Anton, Maya, and James march into camp on opening day with nerves and excitement, just like any other camper or staff. They have brought the items on the camp list, their eyes are wide with uncertainty, and their parents are nervous to leave. Why? Because Anton, Maya, and James are on the autism spectrum, which is a spectrum of abilities that can make trying new things, meeting new people, and fitting into a new environment quite challenging.

With 1 in 54 children in the United States currently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), these children and adults will be applying for camp and camp positions. Understanding ASD and what it means at camp can prepare and introduce camp staff to the unique qualities of these individuals.

The behavioral diagnosis of ASD infers that an individual has limited social communication skills that interfere with their relationships, and that they demonstrate repetitive, stereotypical behaviors. The spectrum is a wide range of varied abilities, from highly verbal to no speech at all; highly sensitive to sensory stimuli to no adversity to varied input; and the tendency to demonstrate repetitive behaviors like hand flapping or repeated scripting to few unusual behaviors.

Do these differences of social communication skills and behavior get in the way of a positive camp experience? Not really, as long as supports are in place, staff are aware, and everyone is open to the “camp magic” looking a bit different.

At our camp we talked about ASD as its own culture, discussing how we could build the bridge between the camp culture and the culture of autism. In general, culture can include language, social interaction, and knowing how to behave in certain situations. More specifically, camp cultures can encompass varying traditions and can include special songs, themes, and routines alongside behavioral expectations. The culture of ASD can include challenges in understanding social rules, accessing language especially in unusual/stressful situations, and behaviors that may be out of the norm.

Mixing and bridging cultures can bring benefit to everyone. We learn:

- To interact in new ways

- To find our voices and use them respectfully

- To not simply tolerate but to truly make space for every person

Things are changing, and it’s time for more inclusivity. It’s time for kids with ASD to go to any camp and for young adults with ASD to work at camps. And high time for camps to make a few tweaks to make it all possible.

Change is not easy, because the human mind prefers certainty and “to do it like we have always done it.” Yet change will benefit everyone. Including everyone in camp will allow more personal growth and more varied communication — and teach tolerance and kindness. Expanding camp communities to include campers and staff with ASD can truly embrace the goal to learn about differences — not to change them, but to appreciate everyone.

Camps can take four beginning steps to intentionally support all campers and staff and instill a sense of belonging in the camp community. These initial steps call us to:

- Understand the gifts and the challenges of having autism spectrum disorder.

- Be aware of what social engagement truly is and looks like.

- Teach everyone skills for social inclusion.

- Provide visual supports for everyone.

Understand ASD

Generally, the gifts of individuals with ASD are as diverse as the gifts of others. However, many people with ASD:

- Have unique areas of interest

- Tell you what they think (quite literally)

- Move at their own pace

- Are visual learners

- Have the gift of paying attention to details

Often people on the spectrum have challenges with:

- Anxiety

- Sensory overload

- Understanding social rules

- Changing routines

- Understanding others’ perspectives

Individuals with ASD have the drive for membership and belonging that all people have, though they sometimes have challenges with the skills to make this happen. Remembering that every individual on the spectrum is unique and that ASD is just a small piece of who they are as a person will help to build relationships.

| As a 16-year-old with ASD and anxiety that appears to mainly impact his ability to understand hidden social rules, Anton wants to be included in the camp teen dance. But the music is blaring too loud for him, and he doesn’t seem to understand when his song choice will be played. His reaction to these concerns could make the teen dance a bust. Thankfully, Anton’s camp team has his back. They understand his autism and have noise-canceling headphones at the entrance, as well as a written, sequenced playlist so he can see when his songs will be played. These small modifications make the dance a success for Anton and his team. |

What Is Social Engagement?

Social skills are the context for all learning. Positive social skills are a predictor of the choices we will have as we move into adulthood and, most of all, the connection to our hearts. Because we all long to belong.

We begin with social engagement, a term that has been used more often since the pandemic started. Social engagement is the foundation for all social skills, and camp has a history of supporting and encouraging such engagement. It is intuitive for many individuals, but it may not “just happen” for those with ASD. Knowing what engagement looks like can help us identify it and set up the conditions for it to happen when it’s not occurring naturally.

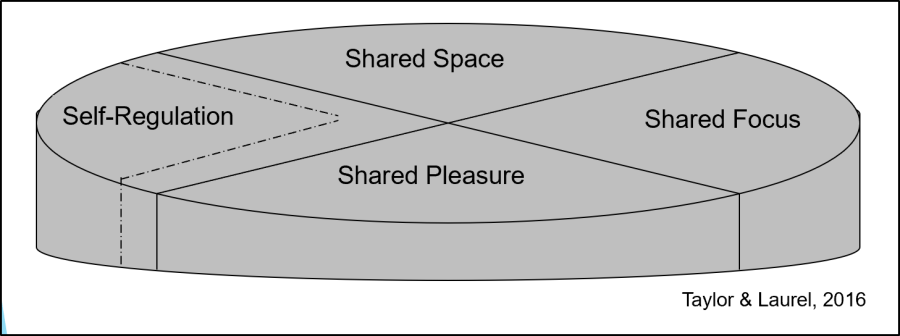

Taylor and Laurel (2016) describe social engagement with the following four components (see Figure 1):

- Self-regulation

- Shared space

- Shared focus

- Shared pleasure

Figure 1: The Social Engagement Components Pie Chart

Self-regulation is the piece on the left that is surrounded by dashes to make it “pop,” because it’s essential. It’s the piece we address first and the one we go back to time and again as we pursue social interactions. Self-regulation is being in an emotional and physical state to learn and respond positively within an interaction. We all learn to self-regulate — to use sensory input to help our bodies become calm and awake enough to be ready to learn. (Taylor and Laurel call this Calm + Alert = READY.) Some of us, however, are better at this skill than others. We might pace, fiddle with a pencil, listen to music, tap our foot, exercise, get out in nature, sip a drink, or bite our nails. All these sensory strategies help our nervous systems get ready to learn — at school, at home, and at camp.

Common ideas to support self-regulation include:

- Put something in your mouth — gum, hard candy, something to chew (our mouths help us to self-soothe)

- Practice rhythmic movement like swinging, bouncing, or rocking

- Listen to music with a beat

- Be in natural lighting

- Exercise or engage in activities that use our large muscle groups

- Get outside

- Do repetitive activities

- Find a quiet space to get away from the noise

Once we are ready, we move to the next piece of the pie. Shared space is being in proximity with another person. Sometimes we need to get close enough so that others know we are ready to socially engage. We must intentionally take note of what space works for what person, and we need to do this in “real time” during camp.

Moving around the pie, shared focus (both people paying attention to or being interested in the same thing), is where camp staff may need to “stretch.” We all have certain things we like to talk about, but sometimes individuals with ASD have even more unique topics and they like to tell you all about them. Camp staff could get tired of hearing all about the car dealerships in Santa Fe, water heaters, pipe cleaners, Minecraft, terminal diseases, or anime. While these unique topics might not bring as much joy to all staff and fellow campers as they do to campers and staff with ASD, accommodating one’s interest is the place to start.

The final component of the pie is shared pleasure — or enjoying the same moment together. These moments look different for everyone. Perhaps a belly laugh, a smile with one’s eyes, or even a glance. With a person with ASD, it might be a bit more subtle; it may take you a moment to search for it — but by no means is it any less important or gratifying.

It is the synergy of shared space, shared focus, and shared pleasure in the context of a calm and alert state that defines the very special moments of social engagement (Taylor & Laurel, 2016). When we know how to recognize engagement, we can see it. When we see it, we can make it happen more often and with more people. When engagement takes place, we find the magic of connection, and meaningful relationships are formed.

Teach Social Inclusion

What tools can help us teach others to engage? First, we need to set up the conditions to help make social engagement happen. This can feel odd, because for many of us this occurs so intuitively.

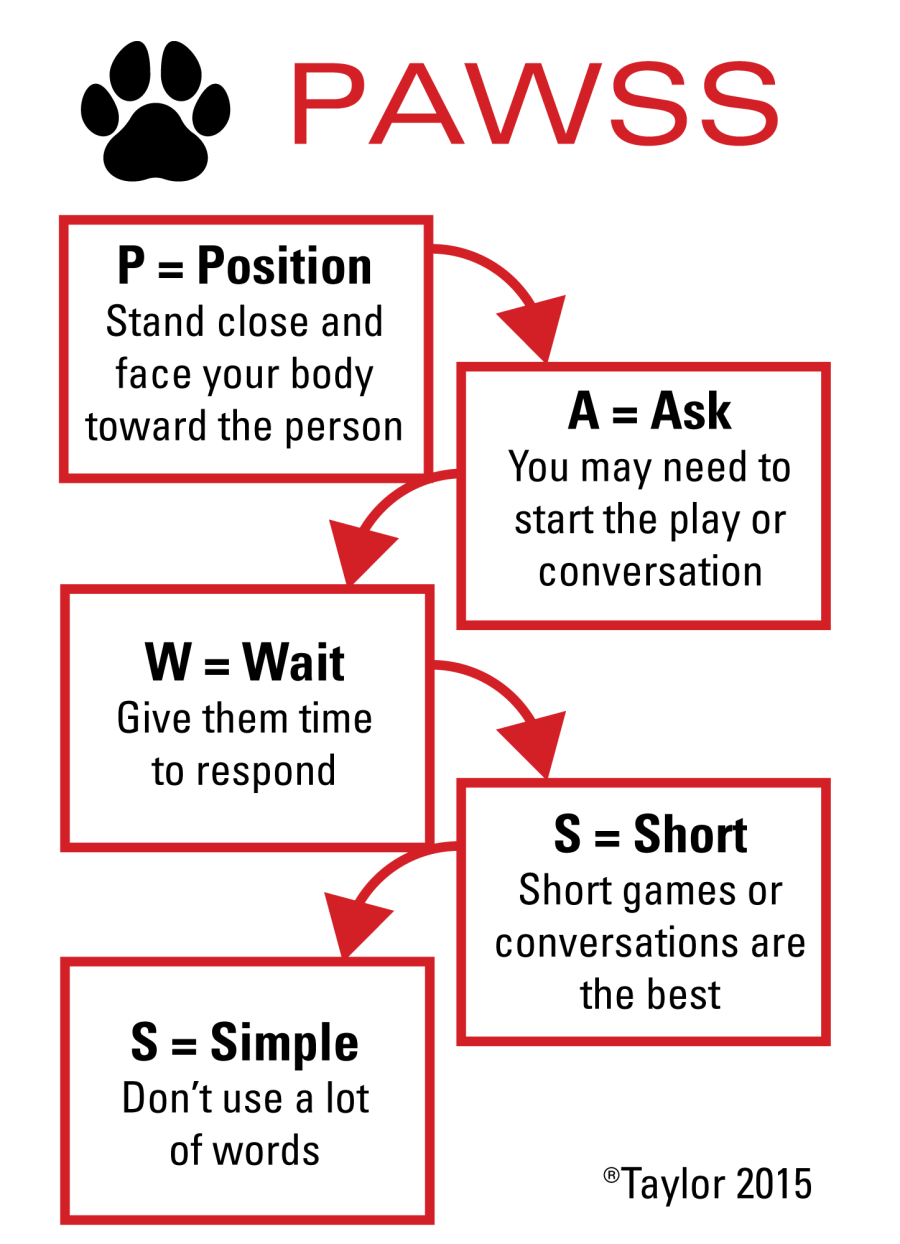

In 2007, the University of New Mexico, Camp Rising Sun developed a peer-mediated program called “PAWSS.” This program was developed, implemented, and refined from 2010 to 2018 to support social inclusion and increase the richness of the camp experience for everyone. The program was assessed each year through a pretest/posttest, and data showed its effectiveness, indicating that the program was beneficial in a variety of settings.

The PAWSS program offers a systematic, structured way to teach staff and campers to support individuals who have challenges with social engagement. It is an easy, effective peer educational program that shows people how to interact with individuals with limited social skills. Each letter in PAWSS signifies an action that can be taught, practiced, and reinforced with campers and staff alike.

Position: Stand at arm’s length away and turn your shoulders toward your communication partner.

Ask: Initiate the question to start the play or conversation.

Wait: Wait for the count of five, and then ask again to give time to process.

Short: Sometimes short games, activities, and conversations are the best.

Simple: Leave out the little words or jargon and use meaningful age-appropriate language.

PAWSS won’t just help campers on the spectrum; it will enable everyone to slow down their social interactions, be more intentional and kinder, and to really take notice of moments of connection.

Figure 2: PAWSS

| Maya appears shy to most and very reluctant to try new activities, yet her camp staff continue to give her choices and allow her time to process the verbal information instead of repeating the question over and over. They count to five before they interrupt her thinking. This extra time enables Maya to find her words and participate in the conversation and choice making. |

Visual Supports

In the past two years we have all learned that visual supports can help us understand unwritten rules. We have stood on “dots” to social distance and followed signs and arrows to create new routines and understand new rules. Likewise, visual schedules and directions at camp can be a respectful way to communicate with individuals who happen to use their eyes more effectively than their ears.

Visual schedules written in a language that makes sense to the camper or staff (words, phrases, pictures) can help an individual know where to go and in what order events are taking place. It helps them to understand what is coming next and what they can look forward to. We often have a big schedule somewhere at camp, but what about a little one that campers or staff can carry so they don’t have to hold the sequence of events in their heads? This simple idea can alleviate a lot of anxiety and help an individual on the spectrum become more independent and at ease.

Directions, song lyrics, or art projects provided as visual demonstrations, pictures, or written words can also give campers and staff time to process the information and understand the sequence.

| James is 19 and working at his first job at camp. One of James’s camp assistant responsibilities is to hand out snacks at campfire. But James gets confused with time and when to start getting the snacks ready. His campfire team understands that a whiteboard visual schedule could help everyone know what is happening at campfire and the sequence of the events. The written word, phrase, or picture can also help us remember. |

When camps intentionally put these four steps into play — understanding ASD, recognizing social engagement, implementing PAWSS, and using visual supports — they begin to make more space for all. The most important goal at camp is to get staff and campers engaged — with each other, with the learning, and with the outdoors.

We, the camp community, have the power to make change happen. We know camp can be a place to let people be who they are, and a place that provides supports so that everyone can participate. Camp can be the place where we truly make space for every person and where everyone is welcome.

Photos on pages 44–48 courtesy of Camp Spearhead, Marietta, SC; Camp Howe, Goshen, MA; The Gow School Summer Program, South Wales, NY.

References

Taylor, K. & Laurel, M. (2016). Social engagement and the steps to being social. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons, Inc.

University of New Mexico, CDD, Autism Program. (2015). PAWSS — A peer training program to support the social engagement of people with autism spectrum disorder. https://unmhealth.org/services/development-disabilities/programs/autism…

Kathleen “Mo” Taylor is an occupational therapist in New Mexico with a 35-year history of working with individuals with autism spectrum disorder. She is a part-time faculty member at the University of New Mexico and runs Theraplay LLC (private therapy business). During Mo’s 30 years of directing and supporting camps for people with disabilities she was the practicum director at Camp Rising Sun. She shares her experience of ASD and camping through trainings around the USA and internationally. Her career is devoted to meaningful “real-life” experiences for all.