Anyone who operated, worked at, or attended a camp this past summer knows more than a thing or two (and likely more than they ever wanted to know) about risk. I, Briana Mitchell, am one of those people.

After spending the greater portion of a year recruiting over 500 campers, this past July, in partnership with an incredible team — I founded a camp. This two-week, sleep-away camp served as the summer home to Black and brown children from the most urban centers within New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. Many of our campers had no previous sleep-away camp experience. Almost all of our campers had spent the greater portion of the last two academic years at home, learning remotely.

While in the many planning and preparation stages leading up to camp, I assessed risk from every angle that I could. I spent countless hours in meetings with our expanded health center team crafting protocols for worst-case scenarios to determine how to best prevent them. Our guiding principle was an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

For many of us whose camps ran programs this past summer, the accurate measure would be closer to a ton of prevention. We planned, strategized, hypothesized, and diagrammed every risky scenario we could conceptualize. At my camp, our “ton” of prevention materialized into a robust playbook that included many protocols — namely testing before camp, during camp, and prior to sending campers home to their families. Compared to some camps, this may have seemed excessive, but we felt testing was the best way to mitigate the risk of a positive COVID-19 case. And it worked. For six weeks. Hundreds of campers and counselors, multiple rounds of tests — all of them negative. We took an enormous risk launching a camp this summer, and if we were playing the board game, Risk, a boaster could proclaim that we’d won, right?

Perhaps, but a win doesn’t mean we rest on our laurels.

As many a camp director does, I would spend a portion of each program day in the health center. I checked in on campers, monitored intake logs for patterns, offered words of encouragement to the woebegone, and most frequently, oversaw the distribution of daily medicines.

One evening as I sat underneath the lanterns of the outdoor tent erected to keep medicine distribution outdoors, I asked my head nurse why the process took so long. When planning the daily schedule and accounting for med distribution, I factored in about 20 minutes. In contrast, successfully distributing all prescribed medicine to our campers took close to an hour. It baffled me. For clarity, I asked, “Are there really this many campers who take daily meds?”

My seasoned head nurse answered, “Most of the meds are asthma related.”

I sank down lower into the plastic folding chair and resigned myself to a sobering thought. While there was still a very palpable risk of the spread of COVID-19 at camp, being outside and engaging in good old-fashioned physical activity also posed a risk to some of my campers who had preexisting, severe asthma.

Asthma and Communities of Color

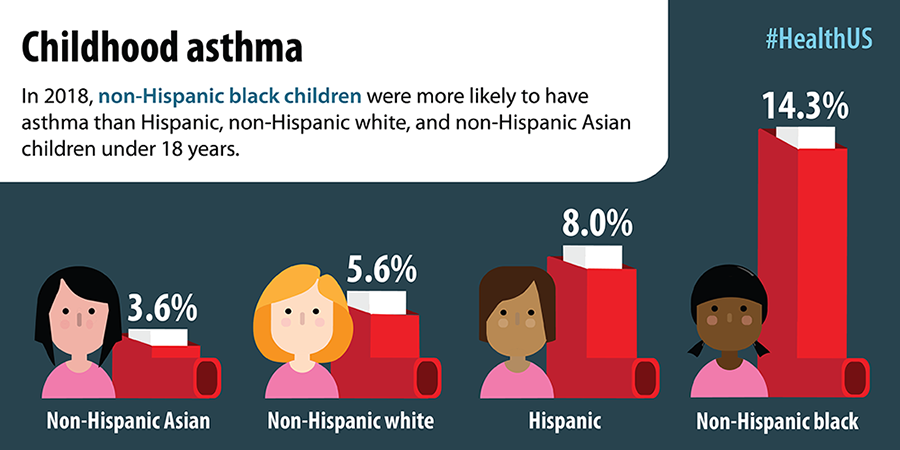

The incidence of asthma has increased dramatically in all segments of the United States population over the past 20 years. That being said, asthma is troublesome in urban populations and among racial/ethnic minority populations. In the US, the asthma hospitalization and morbidity rates for nonwhites are more than twice those for whites (Clark et al., 1999).

Researchers have long linked asthma — a serious and life-threatening chronic respiratory disease that affects the quality of life of more than 23 million Americans — with exposure to air pollution. Air pollution can make asthma symptoms worse and trigger asthma attacks. The estimated six million children in the US with asthma are especially vulnerable to air pollution.

While we do not know the exact causes of asthma, a variety of environmental factors can trigger attacks and worsen respiratory conditions. The primary outdoor factor is air pollution as particulates.

Dense automobile traffic, industrial emissions, bus depots, and waste storage facilities are large sources of air pollution that can worsen air quality. Unfortunately, those pollutants are predominantly in inner cities that are largely minority communities.

Results of a new study by Johns Hopkins researchers using national data adds to the evidence that living in inner cities can worsen asthma in children. This study also documents persistent racial/ethnic health disparities.

Image Source: CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics — Monitoring the Nation’s Health

The Space Race

Race is the most significant predictor of a person living near contaminated air, water, or soil. Such polluted locales have exposed people of color to levels of nitrogen dioxide — which emanates from cars and industrial sources and can cause respiratory problems — at an average rate 38 percent higher than for white people (Covert, 2016).

The location of Black and brown communities near sources of pollution springs from racist government policy traceable back to the early part of the 20th century. In the 1930s, federal housing agencies redlined black neighborhoods, locking black people into crowded city centers, while helping white people flee to the more pleasant, spacious, and verdant suburbs.

A study conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Center for Environmental Assessment and published in 2018 in the American Journal of Public Health examined facilities emitting air pollution along with the racial and economic profiles of the surrounding communities. The study found that Black Americans are subjected to higher levels of air pollution than white Americans — regardless of their income level. Black Americans are exposed to 1.5 times as much of the sooty pollution that comes from burning fossil fuels as the population at large (Villarosa, 2020). This dirty air is associated with lung disease, including asthma, as well as heart disease, premature death, and now COVID-19.

Fun and Fresh Air

A core belief that both centers and grounds us in this work is that camps owe it to their campers to create a place of belonging for all. That means meeting campers where they are to fulfill the promise we make each summer — which is that camp can be transformational.

What does it look like to create a place of belonging for all campers given their demographics or medical histories? Here are some things you can do to be inclusive of all campers:

- Know your campers. Review health histories with a member of your health center staff to know the campers’ medical needs. Ensure that your acceptance practices are unbiased by conducting these reviews after the campers have been accepted.

- Hire the right folks. When interviewing your nurses, ask if any specialize in asthma or respiratory conditions.

- Prepare your team. If group counselors carry inhalers for campers in a medical bag, do daily sporadic med bag checks to ensure preparedness.

- Share daily air quality index. During your camp’s version of news and announcements, share the air quality index for the day and what that means. Thanks to the weather apps on our phones, this information is readily available and can inform our programming decisions. Maybe we move an activity indoors if the air quality is bad.

- Adjust your notion of what camp is supposed to be. If your idea of camp does not meet the needs of your campers, be flexible. For example, if walking a long distance across campus to get from one activity to another poses a risk, change locations, even if the far pitch is the better one.

Kids always need camp, and they need it now more than ever. More importantly, kids need a camp that meets their needs. So let’s do that.

Kindling Connections

Allison Smith wrote this section of Trail Mixed. Allison brings 20 years of experience working with youth of all ages, primarily in urban areas and communities of color. She has designed and led programs focused on social-emotional learning, health education, leadership skills, and academics, both in schools and outdoor education settings. Allison currently serves as a strategic consultant to nonprofit organizations.

I grew up in a mountainous, subrural community where at certain times of year you were just as likely to run into a black bear as you were your neighbor. The town’s motto boasted being a “Clean, Green Community” nestled along the Appalachian Trail where the woods and lakes turned most of us who grew up there into outdoor enthusiasts. We spent all our out-of-school time wading in streams, digging in the dirt, and exploring trails. When I was young, I assumed that everyone developed this same bond with nature and the environment where they grew up.

I left my hometown at 18 and my career brought me to urban areas serving primarily communities of color. In Jacksonville, Florida, I served as a counselor to adolescent youth, and I would often meet with my students and their families in their homes. I relished afternoon visits with grandparents and the intimacy and connection that came with being invited into someone’s home. But with the privilege of being let in, I also saw the subpar living conditions of public housing communities and crumbling older homes, I saw neighborhoods plagued by waste, and I noticed a complete absence of green spaces contributing to poor air quality and higher temperatures. It also struck me how many of the families I served had a parent or caregiver with a serious, long-term illness. Sometimes it was cancer, sometimes it was lupus, or sometimes it was severe respiratory issues. Without yet knowing the systemic causes or the statistics of health disparities in communities of color, I had a deep sense that the families I served experienced these severe health issues at much higher rates than people in my home community. And then I witnessed the ripple effects these health issues caused — students missing school to help at home, financial strain from medical bills, and deep trauma that comes from watching a loved one suffer or losing them altogether.

I learned more about environmental racism and the ways cities across the United States have subjected communities of color to pollution and toxic waste that would not have been accepted in my “clean, green community.” This understanding proved useful as I moved to Newark, New Jersey, to found Central Avenue Middle School, an Uncommon School, in downtown Newark. During my time as a school leader, I frequently put my first aid training to use deploying a pulse oximeter to check oxygen saturation levels for students on poor air quality days or setting up a nebulizer for a student with asthma who played too hard in gym class. Knowing that environmental conditions also affected allergies, I would arrange special accommodations for students whose teary, puffed-up eyes kept them from performing their best on the annual state test. And as Newark succumbed to a water crisis, and it suddenly deemed my home to have unsafe drinking water, I shared the fear and outrage with my students and their families as we worked to ensure that our school had safe drinking water.

These disparities and their effects were once again highlighted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. As we first isolated ourselves in our homes, schools aimed to provide a sense of structure and normalcy through online learning, but faced with preexisting conditions from environmental racism, students of color and their families endured the trauma of illness and death before many of us could fully wrap our heads around the severity of the virus. Once again, these negative consequences sprawled beyond an individual’s health affecting families and communities.

As we finally had some reprieve from the pandemic, this summer I had the pleasure of serving at Change Summer camps in Bristol, Rhode Island. I was grateful to be among a team that closely mirrored our camper population. They understood the unique hardships the pandemic put on campers of color and what it would take to best support them. Our counselors inherently understood the effects of environmental racism and that “reveling the great outdoors” may require different precautions or accommodations for campers of color suffering from respiratory illness and allergies. This understanding ensured our campers were safe and happy throughout the summer.

As educators in a school, camp, or outdoor setting, it is our duty to understand the systemic and structural forces that shape the experience of participants of color — be it a physical condition or the emotional impact — so that we can provide responsive programming. As outdoor enthusiasts, it is our duty to learn about the history of environmental racism and to hold businesses and our governments accountable for their environmental practices and policies. That way when we advocate to keep our communities clean and green, we are not dumping the problem in someone else’s backyard.

Allison, we thank you.

References

- Brown, P., Mayer, B., Zavestoski, S., Luebke, T., Mandelbaum, J., & McCormick, S. (2004). Clearing the Air and Breathing Freely: The Health Politics of Air Pollution and Asthma. International Journal of Health Services, 34(1), 39–63. jstor.org/stable/45131274

- Bullard, R. D. (1993).The Threat of Environmental Racism. Natural Resources & Environment, 7(3), 23–56. jstor.org/stable/40923229

- Bullard, R. D. (2003). Confronting Environmental Racism in the 21st Century. Race, Poverty & the Environment, 10(1), 49–52. jstor.org/stable/41554377

- Clark, N. M., Brown, R. W., Parker, E., Robins, T. G., Remick, D. G., Philbert, M. A., Keeler, G. J., & Israel, B. A. (1999). Childhood Asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107, 421–429. jstor.org/stable/25071006

- Covert, B. (2016, February 18). Race best predicts whether you live near pollution. The Nation. thenation.com/article/archive/race-best-predicts-whether-you-live-near-pollution/

- Villarosa, L. (2020, July 28). Pollution Is Killing Black Americans. This Community Fought Back. The New York Times Magazine. nytimes.com/2020/07/28/magazine/pollution-philadelphia-black-americans.html

Briana Mitchell is the director of AF Camp and co-founder of S’more Melanin, a platform dedicated to providing resources for BIPOC camp professionals.