While we relish the opportunity to write each edition of the column, this issue is particularly exciting as it is composed with the hope that it is useful for those who will be interfacing directly with campers this summer. Each camp that runs a program this summer will brave the complexities of delivering on the promise of camp magic within a 2021 context. The enormity of this undertaking is not lost on anyone. This summer’s pre-camp orientation will likely be akin to drinking from a fire hydrant. Given the constraints of this camp season in the face of the pandemic, you will likely receive double the amount of information in the same amount of time as in summers past.

Two of the values that serve as our North Star are community and knowledge. These principles guide our work, and when tasked with a challenge, we are called back to them. We want to provide you with valuable, meaningful information that is at the same time feasible and digestible. It is that framework that leads us to the topic of the power of language.

Language — it isn’t an add-on strategy or back pocket game, but something the majority of us already possess. So, let’s keep it simple and use language as a key lever to support all of the work being done to make this summer the successful one that we all need.

Author Rita Mae Brown says “Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.” This summer, we are going to camp. Our aspiration is that the direction camps are going in is one of intentionality and inclusivity — so language at camp should reflect that.

Language as a Means of Social Identity

The desire to fit in is natural for all children as they form their social identities. Despite the advice to be unique and to love one’s authentic self, grade-schoolers often seek the approval of their friends, role models, and even in some cases their bullies. In your role as a summer camp professional, you assume the duty to uphold camp’s number one priority — safety. In addition to being responsible for the campers’ physical safety, you are also tasked with creating an environment in which campers feel a strong sense of emotional and psychological safety too. One way to create safe space at camp is through language, both through the mindful use of inclusive words and phrases, and by allowing children from diverse cultural backgrounds to communicate and express themselves openly without correcting their linguistic variation.

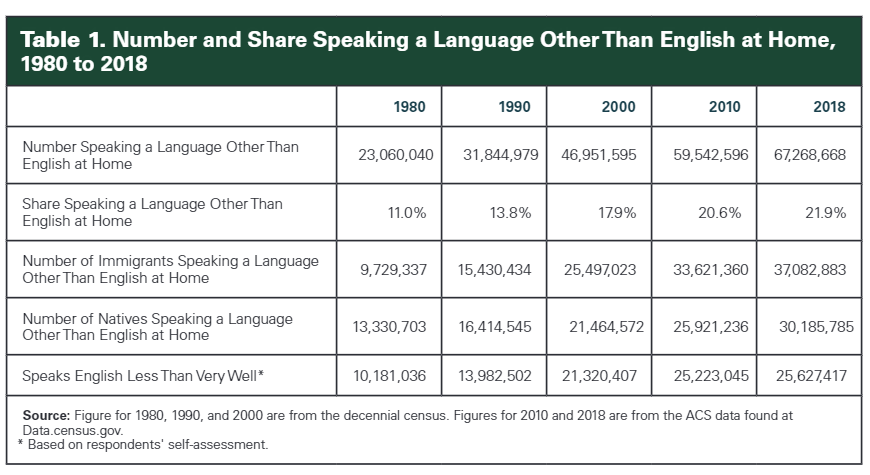

Linguistic variation refers to the different accents, dialects, word choices, and grammar associated with language. Sometimes these variations manifest regionally (like the iconic southern drawl), historically, or as a result of immigrating and learning a new language. In 2019, The Center for Immigrant Studies published a report about the increase of foreign language speakers in the United States. As shown in Table 1, the percentage of people speaking a language other than English at home has nearly doubled since the 1980s.

Table 1. Number and Share Speaking a Language Other Than English at Home Statistics Graphic (Zeigler & Camarota, 2019)

This statistic indicates that with the increase in racial and ethnic diversity in the US comes an increase in populations that are speaking with language variations such as accents and dialects, or even multilingual. Another statistic revealed by this report was that in 2018 more than 25,000,000 people indicated via self-assessment that they spoke English “less than very well.” Although it is unclear what factors influenced these responses, whether it be a history of social interaction or not yet mastering a standard English curriculum, this particular statistic illuminates the way those “other than English speakers” feel about themselves, their self-esteem, and their ability to communicate with others in the US.

Code-Switching as a Means for Survival

To combat some of the psychological effects that surface as a result of linguistic discrimination, many speakers tend to code-switch. By definition, code-switching is the switching between languages or dialects during a single conversation. But code-switching doesn’t always happen seamlessly, especially not for those with distinct accents. In “Accent, intelligibility, mental health, and trauma,” Tej Bhatia explains that accents have a biological component that make it very difficult to turn off after adolescence, thus it is challenging for immigrants and people with pronounced foreign accents to blend in or speak another language flawlessly. Throughout his research Bhatia continues to emphasize the power structure associated with language and how it is upheld by those in power, the “prestigious,” via education, media, and laws (2018) that reinforce a social standard. One example of this would be the association of SAT words with intelligence and higher social status versus the association of American Black English or Ebonics with less intelligence and lower socioeconomic status, as depicted in literature, slogans, and film. Conversely, Bhatia asserts that “the characterization of the language used by those with less social power as ‘improper’ language, often becomes an object of ridicule or stigmatization” (2018).

Stereotypes are one of the most common negative byproducts of linguistic bias (Beukeboom & Burgers, 2017) that render those bullied or taunted because of them vulnerable to significant psychological effects, including lifelong trauma and even suicidal ideation (Bhatia, 2018).

Similarly, code-switching is also a term heavily tied to the Black American experience as a means of self-preservation. In this context, code-switching refers to one’s ability to suppress aspects of their cultural identity and self-expression to blend into the dominant white culture and avoid feelings of isolation and otherness. In her TEDx Talk, Chandra Arthur recalls that she learned to code-switch around the age of nine, and it began with someone policing her use of the word “ya’ll” as opposed to “you all” (Arthur, n.d.). Continuing to reflect on her personal experience, she asserts, “When we look more closely at code-switching and who is expected to make the switch, we discover a hidden reality, and that reality is that the expectation of code-switching threatens true diversity.” Her statement further reveals that power dynamics are evident in language. It also reveals that this same power dynamic aligns with a white-dominant social structure. If campers are fearful of fully expressing all aspects of their identities at camp, are we truly creating a safe space that allows camp magic to manifest?

Linguistic and accent discrimination, the unfair treatment of an individual based solely upon the characteristics of their speech, are considered “the most powerful and overlooked feature responsible for social discrimination” according to Bhatia (2018). Despite the proposed English Language Unity Act of 2017, the US remains a country with no official language, and census data reports that approximately 350 different languages are spoken in the US. So it begs the question — is correcting linguistic variation in campers’ speech really essential, or preferential?

Here are some things you can stop or start doing this summer to make camp feel a little bit safer:

- Don’t imitate any accents. This has the potential to be offensive and is usually often based on a more popularized version of language, but neither people, nor ethnic groups are monolithic.

- Avoid correcting pronunciation. Contextually, language is often preferential. It is critical that we do not make our manner of speech the default. Allow campers to express themselves in a way that feels natural to them.

- Find alternative ways to express “no.” Everyone has been through a lot this past year, some more than others. Hearing the word “no” could be received as being shut down, which can be difficult to digest at any point, and can be especially triggering in light of all that children have endured.

Kindling Connections

This section of Trail Mixed was written by Tabassam Alam.

Alam is a youth development specialist originally from Queens, New York. She had the opportunity to mentor young people through Teens for Racial and Ethnic Awakening (TREA), a youth leadership program that encourages open and honest conversations among youth. In 2019, Alam achieved a bachelor’s degree in History, with honors, from Lafayette College and is currently employed as a senior experiential education facilitator, allowing her to continue to impact the lives of dozens of youth. She writes:

Growing up in a traditional Bengali-Muslim household, I never went camping, unless sitting on my couch watching The Parent Trap or Camp Rock counts. For me, camp seemed like this magical place where special people were granted access to do all kinds of fun and exciting things, but I never felt it to be a place for people who looked like me or who grew up in a non-Western culture. After graduating college in 2019, I decided to join the camp world out of pure curiosity. It was during this time I noticed the lack of representation of minority groups in the field, and although this was not a surprise to me, I did feel a level of discomfort thinking about what this lack of representation would mean for the kids we serve.

Identity is a tricky and confusing thing to talk about, especially when you’re a brown Muslim woman working in a predominately white and male field. Because of this, conversations surrounding identity and representation don’t always feel welcome, which is an even greater challenge, as it doesn’t make room for breaking down stereotypes and authentic storytelling. I can recall several instances at camp when I experienced the impact of racial and cultural stereotypes firsthand. One moment that comes to mind was during my first week at camp. I remember the yellow bus pulling into the driveway and, one by one, all the kids getting off the bus. Now, it’s important to note that compared to my colleagues, I have more melanin in me, and when I speak people can often guess I’m from somewhere in New York. As I made conversation with the kids, a man came up to me. He introduced himself as the chaperone for my group, and I introduced myself as the facilitator. He then asked me where I am from. I said, “New York,” but I could tell there was going to be more to the conversation.

He let out a laugh and said, “No, I mean where are you from from?”

Because this wasn’t the first time I’d gotten this question, I figured he wanted to know my ethnicity, since I was the only nonwhite person working there. I answered him in front of the group, saying, “My parents were born in Bangladesh, I was born here in America.”

At that point, both the chaperone and the kids asked me where Bangladesh was located, and I told them it was in South Asia. Without missing a beat, the chaperone said, “But you’re too white to be Indian!” After laughing it off, he proceeded to do an impression of Apu, the convenience store owner from The Simpsons.

I stood there, shook and embarrassed as he continued to make the kids laugh with his impression.

What my experience demonstrates is how vulnerable we are to what Chimamanda Adichie calls, “the danger of a single story” (2009). The fact that being dark was synonymous with being Indian or how violence is synonymous with being Muslim (another stereotype I get often), shows how powerful these stereotypes truly are, especially if they are constantly reinforced and never corrected. It is 2021, and we are still misrepresenting people and their cultures based on our ideas of what we expect them to be. And perhaps we cannot take all the blame for believing in these generalizations and misrepresentations of people. However, we can choose to stop relying on one story to speak for many. If we do not broaden the scope of stories we tell and consume about other people and cultures, then we become part of the problem — the problem of telling a single story.

While stereotyping is, unfortunately, a common issue across many minority groups, it’s essential to create safe spaces where all people — especially youth of all identities and representations — can get to know each other better, face their biases, and learn more about themselves and how to take control of their stories and how they are told. As Adichie says, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not always that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story” (2009).

We thank you, Tabassam.

For More Information

Here are some additional resources you can use to increase your cultural sensitivity:

- Check out ACA’s Bullying Prevention Resources and the associated Tip sheet for Staff Training

- Visit Harvard University’s Project Implicit site for self-assessment and reflection through its Implicit Association Test (implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html)

- Read the Psychology Today blog post “The Sound of Racial Profiling: When language leads to discrimination” by Valerie Fridland, PhD (psychologytoday.com/us/blog/language-in-the-wild/202006/the-sound-racial-profiling)

- Read Articulate While Black: Barack Obama, Language, and Race in the U.S. by Geneva Smitherman and H. Samy Alim (goodreads.com/book/show/13690153-articulate-while-black)

- Watch Jamila Lyiscott’s TEDx Talk “Why English Class is Silencing Students of Color” (ted.com/talks/jamila_lyiscott_why_english_class_is_silencing_students_of_color)

Makela Elvy, M Ed, is an environmental educator and camp enthusiast. Along with Briana, she is also the co-founder of Smore Melanin — a platform dedicated to providing resources for BIPOC camp professionals. Over the course of her career, Makela has held camp positions ranging from head counselor to program manager. Her experience includes nature interpretation, curriculum development, and the creation of a 10-week venture program rooted in experiential learning.

Briana Mitchell has been a camp attendee since the age of six and a previous camp counselor and Teach for America Corps member. She is the director of AF Camp, a Change Summer camp, where she works to create high-quality summer opportunities for students that will increase their overall confidence, responsibility, curiosity, and independence. She is also the co-founder of Smore Melanin — a platform dedicated to providing resources for BIPOC camp professionals.

References

- Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story. TEDGlobal 2009. Retrieved from ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

- Arthur, C. (n.d.). The Cost of Code Switching | TEDxOrlando. Retrieved from youtube.com/watch?v=Bo3hRq2RnNI

- Brown, R. M. (2011) Starting from Starting from scratch: A different kind of writers’ manual. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

- Beukeboom, C. J., & Burgers, C. (2017). Linguistic bias. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.439

- Bhatia, T. K. (2018). Accent, intelligibility, mental health, and trauma. World Englishes, 37(3), 421-431. doi:10.1111/weng.12329

- Zeigler, K., & Camarota, S. (2019, October 29). 67.3 million in the United states spoke a foreign language at home in 2018. Retrieved from cis.org/Report/673-Million-United-States-Spoke-Foreign-Language-Home-2018#:~:text=In%202018%2C%20there%20were%2067.27,those%20who%20speak%20only%20English.