Another camp season is complete. After working overtime to ensure that every session was special, enriching, and fun-filled, we camp professionals are finally able to exhale. We did it! The energy, dedication, and tenacity that it takes to run a summer camp is nothing short of heroic, which is why it is typical for camp professionals to use the weeks following the end of camp to squeeze in some well-earned rest and rejuvenation before diving back into planning for the next camp season. However, a third R-word is just as important for camp professionals to tap into at the end of summer — reflection.

According to David Kolb, an American educational theorist, reflection is a key component to the experiential learning cycle for adults in addition to the three stages of acquisition, specialization, and integration (Kolb, 2014). Through reflection, one can begin to assess the effectiveness of the knowledge, skill, and attitude implemented during an experience. This process can help individuals discover the internal assets they possess and make informed decisions about how to navigate future situations. But reflecting as a collective through an intentional debrief can help entire camps refine policies, strengthen employee relations, and define organizational success.

A Lesson in Reflection and Sankofa

Across industries, team debriefs are a tool used by highly successful organizations. As the term debrief suggests, this working meeting is a tactful step to ensure future success by investigating past experiences and their outcomes while they are still current. Although effectiveness and organizational success is the main reason most camps have end-of-season debriefs, these meetings can also be a catalyst for boosting morale, team building, and fostering leadership among camp staff. The idea to use team debriefs as a means of strengthening employee relations draws from both the modern reflective practice and the Sankofa practice of the Pan-African movement.

The modern reflective practice is “a method of assessing our own thoughts and actions, for the purpose of personal learning and development” (Lawrence-Wilkes/Chapman, 2015).The theory behind reflective practice is heavily influenced by the ancient Greek philosophy of critical thinking that was refined by Socrates, paired with the reflective nature of learning rooted in the ancient Chinese philosophy taught by Confucius. Reflective practice is truly meant to help individuals engage in the learning cycle in a way that will prevent the same outcome, incident, or experience from happening twice. Although this method is typically used by individuals, it can be useful in a team setting. Expert Linda Lawrence-Wilkes asserts that “if reflective thinking is to be useful for our learning and development, and for improving our actions and decisions in an environment, then this reflective thinking must include some objectivity. If decisions are based on wrong data, then outcomes tend to be unhelpful, or worse”(Lawrence-Wilkes/Chapman, 2015). To maintain objectivity during reflection, Lawrence-Wilkes recommends using set templates or debrief questions “alongside many other concepts for training, learning, personal development, and self-improvement.”

The practice of Sankofa in the United States draws from a part of the philosophical tradition of the Akan people of Ghana. When it is conventionally translated, the adinkra symbol Sankofa means “go back and get it” (Temple, 2010). Sankofa practice emerged as a way for Black people in the US “to complement intuitive African behaviors and cultural affinities with a more intellectually aggressive study and consumption of the history, philosophy, and values of cultural retention and rediscoveries” (Temple, 2010). For many directly impacted by the African diaspora and whose ancestors were enslaved, Sankofa symbolizes reflection, history, and the importance of letting the past guide present and future action. Like reflective practice, Sankofa practice values both self-reflection and experiential learning; however, Sankofa practice requires practitioners to do research as a follow-up to self-reflection to help individuals process their lived experience. At the heart of it, Sankofa practice is about understanding culture and seeking knowledge to validate or improve the quality of one’s experience.

By incorporating aspects of both Sankofa and reflective practices into the end-of-season debrief, camps can include insight from both seasonal and year-round staff throughout the strategic planning process and intentionally seek industry best practices for handling incidents rather than addressing them as they come. This demonstrates to staff, regardless of title, that their thoughts and experiences are important to the camp and directly influence its culture. Additionally, these methods of collective debriefing help staff process their summer experiences as a team and encourage them to research new information and share these resources among the team.

The Strategic Team Debrief

The Harvard Business Review defined debriefing as, “a structured learning process designed to continuously evolve plans while they’re being executed” — and identifies debriefing as being critical to “accelerating projects, innovating novel approaches, and hitting difficult objectives” (Sundheim, 2015). In his article, “Debriefing: A Simple Tool to Help Your Team Tackle Tough Problems,” Sundheim says that the key components to creating a successful culture of debriefing are: 1) building a routine debrief schedule, 2) developing meeting norms, 3) developing set guiding questions, and 4) coding lessons learned (2015).

Components 1 through 3 enable an organization to set expectations around the debrief that communicate to staff the intentionality behind the exercise and reassure them that it is meant to aid the organization in practicing a growth mindset. A camp can also use this structure as a resource in addressing critical incidents as they arise.

Then coding helps to organize and preserve the points that emerge from debriefing sessions. Sundheim writes, “Make sure you capture lessons learned in a usable format for later reference/use. At a minimum this is taking notes and distributing them to the members present. Other methods can make the information more readily available to a broader audience” (2015). Overall, the purpose of capturing debriefing outcomes is to ensure that the information remains useful and is able to be clearly communicated to future staff and other stakeholders.

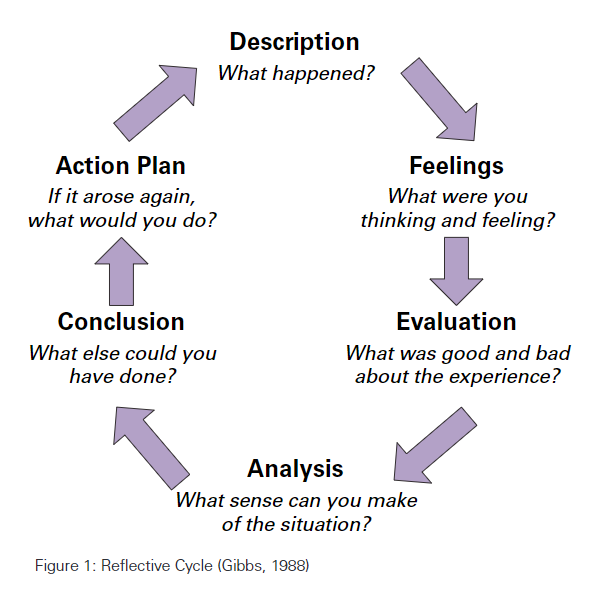

Developing a camp culture that utilizes debriefing is beneficial for all of the aforementioned reasons, but particularly useful at the end of camp. The end-of-season debrief helps leadership gain an understanding of what worked, what didn’t work, and what changes camp should make to ensure that next summer is more successful than the last. Graham Gibbs, Reflective Cycle, shown in Figure 1, demonstrates a framework that marries the two ideas of reflection and action. It provides structure to examining experiences to learn from them. Given its cyclical nature, this framework lends itself particularly well to repeated events — like camp — enabling camp leaders and staff to learn and plan from both triumphs and missteps (The University of Edinburgh, 1970).

Kindling Connections

This section of Trail Mixed was written by Mary Oluokun.

Oluokun is the director of summer residency programs at The AnBryce Foundation and brings over nine years of experience working with youth of all ages, primarily from under-resourced communities, using outdoor education as a tool to teach and foster social-emotional skills that participants can use to navigate their worlds. She writes:

“The Art of Debrief” is a title a past supervisor of mine would use to name his staff training session on debriefing, and it still resonates with me today. As a young child growing up, everything, every experience, always had a lesson to gift us — and without knowing exactly what I was doing, I would “debrief” an experience, either with friends, family, or alone.

Some years later, I was going through adventure course and backpacking training, and there was one particular facilitator I would shadow who I will never forget. He seemed to move like magic as he ran activities with participants and asked debrief questions without making it seem like debriefing. He took them through a journey that was never rushed and at the end resulted in the gift of an “aha” moment for every member of the group, me included. It was then that I understood that running fun activities is great, but being able to guide a group through shared thoughts and experiences using questions, being attuned to the group and letting them lead their own journey as they process the experience and apply it to their personal lives is crucial.

Fast-forward another couple years, and I was now leading my groups through wilderness running activities. I can remember writing down my debrief questions for the activities that I would run. However, what happened when I began asking my questions is that the group would sometimes change the direction I was hoping to take the conversation in — and I loved it! I loved it because it felt authentic, and the conversations lasted beyond that activity and sometimes for several days after!

One specific debrief that still makes me smile today was with a group of mostly soon-to-be first-year college students during a backpacking trip. My partner and I ran an activity called B.E.A.R. (be educated about respect), and the conversation carried throughout the five days on the hike and even back on campus. It led from one topic to another. Thoughts and ideas were challenged, and I learned so much from each participant about what respect meant to them. It made me appreciate even more that there are many different ways to understand one idea, but there must be safe and brave spaces available to be able to welcome all thoughts and ideas.

We thank you, Mary.

For More Information:

Here are some additional resources when planning for your end-of-season debrief:

- Mike Cardus’s article "Team Learning from Reviewing What Works and How to Improve," and video Working Well and Team Improvement Process.

- Colin Beard and John Wilson’s Experiential Learning: A Handbook for Education, Training and Coaching

- Listen to the Debrief2Learn Podcast

Makela Elvy, M Ed, is an environmental educator and camp enthusiast. Along with Briana, she is also the cofounder of Smore Melanin — a platform dedicated to providing resources for BIPOC camp professionals. Over the course of her career, Makela has held camp positions ranging from head counselor to summer program director. Her experience includes nature interpretation, curriculum development, and the creation of a 10-week venture program rooted in experiential learning.

Briana Mitchell has been a camp attendee since the age of six and a previous camp counselor and Teach for America Corps member. She is the director of AF Camp, a Change Summer camp, where she works to create high-quality summer opportunities for students that will increase their overall confidence, responsibility, curiosity, and independence. She is also the cofounder of Smore Melanin — a platform dedicated to providing resources for BIPOC camp professionals.

Photo courtesy of Camp Spearhead, Marietta, SC.

References

- Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

- Kolb, D. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Second). Pearson FT Press.

- Lawrence-Wilkes/Chapman, L. (2015). Reflective practice. Businessballs.com. Retrieved from Businessballs.com/reflective-practice.htm

- Sundheim, D. (2015) Debriefing: A simple tool to help your team tackletough problems. Harvard Business Review. Retrieve June 11, 2021, from hbr.org/2015/07/debriefing-a-simple-tool-to-help-your-team-tackle-tough-problems

- Temple, C. (2010). The emergence of Sankofa practice in the United States: A Modern History. Journal of Black Studies, 41(1), 127-150.

- The University of Edinburgh. (1970, November 11). Gibbs' Reflective Cycle. ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle