistent than when children are at home. Introduce campers to new and fun ways to move their bodies. Encourage them to try new activities and take good risks. Watch for unvarying choices and for playing it too safe. Teach kids to listen to what their bodies are telling them. These signals can often be ignored or go unregistered. Am I hungry? Full? Am I feeling tired? Is my ankle sore? Are there butterflies in my stomach? Is my head feeling bad? Movement and exposure to nature at camp is a true gift for exercise-starved children. This couldn’t be more important. According to the Yale School of Forrest and Environmental Studies, “Parents of children 8 to 12 years old said that their children spend three times as many hours with computers and televisions each week as they do playing outside” (2017).

Position Yourself As A Learner

People with high levels of agency are continually learning more and expanding their capacity to learn. They do this by adopting a more open, collaborative approach to all experiences in life. This requires nurturing your curiosity and allowing yourself to explore new ideas, skills, and people.

It starts with actively questioning, listening, and creating moments of learning.

Positioning yourself as a learner at camp requires lowering your guard. Try to be less self-conscious and not worry about what others might be thinking about you. When you don’t know something, ask. Don’t be defensive, but model open-mindedness for your campers and colleagues by placing yourself in the role of a learner.

Manage Your Emotions And Beliefs

Too often we operate from unconscious beliefs (If I’m not going to be great at something, it’s not worth trying, or, I’m not ready to get close to people because they always take advantage of me) without being aware of how these beliefs thwart us from having new experiences that could change how we see the world and our place in it. When we are driven by unconscious emotions like fear, sadness, or worry, it can lower our energy and make us feel a sense of dread or overwhelmed, lowering our agency. When we are overly aggressive (because we believe that’s how to gain respect and self-worth), we likely push positive, supportive people away.

To improve this practice of agency, start by cultivating greater self-awareness. Increasing your awareness of how your emotions and beliefs drive your thinking, influence your behavior, and affect your judgment will help you navigate your life with greater confidence. Self-reflection helps you keep grounded and emotionally stable by slowing down your thinking process. This also helps to keep negative and disruptive emotions at bay.

Camps provide many great emotional experiences. People come together in new and healthy places to play, work, and explore new activities and parts of themselves. The opportunities for building agency are tremendous, but over recent years, camps have been reporting significant increases in anxiety (and depression) not only in campers and parents, but also in staff (Ditter, 2016).

When you or someone around you feels overwhelmed, enlist the first three behavioral principles to help regain emotional balance. These three principles get to the heart of what’s throwing us off balance and are easy to implement. Not coincidentally, these are the principles we recommend focusing on when you work with young children. By middle school, when cognitive development advances, the other principles come into play more.

Control stimuli:

- Get to a quiet, low-stimulation place.

- Breathe and meditate.

- Stay off social media and don’t text (reach out to people in face-to-face, in-the-flesh ways).

Associate selectively:

- Seek out calm and emotionally stable people whom you trust.

- Observe how they stay calm and adopt their mannerisms and behaviors.

Move:

- Don’t stay immobile when upset — it makes you feel more trapped in negativity.

- Get outdoors if possible.

- Assess sleep habits and nutrition and make positive changes.

- Check in and listen to what your body may need before strong emotions get set off and surface.

Check Your Intuition

Think of intuition as deep inner knowledge comprised of millions of data points that our brains have observed over the course of our lives. When used wisely (not impulsively), intuition can be a tremendous boost to our creativity and help us make better decisions, increasing our level of agency.

Increasing awareness of how your body is responding to new situations and people is a great place to start.

At camp, teach children to acknowledge their feelings. If they feel uncomfortable — experience tension in their muscles and their heart rate increases — these signals are worth paying attention to. They can guide campers to make decisions about whether to stay in situations or around people who, for whatever reason, may be causing this visceral intuitive reaction. Other types of intuition happen when we try to solve complex problems (finding our way through a wooded area or the steps that go into solving a computer programming challenge). Teach campers that as humans we often “feel” our way through uncertainty. For camp leaders and counselors, learning to trust and wisely let your inner wisdom guide you can be extremely helpful in reading what your campers need and how to respond empathically.

Deliberate, Then Act

People with low agency experience common impediments when trying to make sound decisions. They may procrastinate, obsess over details, or worry excessively during the process. They may lack confidence and be risk averse. Their thinking may be too fast, causing them to act on impulse.

When making high-stakes decisions, it’s helpful to stop and calmly deliberate first.

- Put yourself in an environment conducive to reflection and exploration, and make sure you have time and your emotions are calm.

- Focus on the issue at hand enough to clarify your primary objective and what is at stake.

- Ask open-ended questions and gather pertinent facts.

- Generate options, making sure no strong emotions or thinking biases are driving your decision-making.

- Draft a plan for yourself based on those options, putting your thoughts and decisions into writing. The plan should simplify your options and incorporate the most important facts.

- Let your mind rest and allow any intuitive thoughts to rise to the surface. Set your plan aside for a day.

- Reassess your plan, making changes as necessary.

Use this principle when campers (or you) are indecisive. Overthinking stops people from opening doors to new possibilities. Having agency — acting decisively and proving to yourself that you can handle whatever may come next — bolsters your confidence. Higher confidence means lower anxiety and fear. Remember, taking action doesn’t require 100-percent certainty. Higher-agency people will take action if they are 80 percent sure or more. So, don’t over-deliberate before acting; you can always reassess later if need be.

Having agency means taking responsibility for your life. The next time you sense something happening around you or within you that doesn’t feel quite right, don’t ignore it and reflexively press on. Exercise the discipline to stop, pay attention, and work on finding a better path on which to move forward. By developing agency, you’ll have more influence over your life and greater impact on the lives of others.

References

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Data on behavioral health in the United States. APA. Retrieved from apa.org/helpcenter/data-behavioral-health

- Ditter, B. (2016, September). Staff anxiety — The new normal. Camping Magazine. Retrieved from ACAcamps.org/resource-library/staffanxiety-new-normal

- Kessler, et al., (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-ofonset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6.3, 168–176.

- National Institute of Mental Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Mental illness. NIMH. Retrieved from nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml.

- Plante, T. G. (2018, December 3). Americans are stressed out, and it is getting worse. Psychology Today. Retrieved from psychologytoday.com/us/blog/do-theright-thing/201812/americans-are-stressed-out-and-itis-getting-worse

- Twenge, J. M. (2017, September). Have smartphones destroyed a generation? The Atlantic. Retrieved from theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-thesmartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/

- Twenge, J. M. (2000). The age of anxiety? Birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 1007–1021.

- Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. (2017, April 27). U.S. study shows widening disconnect with nature, and potential solutions. Yale Environment 360. Retrieved from e360.yale.edu/ digest/u-s-study-shows-widening-disconnect-withnature-and-potential-solutions

Anthony Rao, PhD, has been a staff psychologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and an instructor at Harvard Medical School. He’s the author of two books and is regularly an expert commentator in news segments on trends affecting children. Anthony is also a recipient of the ACA, New England Peter Kerns Award for the Advancement of Professional Development.

Paul Napper, PsyD, leads a management psychology practice in Boston. His client list includes Fortune 500 companies, nonprofits, universities, and start-ups, and he has held an advanced fellowship during a three-year academic appointment at Harvard Medical School. His latest book, The Power of Agency, explores strategies to lower anxiety through seven principles that promote human agency. For more information, visit PowerofAgency.com.

Photo courtesy of North Star Reach, Pinckney, Michigan.