This summer, as you enjoy your time on staff, your days will no doubt be filled with plenty of fun and memory-making. And just like in any job, there are bound to be some tougher times when your patience and ability to remain calm and kind will be tested.

When that happens, keep two things in mind: (1) this is a normal part of working in a busy, exciting, fast-paced job with kids, and (2) what you say and do in these moments can have a direct impact on how the situation turns out. When things get intense, remember these tips and strategies for what to say (and maybe more importantly, what to avoid saying) in those high-emotion moments.

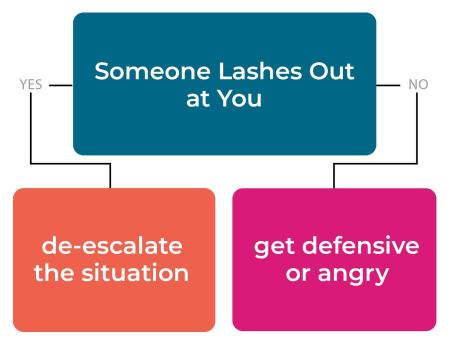

Someone Lashes Out at You, and It's Loud and Scary

When people put a load of emotion out there, it can get intense quickly. Depending on your individual experience with this kind of thing, your gut reaction is often either to run and hide or to dig in and fight back. That's the "fight or flight" reaction, and whether you choose to engage or to run, your brain sends your body a burst of adrenaline to help it respond. That chemical reaction flooding through your system can make staying calm and thinking things through difficult. The best thing to say in that moment — instead of pretty much anything in a defensive or angry tone — is, "I want to help, and I can only do that when you're speaking to me calmly."

Why does this help? Our two-fold goal whenever someone is being loud and scary in that way is to de-escalate the situation and make sure everyone stays safe (both physically and emotionally). When we respond in a way that matches the hostility and stress coming at us, we further escalate the situation.

If you don't remember what to say, or if you think what you will say is going to make things worse, you're better off saying nothing at all (using silence) or using attentive listening noises ("mhmmm") and letting someone rant rather than trying to be heard over the noise.

If they can hear you, however, the "I want to help" recommendation is a great go-to. You can also try "I hear that you're frustrated. It would be easier for me to listen to what you're saying if I am not being yelled at."

The goal is to validate their feelings (you may not like how they're being shared, but that doesn't make them any less valid), and then to let them know you're there to help. You want the person to receive several messages in this situation, including, "You have a right to feel that way," "I'm not the enemy here," "It's not OK to yell at me," and "I am also a human being with feelings."

Whenever you validate feelings and ask a person to do something (in this case, take it down a few levels), you want to use "and" instead of "but" language. Consider the difference between these two statements: "I want to help, and I . . . " vs. "I want to help, but I . . . ." The former keeps the brain listening for what comes next. The latter signals the brain to get its defenses ready, because it won't like what it hears next. (If you're not sure why this works, practice a marriage proposal in your mirror at home. Start with "I want to marry you, but . . . " and you'll see why replacing it with "and" will go much better.)

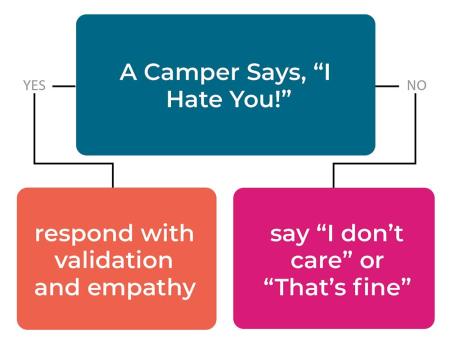

A Camper Says, "I Hate You!"

You're going to spend the summer doing everything possible to make sure kids have an amazing time at camp. You'll work hard every day for their benefit. So, it can be hurtful and surprising when a camper says something mean to you. Don't they realize how much you're doing for them? Yes, they do. Just not in that moment.

When someone you care about says, "I hate you," it's hard not to take it personally. I mean, they literally just said they hate you. That's pretty personal, right? Actually, it's only personal if you assume that the message means what it sounds like. Good news: it doesn't. "Hate" is one of the strongest feeling words kids know, and they associate it with anger, hurt, and disappointment. They might use "hate" when they feel stuck or out of choices. "I hate flag football!" might actually just mean "I'm worried that I'm not good at this and others will notice," or "I wanted to be in another activity." Most of the time, "I hate that" means "I'm sad/disappointed/angry" or "I don't like what you said/did."

While it might be tempting, you don't want to respond directly to "I hate you." Saying "I don't care" or "That's fine," or even "Yeah, right back at you!" might feel good in the moment, but it's your job to be the bigger person in that scenario. Trust me when I say this: it won't feel good after the fact to realize that you sank to the level of a very grumpy seven-year-old.

Later, when feelings aren't so big, you might decide to discuss with the camper how they could choose different words next time to avoid hurting people's feelings unnecessarily. While you should take advantage of any chance you have to help campers work on their social-emotional skills, that learning really does come second in importance to cooling down the situation.

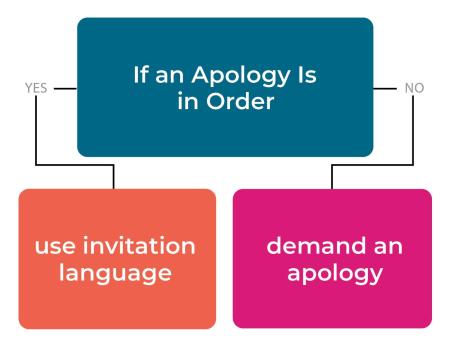

If an Apology Is in Order

There will come a time this summer when you will need to help two campers mend hurt feelings or address harm that has happened. Conflict (also known as "storming") is a normal stage of group building and an expected part of friendship building, both types of building that occur every day at camp. And when the time comes that a camper lets you know someone has hurt their feelings, resist the urge to make that camper apologize.

What? Yes, resist the urge. Apologies have their place in repairing hurts and harms, and depending on how you encourage their use, you can actually create further harm rather than patch things up.

With apologies, it's all about inviting rather than demanding. If you say to a camper, "Hey, that's not acceptable behavior. You owe Sam an apology right now!" you're setting up an unnecessary power struggle. You impose your will on the situation and take away the camper's ability to make their own choice. Demand language like "you need to" or "you have to" rarely works with kids. In fact, it's almost guaranteed to further escalate the situation the same way that "but" instead of "and" does. It almost begs the camper to respond with "Yeah? Make me." That path leads nowhere good.

Demanding an apology "right now" can create an additional stumbling block. During the heat of frustration is the worst time to demand anything. It's in everyone's best interest to take a couple minutes (or, really, as long as it takes) to cool down and understand what happened before attempting to simply patch things up. If you skip the steps of decoding (figuring out what caused the hurt) and de-escalating, and just ask two kids to shake hands and mutter "I'm sorry," chances are you'll be handling the same situation again in just a few hours.

The best way to ensure that an apology is helpful is to give everyone involved time and space to be ready to give and receive that apology. Instead of demanding it, use invitation language to let the camper know what you expect. "Alex, you may sit on the bench while you think things through. When you're ready, Quinn has said that they would appreciate an apology." This makes clear to the camper who has created the harm that they need to take a break from activities with the group until they are willing and able to make things right, while also giving them control over their own choice of when and how to do that. This way, they're less likely to refuse or further escalate the problem.

Apologies also aren't magic potions; they don't automatically make the hurt go away — and you can help campers understand that. I encourage you to look at these situations with a restorative lens, and ask each camper what they need to do or say (or what they need the other person to do or say) to feel that the situation is resolved. It may be an apology, or it may be a different and better solution.

A Camper Tells You, "It's Not Fair!"

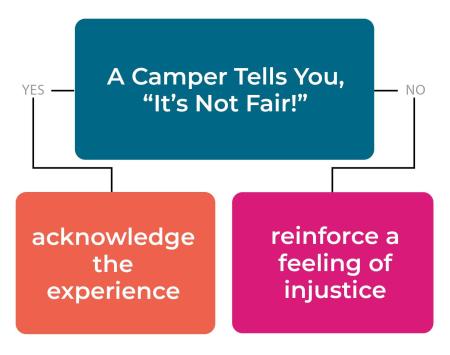

As with "I hate you," "It's not fair" is another example of words that do not reflect a camper's true meaning. It's rarely actually a matter of "fairness" that campers are upset about. Instead, they may be having trouble seeing the big picture because they're missing information or simply haven't yet developed their perspective-taking skill. For younger kids, "fair" usually equates to "what I want," while "unfair" is their version of "not what I want."

You may also come across campers who are dealing with something in their lives outside of camp that truly is unfair, and for whom the situation at camp is triggering a bigger underlying issue. Still another possibility is that they may have a distorted perception that others are more fortunate than themselves ("Cam always gets . . . "). What you don't want to do in this situation is to reinforce a feeling of injustice, which can lead to lasting feelings of hopelessness or helplessness.

So, for example, after a team win where a camper thinks it's unfair that they weren't acknowledged as MVP even though they made three goals, avoid saying something like, "I know, someone else always get the credit!" Instead, acknowledge the experience the camper is having ("You played great. I know it's hard for you to see others get recognition right now"), and then use the opportunity to teach empathy and sportsmanship. "Devin worked really hard for that last goal. Let's congratulate them together," or "It's OK for Devin to be excited for this win. You've had lots of great things happening for you on the field this summer." This can help campers see that sharing the credit doesn't diminish their own achievement.

Sometimes the situation isn't as obvious as less-than-great sportsmanship disguised as "unfairness." If you're not sure why a camper feels something is unfair, fall back on your number-one, go-to strategy: validate and decode! After acknowledging that they have a right to their feelings, ask them about the perceived unfairness. "I'm curious. What makes you say it's unfair? Can you explain what you mean?"

As campers get older and their understanding of the world around them increases, you might also take the opportunity to explain the difference between fairness and equity. "Fairness doesn't always look the same. In our group, I make sure everyone gets what they need, which might not be the same for each of you." Helping campers understand that fair is not equal — and equal is not necessarily equitable — is a lesson that will impact their lives far beyond summer camp.

Along those lines, here's a final word of advice on fairness. If a camper has the perception that something is unfair, and in fact it is not unfair, the strategies already described will work. Sometimes, however, things may truly be unfair. It's your job as a trusted adult to carefully examine the situation and make sure that there is truly not an injustice taking place, and if there is, to disrupt it.

Final Thoughts

Even the best wordsmiths and fancy talkers get tongue-tied when emotion is running high (or when faced with an overtired, overheated, overwrought camper). It's OK not to always know the right thing to say in the moment, and it's OK to say nothing. If someone asks why you aren't responding, you can politely say, "I was just listening" or "I didn't want to interrupt you." You'll have a chance to get your say — but shouting it over someone else or demanding that kids do what you want them to when they're upset is never the way to go. So this summer, during those few stressful situations that interrupt your awesome experience as camp staff, be the voice of calm and reason, and you'll help get your campers back on track so everyone has an amazing time.

Discussion Questions

- We each have personal triggers that make us likely to respond more intensely in certain situations. What kind of things at camp are likely to "push your buttons" and might cause you to respond in a way you don't mean? What can you think of to say or do instead in those moments?

- Should a child be required to apologize if they've hurt someone's feelings? What purpose does an apology serve? Are there other "fixes" that could be used instead?

- What kind of body language does someone show when they are getting escalated vs. when they are calm? What are some ways to help an upset camper "cool down" before you attempt to help them discuss their feelings?

Emily Golinsky, MS, provides training, consulting, and advocacy for camps, schools, and youth development organizations through her company Bright Moose LLC.