Succession at summer camp can mean many things: succession of ownership, of leadership, or of culture. Of course, these may happen separately, in close proximity, or all at once. In any case, each can represent healthy change or unwanted conflict.

Succession Defined

While the term succession may suggest movement or action, the venerable Merriam-Webster dictionary reminds us it is a noun: person, place, or thing, such as the following (Merriam-Webster, 2020).

- The right of a person or line to succeed

- The act or process of one person’s taking the place of another in the enjoyment of or liability for rights or duties or both

- The act or process of a person’s becoming beneficially entitled to a property or property interest of a deceased person

- The continuance of corporate personality

- A number of persons or things that follow each other in sequence

- A group, type, or series that succeeds or displaces another

Yowza!

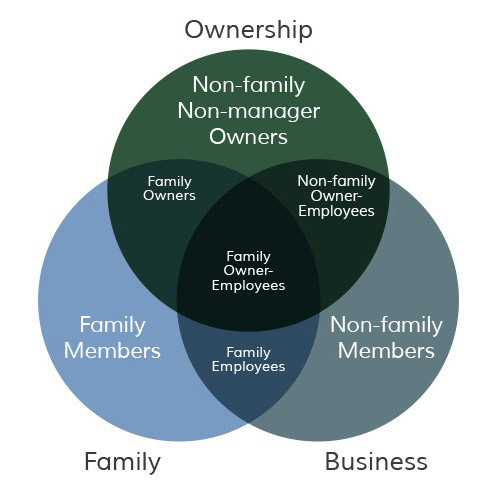

Adapted from Gersick, K., Lansberg, I., Davis, J., & McCollum, M., Generation to Generation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997; and Churchill, N., & Hatten, K., Non-Market-Based Transfers of Wealth and Power. American Journal of Small Business, 11(3), 1987, pp. 51–64.

Clearly, considerable overlap exists in the family, business, and ownership spheres. It is often difficult to separate what belongs in each of the circles. So, it is important to outline who has decision-making powers and what kind of decisions they should be involved in making.

Dan Michel, director of Brewster Day Camp (BDC) in Massachusetts, expounds on that last thought: “Be honest with yourself about your priorities and your view of the business.” He goes on to pose some critical questions: “Are you a family business or a business that you happen to run with your family members? Is the goal of the business to support the family, or is the goal of the family to support the business?” He adds, “Working in a family business, or working in a business with one’s family, can be a double-edged sword. For young people, this may present opportunities for growth and experience that they might not have elsewhere. On the flip side, it can be very easy to fall into established family dynamics and let your professionalism slip, creating difficult professional relationships and work environments.”

For those who own or direct camps, succession is perhaps more like an anomaly or deviation from the normal routines of camp life.

Leadership Transition

In his November 2019 article “The Big Missteps in Camp Leadership Transition,” Bob Ditter, a licensed clinical social worker and camp consultant, articulates some of the potential pitfalls in the succession-planning process.

Ditter’s five “big things” are:

- Waiting too long

- Assuming everyone is ready at the same time

- Underestimating family dynamics

- Underestimating camp “founder’s syndrome” (“the tendency of a person who has either founded a camp or has run one for seven years or more to hold onto their power or influence even after there has been a succession of leadership and they are no longer formally in charge”)

- Not having a transition or succession plan

To Ditter’s first point (waiting too long), succession plans should be in place long before they are needed. The actual plan will take at least three to five years to implement and approximately a year just to put together. Ideally, for a well-established camp, the plan should be designed at least 10 years before implementation and take into consideration emergency or unexpected situations such as death or incapacitation.

For her part, Milisa “Misa” Galazzi, the first full-time director of the BDC, says she would have liked to have had the time for her son Dan to work in another business before entering the family’s camp business, but the timing of her retirement didn’t allow her — or him — that luxury. Galazzi adds, “It can be hard to get out of a family business, so be careful getting in.” She advises family-owned camps to encourage new leaders to listen and learn, know their own strengths and weaknesses, and articulate how they can enhance the business.

Galazzi points out that when it comes to transition planning, “There’s no one size fits all,” positing, “It takes a lot of time, measured in years and decades, not meetings and minutes.” Successful planning, she says, also means respecting the process — and the older family members phasing out — as well as the psychological needs of all involved. Notably, she says family business can be tough because “members know all the skeletons in all of the closets.” She quotes Steve Sudduth, co-director of Wyonegonic Camps in Maine, as equating successful planning with good fiscal management of the assets of camp, including stewardship of the land.

The succession plan is a living document that may change over time. Like a strategic plan, it should be revisited every year to make sure it is inclusive of unanticipated situations and that the competitive and regulatory landscapes are taken into consideration on a regular basis.

At Cheley Colorado Camps, a key takeaway from their succession process was the importance of seeking broad consensus on the choice of a consultant. When they eventually chose that route, they experienced more success at handling “very difficult conversations,” according to current director Jeff Cheley. Again, a plan for succession is a living document subject to changes in direction.

Family Constitutions

A written plan is needed to detail how to include future family members and generations. As the generations grow, the number of children involved in the camp increases, and perhaps not everyone will have a role. Jobs and promotions should be planned in advance — what is available for family members and what they need to do to advance in position, so they are able to maintain the respect of others in the camp. It can prove disruptive to a camp community when a family member is promoted without merit. The metrics for promotion should be the same for everyone, be they family or not.

Ensure that family members (those who are active in the organization as well as those who are not) are part of regularly scheduled family meetings that reveal the state of the camp. Family members should also take part in putting together the articles of the family constitution. These constitutions should include such things as the family’s vision and values, employment policies, family development, and ownership policies (Poza, 2010).

That document will outline what family members must do to enter the company and move up the ladder. A sense of fairness is important so that nonfamily members do not feel that positions are simply handed to family members without being earned.

Cheley told us that what proved essential for him was a prior experience of working for another company before running his family’s business. “It’s important to know that all organizations face challenges,” said Cheley.

Some camps actually require work outside the business to learn important skills employees can later apply to camping, something Sudduth and his mother, Carol, spoke to during a transition-related meeting at the 2018 American Camp Association National Conference in Orlando, Florida.

Outgoing generations, Cheley advised, should pick a date to be done and allow those on the ascent to hire and train some of their own people.

Also of value is recognition that, as Ditter noted, in some cases, family members may not be ready to take the reins. It might be necessary to bring in an outsider to manage the camp until younger or less-experienced family members are ready to take over. Incentives need to be strong for nonfamily members so they realize they can keep their position as long as they perform well, not just until the next family member is ready to assume greater responsibility. Such staff may also take on the complicated role of mentoring young managers.

Galazzi notes the odd coexistence of first-generation ownership and third-generation leadership at BDC. She and Dan agree that their decision to use first names at camp, as opposed to familiar family monikers, is helpful in maintaining a professional environment and keeping business and personal issues separate.

Reflecting on work he has done in assisting camps with transition planning, Ditter concludes the following (2019):

. . . It has become clearer and clearer to me that most camp professionals don’t fully grasp the complexity of leadership transition and, consequently, make many mistakes that make the process more challenging and less successful. What do I mean by “less successful?” From my personal experience, “less successful” means when:

- Family members disown one another.

- The transition fails and new directors give up and leave.

- The culture at camp suffers and enrollment drops.

- Longtime, talented senior leaders who have been extremely loyal to the camp over the years leave because the environment during transition has become so acrimonious or destructive.

- In nonprofit agencies, longtime staff members of the camp refuse to embrace the new director and resist changes, even if their practices are detrimental to the children who attend.

Boards of Directors

Camp boards are often at the heart of succession planning and should be composed of family members and nonfamily members. Ideally, nonfamily members will outnumber family members so family ties do not taint decisions (Poza, 2010).

Likewise, it can be helpful to have such “outside” board members come from diverse backgrounds so they, too, are adding value to the oversight and management functions of the business. Like family board members, other board directors should have some working knowledge of summer camps, including the appropriate roles of a board member versus members of the actual leadership team. Failure to respect those distinctions can lead to disdain that often flows downward to counseling and instructional staffs and can be demoralizing for all.

In addition, board members or family members who simply “hang around” during the summer with no discernable role or responsibilities can pose an unnecessary distraction to those doing the hard work of running camp.

The Culture of Camp and Other Considerations

Keep close tabs on the camp’s culture, as that can be in transition too. When developing the succession plan, several factors should be taken into consideration.

- Maintain the culture of the organization. This is what people remember about being at camp and what motivates them to return. Sometimes, with a change in ownership or management, that culture can change. Be sure to reflect on and inventory what is unique and special about the camp so those qualities can be carried into the future.

- Take into consideration how painful change will be for your employees and customers. If the pain level is too high, the payoff may not be worth going through the transition.

- Remain alert to family dynamics and family skills. The children of camp leaders likely have been exposed to the family business their entire lives. They may have worked at camp since they were young and, over the years, have taken on renewed responsibilities. They are now experts in the field. But, in some cases, these same children may have poor management styles and may not be easy to work with. Weigh how necessary it is to have a family member at the helm if that person is going to cause conflict in the organization — and consider if that individual’s actions can be remedied through coaching or counseling. Personal conflicts sometimes take years to heal.

With regard to family members seeking a job or to move up in the business, Cheley said, “If joining the family business is not the best decision for the business and the child, the parent is the best person to help navigate this issue. It will be hard, but so is parenting.”

Respect for All

Because many family-owned camps are a mix of family members and nonfamily members, those in the latter category must be shown the same loyalty as those in the first. According to Galazzi, “Nonfamily members can be the difference between success and failure and should be treated with respect, thoughtfulness, and tenderness.” Such camp leaders can offer a different point of view, not typically being tied up in family dynamics. Trust, she says, is key.

Stuff Happens

It is useful to keep in mind that even the best-laid plans can go awry.

Commitments are made, marriages and divorces happen, career preferences change, natural disasters and pandemics occur. The point is things happen that may result in broken promises. Be sure to let younger generations know that, while you will do your best to groom them and secure a position for them in the organization, in the end you have to do what is best for the camp.

Cheley reminds us that “outside forces” — such as graduations, even deaths — can impact succession plans.

For Cheley, one poignant takeaway from the summer of 2020 and COVID-19 is that you can’t let your ego be wrapped up in success of the business. He said, “Everybody is struggling with fear and anxiety, and it’s important to separate one’s personal life from the family business.”

The Long Run

Long-term winners in the organized camp industry will be those who carefully construct and calibrate detailed, transparent plans for change and who, through thick and thin, remain highly focused on the needs of their customers: campers and their families.

Leann Mischel, PhD, is an associate professor at Coastal Carolina University. An expert in family business, she has served on boards of family businesses and businesses small and large. She has published widely in her field and has presented at conferences around the world. Leann also has experience as a camp director and camp consultant on succession planning. Her work has been recognized in Entrepreneurship Magazine, The New York Times, USA Today and the Wall Street Journal.

Stephen Gray Wallace, MS Ed, is an associate research professor and president and director of the Center for Adolescent Research and Education (CARE), a national collaborative of institutions and organizations committed to increasing favorable youth outcomes and reducing risk. He is a consultant to camps on staff training, teen leadership programming, outcomes measurement, and succession planning. He has broad experience as a camp director, school psychologist, and adolescent/family counselor. Stephen is a member of the professional development faculty at the American Academy of Family Physicians and American Camp Association and a parenting expert at kidsinthehouse.com, NBC News Learn, and WebMD. He is also an expert partner at RANE (Risk Assistance Network & Exchange) and was national chairman and chief executive officer at SADD for more than 15 years. Stephen is author of the books Reality Gap and IMPACT. Additional information about Stephen’s work can be found at StephenGrayWallace.com.

(c) Summit Communications Management Corporation 2020. All Rights Reserved.

Photo courtesy of West End House Girls Camp, Parsonsfield, Maine.

References

- Merriam-Webster. (2020). Succession. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/succession (29 July 2020).

- Ditter, B. (2019). The big missteps in camp leadership transition. Camping Magazine. November 2019. https://www.ACAcamps.org/resource-library/camping-magazine/big-missteps-camp-leadership-transition (29 July 2020).

- Poza, E.J. (2010). Family Business. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.