Camper behaviors can be tricky — especially in the post-COVID and digital age that we live in.

Kids have changed, parents have changed, and we have changed, resulting in more conscious care with how we approach these behaviors. This blog post aims at helping summer camp staff understand why campers might act the way they do, how they can work with campers through their behaviors, and tools to use in behavior improvement. This will help keep your campers, you, other staff, and the summer camp environment safe.

The first thing to know when dealing with campers and their behaviors is where they developmentally are and other circumstances that might be causing certain behaviors to happen. To help with this, here is a breakdown of the different developmental stages based on two developmental theories, as well as an explanation of other factors to think about when working with campers on their behaviors and giving tips during staff training.

Developmental Theories

Summer camp staff should know the different developmental stages of children and how these can affect their behaviors, emotions, and responses to their environments. Two developmental theories, those of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, can help with that understanding. Furthermore, combining the two theories can be helpful in your camp’s behavior-prevention and management strategies.

Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s theory on child development is a four-stage, universal approach based upon a child’s age. He believed that as children grow they become more aware of what is around them, and their brains grow accordingly. The four stages of Piaget’s theory are:

- Sensory, motor skills from birth to two years old

- Preoperational stage from two to seven years old

- Concrete operations from seven to eleven years old

- Formal operations from eleven years into adulthood (Main, 2021).

For purposes of summer camp, we will focus on the later three stages, as these are the ages primarily served in a camp setting.

In the preoperational stage (2–7 years old), Piaget believed that children lacked the ability to understand cause and effect or see other people’s perspectives (Main, 2021). This means one of your campers might not understand if you tell them not to jump in a puddle because you don’t want to take them back to the cabin to change their shoes. They will do it anyway because they don’t foresee the outcome of their decisions. This stage is the perfect time to start teaching natural consequences to help them make the connection. Maybe their consequence for jumping in the puddle is that they have to walk around with a wet shoe for 30 minutes until the next time you go to the cabin, instead of making a special trip.

The concrete operational stage (7–11 years old) is where children start to be able to solve problems and have full-length conversations (Main, 2021). At this stage, counselors might feel the need to help children solve their own problems rather than doing something for them. For example, a camper can’t find their sock and is blaming someone for taking it. A counselor might suggest that the camper go through their dirty clothes bag and check lost and found first — or maybe they never brought it in the first place. The counselor can ask the camper what a better solution might be for right now and guide them to the conclusion that maybe they can wear other socks today. Helping campers this age through their big emotions and to solve their own problems is a great solution to behaviors at this stage.

Lastly, in the formal operational stage (11 years +) children are still mastering the skills from their other developmental stages but add the ability to understand complex arguments (Main, 2021). It is important to note, too, that this is a very large age range, and an 11-year-old is going to be very different from a 17-year-old when doing activities together. This stage of development might bring more questions regarding what is happening around them and may usher in some teenage angst about even being at camp. Conversation-based behavior management at this stage works incredibly well, especially once you have created a relationship with your campers. Try talking out any issues that arise and giving your campers the tools they need to be successful while at camp.

Vygotsky’s Theory

Vygotsky’s theory follows a similar pattern to Piaget’s, as he understands children have to age in order for their brains to grow, but his theory is not so strict on age. He believed that children’s cultural development plays a role in their cognitive development. This leads children in different home or school environments to be at different developmental stages earlier or later than Piaget believed. To help with this more complex developmental range in groups of children, Vygotsky created his theory on Zones of Proximal Development, which scaffolds activities and skill abilities. The outer circle is the least amount of knowledge; a camper has never done an activity before or doesn’t know how. The next circle is that maybe they’ve seen someone else do the activity before and are familiar with it, but they need help to complete it from a mentor. The inner circle — that sweet spot we want all campers to achieve through activities we do at camp— is that after having been taught and helped with something, they can now do it on their own (Main, 2022).

With both of these theories, it is important to note that like Vygotsky said, each camper is different regardless of their age because of how they have been raised. A nine-year-old could already be in the formal operational stage, and a 14-year-old could be in the concrete operational stage. The job of summer camp staff is to scaffold activities to make an activity a little less challenging for some campers and to add a layer of complexity for others based on their needs in that space, like Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. For example, stepping in when a camper takes their shoes off on the soccer field and talking to them can help you both find a solution and make them feel their best at camp. Knowing the campers and building relationships with them is the best way to do this so we can mitigate camper outbursts and focus on the fun.

Behaviors at Camp

Now that we have addressed how different ages of campers behave at camp based on their cognitive development, we can talk about the nitty gritty of how to handle different kinds of behaviors while keeping those development stages in mind. This section aims to give you tools to use at camp to help with mitigation as well as the after effects of a behavioral outburst. Also note that behavior strategies can differ from camp to camp based on mission and values.

When dealing with kids having physical or verbal outbursts, fighting, or bullying, it is important to remember that there is probably something going on behind the scenes that needs to be addressed. Removing a camper from a situation is sometimes the best first step in order for them to calm down and be able to talk about what happened. Make sure counselors are able to use their preexisting relationships with kids to help them navigate through these situations before moving into the next step, which is how to prevent such situations from happening again.

Addressing Outbursts

Here are some great ways to address outburst behaviors and find solutions moving forward to keep kids at camp and keep everyone safe.

Behavior Contracts

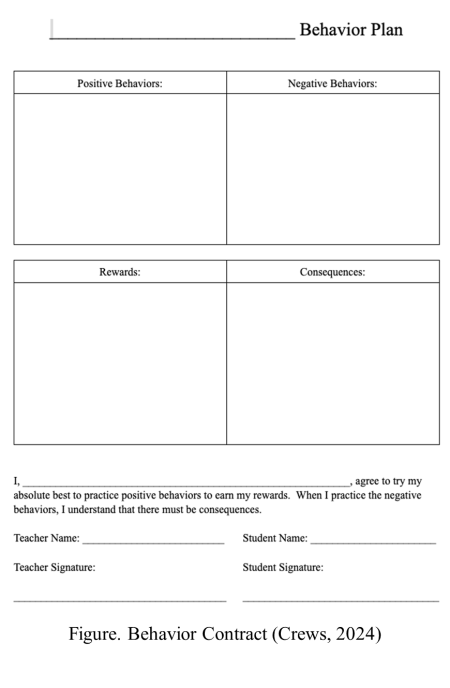

Behavior contracts, also known as behavior agreements, are highly effective tools for children of all developmental stages (see Figure). These agreements are collaboratively established between campers and counselors, outlining behaviors to avoid and behaviors to exhibit at camp, along with associated rewards and consequences. It is essential for this process to be camper-led, with counselors guiding campers to identify these categories. The agreement should include two to three behaviors and corresponding rewards/consequences for each section, starting with identifying the behaviors that led to the contract. Campers are then encouraged to consider opposite, kinder behaviors. Both parties should sign the contract to ensure mutual accountability, with the understanding that the agreement can be adjusted based on the camper’s progress. Consistency in applying rewards and consequences is crucial.

Implement a Reward System

Another strategy is to find a reward system that works for the camper. A common reward system camps use is beads. If a camper who is struggling with their behavior loves beads, assigning a special color just to that camper can be a prized reward when they achieve a behavioral goal. A reward should never be taken away once it has been given; this can be counterintuitive for a camper and cause the behaviors to avoid to become more prevalent. Use a consequence alongside the reward to continue encouraging campers to earn rewards instead of consequences.

Staff Training

Quality staff training will help to create an environment for positive youth engagement, which emulates the developmental theories we have talked about. Training should always go beyond compliance. Camps are typically required to train staff in things like CPR, first aid, mandated reporting, etc. Equipping staff with tools for behavior management is also a priority for most camps. If you don’t know how to positively engage with youth, how will everyone have a positive experience? There are endless training topics that you can potentially bring to your camp staff, and it can often feel overwhelming. Here are some practical questions to ask yourself as you work to prepare your camp staff for a summer full of camp magic.

1. What training already exists at my organization?

Make a list of trainings that you used last year and break them into categories. What aspects of your training plan fell into compliance (e.g., CPR, first aid, child abuse prevention)? What fell into youth engagement strategies (e.g., behavior management, games)? DEI? Mental and emotional health? Leadership? Don’t make any judgments just yet. Just organize your training plan into various buckets.

2. What patterns am I noticing with staff/youth engagement?

Now it’s time to review your camp data and look for trends. What are campers saying about their experience, their counselors, well-being, etc.? Review surveys and feedback from staff and parents/guardians. Even if you don’t send out surveys, review quotes you’ve collected or emails you’ve received. Think about situations that you’ve observed between campers and staff. Be aware of various biases that could skew your data — try to be as emotionally detached and logical as possible. This can be difficult to do when you love your camp and think everyone had an amazing experience.

When you’ve had the chance to review your data through an objective lens, write down the patterns. This is where you can focus your training. Maybe you notice that some of your staff get frustrated with a camper who “isn’t behaving well.” Maybe they need some more training in trauma-informed care. Perhaps that camper is showing signs of anger when they’re really feeling overwhelmed. Training your staff will give them the tools to ask themselves, “What deeper emotions lie beneath this behavior?” Behavior is communication, and your staff understanding this deeply is a key to a successful summer.

3. How will I incentivize my staff to participate?

How will you encourage your staff to take part in the training? Is it required or optional? Are your compliance trainings required but your behavior management trainings optional? Do you have the funds to pay your staff for training? Camps should always strive to ensure that staff are fairly compensated for their time, but sometimes the budget doesn’t have enough wiggle room. So what can you do if this is the case? Get creative. Can you provide meals during the training? Maybe a gift card or small stipend is possible. Can you provide training where a certificate is awarded? If you can provide youth workers with free (to them) training that comes with a certificate that will help them in other roles, that’s a big win.

4. Do I have to do it all at once?

No! It can be easy to look at your camp data and see many trainings that could improve your overall camp experience. But time and resources often force you to choose. Prioritize what needs to happen this summer, and build out your two- to three-year training plan with the rest. If you have returning staff, you can certainly build on their skills and knowledge over time.

As we have seen, camper behaviors are complex, and no one camper will behave exactly like another due to their cultural development and environments. By understanding how children develop and what is appropriate for their age level, we can train staff and practice quality behavior management strategies aimed at fostering a caring environment and giving kids an amazing summer at camp.

References

Main, P. (2021). Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development. Structural Learning.

Main, Paul. (2022). Vygotsky’s Theory. Structural Learning. structural-learning.com/post/vygotskys-theory

McKenna Crews is the university youth camp coordinator at Ball State University and has worked in summer camps, education, and out-of-school learning for eight years in several roles. She started her work as an overnight summer camp counselor and later became the leadership & development coordinator designing training for staff and counselors-in-training. McKenna graduated from Ball State University as a Social Studies Education major working in schools throughout her education. After graduation, she moved to Washington, DC, where she completed her master's degree at American University and worked as a summer day camp program manager and curriculum writer. She also taught middle school at Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia for two years. McKenna moved back to Muncie to take her current role managing the Indiana Youth Programs on Campus grant for the university overseeing three camps on her campus. McKenna believes every child deserves summer camp.

Jessica Stoltzfus is the associate director of camps administration at Butler University and has worked in youth summer camp programming and administration for over five years. She previously worked at the Butler Community Arts School where she managed 15+ summer youth music and arts camps. In her new role at Butler, Jess manages the Indiana Youth Programs on Campus (IYPC) grant from the Lilly Endowment and oversees camp operations for the University. In her spare time, Jess chairs the board of the Indianapolis Shakespeare Company, enjoys supporting local Indianapolis restaurants, and goes bouldering at her local gym.

Photo courtesy of Camp John Marc in Dallas, TX

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Camp Association or ACA employees.