Across the country, summer camps are an integral part of children’s traditional summer experiences. Unfortunately, the same may not be true for children with disabilities. Representing only 3 percent of campers in one study of overnight summer camps across the United States (Laszlo Strategies, 2013), children with disabilities, just like their peers, should have opportunities to gain positive physical, emotional, and social outcomes from an inclusive camp experience (Schleien, Miller, Walton, Roth, & Tobin, 2017).

Increasingly, camp leaders are attempting to provide the support and accommodations needed for these campers to become part of the camp community. And literature is beginning to emerge on this important topic (e.g., special topic on “Inclusion” in Camping Magazine, Sept/Oct 2017). However, research efforts have not kept pace with the growing number of children with special needs who are attending or wish to attend summer camp. A recent study, described in the pages ahead, explored perceptions of social inclusion and engagement of campers with disabilities as conveyed by campers participating in a photography activity. Because this research focused on a summer camp where inclusion was a relatively new initiative, camp leaders were particularly interested in feedback to shape emerging inclusion efforts.

A small but growing body of research indicates the potential of inclusive camp experiences to promote a variety of positive physical, emotional, and social outcomes among those with and without disabilities (Gilmore, 2016). Though few studies address outcomes of the camp experience for campers with disabilities themselves (Schleien, Miller, Walton, & Roth, 2015), parents interviewed (Kopelowitz, 2013) reported that while their children with disabilities routinely faced boundaries with education, the camp experience provided them access to a sense of community. In addition, Kieval (2013) found an increased number of friendships made by campers with disabilities following participation in an inclusive camp program.

Improvements in an array of social skills and independence in activities of daily living were also reported, including positive outcomes in diverse areas such as:

- communication

- play behavior

- making choices

- cooperation

- taking responsibility

- independence

- self-esteem

- friendships (Arnold, Bourdeau, & Nagele, 2005)

Positive outcomes have also been documented for campers without disabilities as well as staff members. Most of those who have served as inclusive camp staff reported that their experiences with campers with disabilities led them to feel more comfortable with these individuals and more aware of issues related to disability (Singfer, Kress, & Uhrman, 2018). By getting to know their peers with disabilities, campers without disabilities learn to focus on capabilities rather than limitations, realize their commonalities, and diminish their fears (Blas, 2010). Staff and campers without disabilities reported that an inclusive program benefits the entire camp.

Methods

The study previously referenced used photography and accompanying verbal descriptions to explore campers’ conceptualizations of their camp experiences, with a specific focus on social inclusion. This method, which allowed for the examination of youth of varying abilities experiencing camp together, paid equal attention to reports from campers with and without disabilities.

The research took place at a residential camp located in the eastern US, serving approximately 500 campers by 150 staff. Of these campers, 15 were in the camp’s program for children with disabilities. A range of inclusion models are in place at overnight camps, and at this camp, multiple models ran simultaneously, providing options for those with different needs in terms of a “least restrictive environment.” Some campers were able to function, with the support of an aide, in the same bunk as their peers without disabilities. Campers in the program with whom we worked, however, lived in separate bunks and joined their peers without disabilities for multiple activities throughout the day. This program was only in its second year and considered by camp leadership to be the camp’s first formal foray into inclusion (with prior efforts being more episodic and informally developed). For reasons of confidentiality, we did not inquire about the specific classifications or diagnostic categories of participants with special needs. Overall, the campers represented a range of categories of disability, with the majority having been diagnosed on the autism spectrum.

Data Collection

The photography activity was introduced as an elective group activity. Seven pairs participated, with participants ranging in age from 15 to 19. Pairings of campers with and without disabilities proved helpful. The assistance provided by a peer without a disability could widen the range of youth with disabilities who were able to participate. Reciprocally, campers with a disability were noted to teach and support their peer partners without disabilities. The collaborations required by the participants in each pair fostered learning about one another and deepened relationships. These pairs did not have known relationships prior to camp other than perhaps being familiar faces from previous years. The partners jointly determined the subject or event to be photographed in response to the prompts provided. Discussions regarding the significance of each photograph encouraged individual input from all participants, allowing the exploration of the associations provided by every camper.

The camp inclusion coordinator and a member of her staff co-facilitated the activity. Prior to the program, researchers and camp personnel cooperatively developed these prompts:

- Show something you are really good at doing.

- Show something about camp that is meaningful or valuable to you.

- Show something that makes you feel connected at camp.

- If you could do one thing to make camp better for you, show what it would be.

Once photos were taken and discussed by the campers, activity leaders shared all photos and narratives with the research team. Following review, the research team communicated potential overall themes to the activity leaders, who then addressed proposed themes with the campers during a group meeting to confirm their relevance and suggest any necessary modifications. The research team was given this group feedback and revised themes accordingly. Final themes were shared and confirmed, with campers choosing photos that best represented each theme.

Data Analysis

Analytic methods drew from design thinking, which evolved as a combination of engineering and art, with more recent acclamation proposed by Burnett and Evans (2016) as a method in which a visual image of ideas may capture prevalence of thought as an approach to designing one’s life. Likewise, this visual mapping has been used to connect thoughts in a design format that enables a team to put themselves in the shoes of the individuals on whom research, a project, or innovation is focused. This Design Thinking Empathy Map (Crandall, 2010) technique involves creating a written map of ideas (i.e., what the individual of focus says, thinks, feels, and does) that connect to the individual who is drawn in the map’s center.

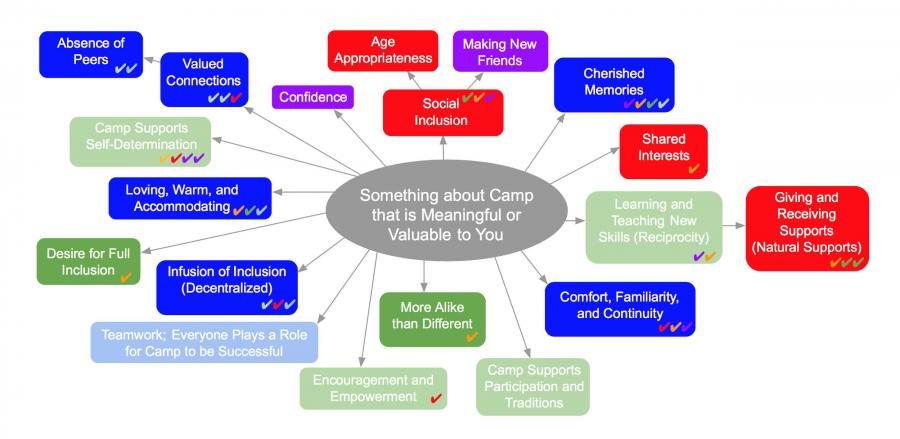

The research team created four design thinking maps, one for each of the four prompts, providing a visual representation of campers’ photographs and conversations. A sample design thinking map appears in Figure 1. Following this extensive review and interpretation of photographs and dialogue surrounding each of the prompts, the research team used the design maps and printed photos to collectively address the emergence of themes identified across prompts.

Findings

The subsequent analysis of empathy maps, using open coding of the narratives of campers with disabilities, led to the identification of three overall themes:

- Camp community and responsibility

- Experiences at camp

- Socialization and friendship

Camp Community and Responsibility

For campers with and without disabilities, comments such as, “I am part of a community at camp,” and “I enjoy being part of a community at camp” were frequently repeated in camper narratives. Photographs depicting campers participating in activities together, as well as comments regarding the support campers felt, clearly suggest a diverse, inclusive, and welcoming community. Telling quotations such as, “My friends help me walk back to my bunk at night when I can’t see,” and “They use my FM system to help me hear,” point to a strong sense of community and communal responsibility, in which friends working together help campers overcome environmental challenges.

Throughout their photographs and narratives, campers described a strong sense of connection to their peers and to the entire camp. These relationships, while powerful in and of themselves, were also understood as meaningful and authentic expressions of personal identities. Campers viewed “community” as a core value in their lives, and they were acutely aware of the uniqueness of camp in this regard. Particularly significant in their discussions was the focus on social inclusion. Regardless of their ability, campers relayed how welcomed they felt at camp by other campers and staff. They remarked on their responsibility in creating a socially inclusive community. This was not viewed as a burden, but rather appeared to come naturally, despite having no specific training or orientation to individuals with disabilities. When asked for specific examples of “including others,” campers readily replied with accommodations and strategies. The sense of “shared responsibility” was expressed by campers of all abilities.

Regarding campers with disabilities, the theme of camp community was connected to the significance of meaningful relationships with their peers of all abilities. They valued other campers because they believed they were being “treated as equals” and “could do normal things together.” Inclusive programs carry a risk of positioning individuals with disabilities in a passive role as recipients of assistance and providing negative messaging about disability as a deficit. These results, however, suggested they appreciated having something unique to offer, noting the many times they were able to help and teach others. Several examples of this reciprocity were evident in camper dialogue, and it appeared to serve as the foundation for true friendship between campers of varying abilities. Not only does inclusiveness appear to be a priority for camp and its campers, there is also a benefit to providing campers of varying abilities opportunities to demonstrate their own efficacy and value.

Experiences at Camp

The second theme revealed that campers connect to their camp through experiential and individualized approaches. Friday nights were described as significant for all campers for several reasons. This was one of the few occasions, outside of mealtimes, when the entire camp community joined together. Campers were generally with their bunkmates and other grade-level peers, but on Friday nights they were with their friends from across camp, offering opportunities to see friends of different ages, counselors from previous years, specialty staff, and camp leaders. Campers deeply valued the communal experience and found these camp-wide gatherings especially meaningful. As one camper with a disability shared, “On Friday evenings, I feel connected because I am with all my friends . . .. It feels good to share this with the rest of camp.” These sentiments were echoed in many of the narrative reflections.

Campers revealed the uniqueness of the camp experience and the difficulty of replicating it elsewhere. Campers without disabilities noted their experience at camp was “something you don’t really find anywhere else.” Campers explained, “At camp I feel connected, but at home, I don’t.”

Campers with disabilities expressed similar sentiments, often focusing on the specific elements of the specialized programs at camp that are not found at home. The intense, immersive connections they described at camp were apparently a unique phenomenon, separate from the less-favorable descriptions of their lives throughout the regular school year at home.

Socialization and Friendship

The final theme addressed the importance of peer socialization and friendship. While discussing their photos emanating from the prompt, “Show something at camp that is meaningful or valuable to you,” campers revealed the importance of friendships made during the summer. One camper explained that she took a photo of a particular camper because, “She is my friend and she makes me happy.” Campers enjoyed and preferred participating in activities with others. One camper with a disability highlighted the important feelings of normalcy that come along with socialization and friendships with peers without a disability. This camper explained, “She is a good friend because she doesn’t treat me like a baby.”

The importance of opportunities for socialization and friendship as meaningful and valuable camp qualities is highlighted in the design thinking map (Figure 1) that was created by the research team during the analysis. Within the map, camper pairs were color coded to reflect their ideas, including checkmarks next to those ideas that were reciprocated between pairs. These checkmarks demonstrated the most prominent and important aspects of socialization and friendships, including cherished memories; giving and receiving supports (natural supports); comfort, familiarity, and continuity; infusion of inclusion (decentralized); loving, warm, and accommodating; and social inclusion.

Discussion and Implications for Camp Professionals

Through the photography and discussion process, campers expressed the importance of camp community, responsibility, experiences at camp, socialization, and friendships. Their findings demonstrated how inclusive camps can work and the challenges they need to address. When the environment and programs are designed appropriately, successful inclusive experiences can flourish among campers of varying abilities. These findings also demonstrated how natural supports organically develop among campers when they are provided a welcoming and supportive environment.

Camp professionals could strive to embrace and fulfill these desires through facilitation of experiences that involve opportunities for the development of friendships. For example, these leaders could implement activities that involve cooperative participation and demonstration and discovery of shared interests among campers. Camp professionals who are seeking to lay the groundwork for meaningful social inclusion could pursue participatory opportunities that resemble this photography activity. The photography and discussion activity used in this study may have great utility for research and intervention within any camp setting. These activities tap into the perspectives of campers with and without disabilities regarding their experiences, desires, and needs. Providing opportunities and empowering campers in this manner could lead to a rich product of insight and energy to instigate changes toward meaningful social inclusion. The benefits of the inclusive camp movement appear to far outweigh the necessary efforts and costs, and camp professionals should continue to work together to make inclusive camp a common reality.

Photo courtesy of Camp Spearhead, Slater-Marietta, South Carolina

References

- Arnold, M., Bourdeau, V., & Nagele, J. (2005). Fun and friendship in the natural world: The impact of Oregon 4-H residential camping programs on girl and boy campers. Journal of Extension, 43(6), 1-11.

- Blas, H. I. (2010). Campers with developmental disabilities: The Tikvah program. In M. Cohen & J. S. Kress (Eds.), Ramah at 60: Impact and innovation (pp. 209–227). New York, NY: Jewish Theological Seminary.

- Burnett, W. & Evans, D. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Crandall, R. (2010, March 17). Empathy map. Retrieved from dschool-old.stanford.edu/groups/k12/wiki/3d994/empathy_map.html

- Gilmore, V. (2016, January). How special needs camping has impacted the camp experience. Retrieved June 22, 2016, from ACAcamps.org/resource-library/camping-magazine/how-special-needs-camping-has-impacted-camp-experience

- Kieval, D. J. S. (2013). Program evaluation of an inclusion program at an overnight summer camp. (Dissertation). Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

- Kopelowitz, E. (2013). The Impact of Ramah programs for children, teens, and young adults with disabilities. Retrieved from campramah.org/pdf/final_report_research_ramah_special_needs_programs_web.pdf

- Laszlo Strategies. (2013). Preliminary Research on Special Needs in Jewish Overnight Camp. Retrieved from jewishcamp.org/campopedia/preliminary-research-special-needs-jewish-overnight-camp/

- Schleien, S. J., Miller, K. D., Walton, G., & Roth, C. (2015). Evaluation of FJC Ruderman/Alexander inclusion initiative. Foundation for Jewish Camp. Retrieved from jewishcamp.org/knowledgecenter/evaluation-fjc-rudermanalexander-inclusion-initiative

- Schleien, S. J., Miller, K. D., Walton, G., Roth, C., & Tobin, L. (2017). Making summer camp a joyful place for everyone. Camping Magazine, 90(5), 23-24.

- Singfer, D., Kress, J. S., & Uhrman, A. L. (2018). Staffing Tikvah: Results of a survey of past Tikvah staff. New York, NY: William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education - JTS.

Lindsey Oakes, PhD, LRT/CTRS, is an assistant professor of therapeutic recreation in the Department of Health and Human Performance at Texas State University. She has also served as the coordinator for InFocus Advocacy, an organization that works with self-advocates, families, and community partners to enhance the image of people living with a disability. Self-advocates with disabilities help InFocus Advocacy prepare businesses and organizations on how to serve and accommodate people of all abilities, creating inclusive communities where everyone is welcome and valued.

Stuart J. Schleien, PhD, LRT/CTRS, CPRP, is a professor, chair, and graduate program director in the Department of Community and Therapeutic Recreation at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. He is also an executive director for InFocus Advocacy.

Jeffrey S. Kress, PhD, is an education researcher and consultant, and a faculty member at the William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education at the Jewish Theological Society.

Ginger Walton, MSN, RN, FNP, CNLCP is a consultant on the impact various disabilities have on the lives of individuals and their families. She is also a co-founder and executive director for InFocus Advocacy.

Abigail Uhrman, PhD, is an assistant professor of Jewish education in the William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education at the Jewish Theological Seminary.