Introduction

The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were particularly detrimental to the mental health and social functioning of children and adolescents.1,2,3 Recent studies have reported increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression along with a general worsening trend in youth mental health.4,5,6 These observations could be attributed to multiple pandemic-related factors specific to the experiences of youth, including: an increase in technology use, screen time, and media consumption, as youth spent more time on their computers when schools migrated to a virtual environment; and a decrease in activity choice, leading many young people to turn to social media for entertainment and social connection.7 Some researchers have hypothesized that more time online increased young people’s exposure to lugubrious or sensationalized media coverage of the pandemic, as well as the spreading of misinformation.8 Other quarantine-related factors that may have eroded young people’s mental health include social isolation, the closure of educational institutions, the confinement to homes, the disruption of normal routines, and increased parental stress.9 Some authors have noted that the closure of educational institutions created a lack of reassuring structure and removed what was a reliable support system for many children and adolescents. Moreover, the confinement to homes can lead to feelings of boredom and “cabin fever.”10 The disruption of normal routines may have created feelings of uneasiness, and may have hindered some young people’s ability to cope with stress and structure their days in productive, gratifying ways.11 Additionally, increased parental stress resulting from economic and health concerns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may have created a more stressful home environment for many youth.12 In pre-pandemic research, each of these factors has been shown to be correlated with increases in stress, depression, and anxiety.4

Research has also suggested that pandemic-related factors correlate with increased levels of several manifestations of depression and anxiety symptoms, compared to pre-pandemic levels. Specifically, compared to levels of anxiety and depression measured before the COVID-19 pandemic, youth assessed during the pandemic self-reported higher levels of depression, panic, somatic symptoms, generalized anxiety, and social anxiety. For males in particular, findings have suggested increased symptoms of depression, generalized anxiety, and social anxiety.13 For youth of all genders, COVID-19 life changes, infection concerns, school concerns, home confinement concerns, and basic needs concerns were most closely correlated with increases in depression and generalized anxiety, whereas infection concerns and school concerns were more specifically associated with increases in social anxiety.13

Given this constellation of increased distress and hypothesized pandemic-related causes, it is both logical and morally imperative to find accessible, inclusive, outdoor, socially immersive, physically healthy environments for young people. Traditional overnight camps are one such environment; one whose assets may serve as a therapeutic or corrective experience for young people. Traditional overnight summer camps contain a unique combination of elements that may help to mitigate negative mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Summer camps provide a hiatus from technology and screen use, and instead engage campers in constant physical activity in primarily outdoor spaces. Rather than a dependence on frequent parent interaction, summer camps promote self-sufficiency and independence. Campers are placed in a community setting where they must learn to effectively communicate, share, and co-exist with other campers of the same age. These problem-solving skills are developed and used without constant adult interaction. Summer camps provide campers with a largely new peer group, encouraging the formation of further friendships and social connections.14 Finally, summer camps provide a space where concepts such as fun and silliness are prioritized more than in a typical school setting. For some campers, summer camp provides an escape from the social pressures of their lives outside camp.15

In order to understand and summarize the association between overnight summer camp attendance and changes in young people’s levels of anxiety in published literature, a systematic review and meta-analysis were performed. A meta-analysis examines data from a number of independent, unrelated studies with similar samples with the objective of determining general trends for that sample. The aim of this meta-analysis was to aggregate data examining overnight summer camp attendance and changes in young people’s levels of anxiety as measured in pre-pandemic empirical studies. It is hypothesized that young people attending overnight summer camp will self-report lower levels of anxiety immediately after their camp stays, relative to their pre-camp self-reports, on psychometrically sound questionnaires.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed using PubMed, PubPsych, Google Scholar, and the research bibliographies of the American Camping Association and Canadian Camping Association using the keywords “summer camp,” “camp,” and “anxiety.” Articles were examined against inclusion and exclusion criteria listed below at stages by title, abstract review, and full-text review.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Empirical studies, written in the English language, in peer-reviewed journals that included a quantitative analysis of psychological and/or psychosocial effects of participation in overnight summer camp programs

- Longitudinal studies that measured constructs before and after camp

- Use of at least one valid and reliable self-report measure of anxiety

Exclusion Criteria:

- Studies conducted at day, rather than overnight/residential camps

- Insufficient data provided to view or calculate the mean and standard deviation of self-reported anxiety scores

The online search of social science journal databases originally yielded 15 articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria. Seven were excluded, based on one or both exclusion criteria, yielding eight studies for the meta-analysis (Table 1.). In instances where standard deviation was not explicitly reported in the study, an average standard deviation of pre- and post-camp anxiety scores was estimated using corresponding t-values from p-values provided within the article. This value was then converted to standard deviation using the following relationships:

- Standard Error = Mean Difference / t-value

- Standard Deviation = Standard Error

(where N is sample of campers used for pre- and post-camp anxiety measures)/li>

(where N is sample of campers used for pre- and post-camp anxiety measures)/li>

In instances where articles reported separate values for state and trait anxiety as part of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC), the two scores were averaged to be used as a mean anxiety score. Statistical meta-analysis by random model was performed through SPSS using Cohen’s d as an effect size measurement and an inverse-variance risk for continuous data. Cohen’s d as an effect size describes the overlap between two samples in order to quantify an average distance between the two groups. In the instance of this meta-analysis, the two samples are pre-camp anxiety scores and post-camp anxiety scores, and the effect size represents the average difference between them.

Table 1. General Characteristics of Studies Included in Meta-Analysis

|

Authors & Year |

Sample |

Length of Camp |

Camp Characteristics |

Anxiety Scale Used |

|

Briery & Rabian, 1999 |

90 children (boys and girls), ages 6-16 |

1 week |

Each camper was attending a camp that met their specific physical needs (asthma, diabetes, spina bifida) |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) |

|

Bultas et al., 2013 |

49 children (boys and girls), ages 8-15 |

5 days |

A pediatric cardiac camp designed for children with heart disease |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) |

|

Kiernan et al., 2004 |

119 children (boys and girls), ages 7-16 |

10 days |

A therapeutic recreation camping program in Ireland for European children with chronic illnesses. |

The Physiological Hyperarousal and Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children (PH-PANAS-C) |

|

Anarte et al., 2020 |

20 children (boys and girls), ages 8-14 |

10 days |

The summer camp located in Spain, specialized for campers with type 1 diabetes, includes educational activities and circuits along side traditional camp activities. |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) |

|

Feltis, 2020 |

169 campers (boys and girls), ages 6-15 |

6 days |

Traditional overnight camp in Southwestern Ontario. |

Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) |

|

Simons et al., 2007 |

29 children (boys and girls), ages 8-17 |

5 days |

A camp designed for children with complex cardiac defects included a combination educational programming and enjoyable camp activities. |

The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) |

|

Gant, 2009 |

53 campers (male and female), ages 6-21 |

1 week |

The camp is designed for campers with muscular dystrophy with activities adapted to abilities of the children. |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) |

|

Rawson & Barnett, 1993 |

191 campers (boys and girls), ages 8-12 |

10 days |

A residential therapeutic camp specifically designed for children with severe emotional disorders. Includes traditional camp activities and programming that incorporate behavior modification techniques |

The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) |

Results

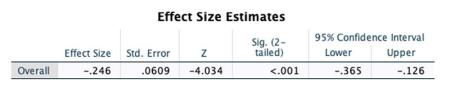

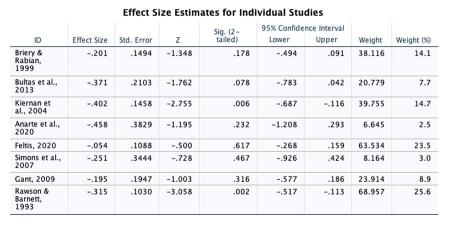

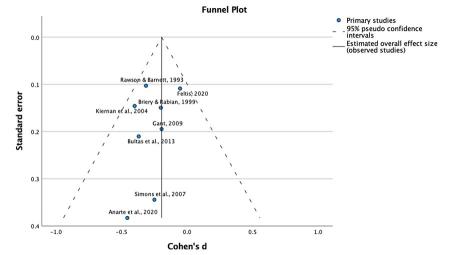

The means and standard deviations of participants’ (n=720; age range 6-21 years) self-reported pre-camp and post-camp anxiety scores were aggregated for meta-analysis. Results of the statistical meta-analysis are presented in Table 2., Table 3., and Fig 1. Calculations of overall effect size (Table 2.) yielded a statistically significant decrease in anxiety symptoms post-camp compared to pre-camp with a Cohen’s d of -0.246 (95% CI -.365 to -.126, p < .001). Calculations of effect size of individual studies (Table 3.) show an average decrease in anxiety symptoms of campers at each of the summer camps included in the analysis. Statistical significance varied between summer camps, and weight percentage of overall effect size is shown based on the sample size of each study. The funnel plot (Figure 1.) shows the overall effect size measurements in comparison to each individual study, plotted by effect size and standard error. Confidence limits of overall effect size are represented by the dotted lines. As effect size is an estimate rather than an exact value, the confidence interval represents the upper and lower bounds that the effect size lies between with a probability of 95%.

Table 2. Overall Effect Size Estimates

Table 3. Effect Size Estimates for Individual Studies

Figure 1. Funnel Plot of Overall and Individual Effect Size Estimates

Effect size is a representation of the change in average scores in self-report anxiety measures post-camp compared to pre-camp. Calculation of Cohen’s d (Table 2.), the chosen measure of effect size, suggested that participants experienced a small- to medium-size decrease in the intensity of their anxiety over the time they were at overnight summer camp (d = .25; SE = .06, p < .001). Furthermore, when separated by individual study (Table 3.), each article was calculated as having a negative effect size with varied magnitudes. As shown in the funnel plot (Fig 1.), each study falls within the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

These findings are especially meaningful from a public health perspective, given that the camps in the study, like the estimated 7000 in the US, offer experiences that last just a few weeks, are less expensive than inpatient or outpatient treatment for anxiety, do not carry any stigma associated with mental health care, and are accessible to a wide range of young people. The increase in post-pandemic mental health symptoms in children and adolescents has prompted the search for additional support. This meta-analysis offers the first summative evidence that participation in traditional overnight summer camps has anxiolytic benefits for young people. As such, camps are promising milieus for population-wide treatment of young people’s increased anxiety, whether or not its etiology is pandemic-related.

A Cohen’s d value of 0.25 is a small to medium effect size, with a clinical significance that translates to approximately 60% of post-camp anxiety scores being lower than pre-camp anxiety scores. The negative valence of each study’s effect suggests that camp stays are associated with a reduction in anxiety; the variable magnitude of each study’s effect suggests the need to better understand which factors – perhaps prominent in certain camps – are associated with stronger anxiolytic benefits. Furthermore, each effect size falls within the 95% confidence interval of the overall effect size, suggesting negligible publication bias.

Limitations

Six of the eight camps (80%) that met criteria for this meta-analysis served youth with specific medical needs. These camps included on-site, specialized staff trained to respond to the physical challenges the campers were facing in addition to general counselors and camp staff. Furthermore, these camps included physical, educational, and group bonding activities along with emotional exercises intended to boost the self-confidence of campers and to increase the comfortability of living with that particular medical condition. In some instances, these guided exercises included forms of cognitive-behavioral therapy. On the surface, these camps may seem like separate entities to traditional summer camps without a specific camper population, however, these camps still include the same combination of characteristics unique to all summer camps, thus expanding the results seen at these specialized camps to be applicable to campers at all summer camps. Further research comparing the effects of cognitive-behavioral treatments conducted in traditional, clinical settings to the effects of these treatments administered in a camp setting could help to distinguish whether elements of summer camp or the psychological therapies were more consequential to the observed decreases in anxiety.

While the speciality camps included programming specific to the medical needs of the camper population, the offerings of activities at all eight camps mirrored those at camps who serve medically typical children. Each camp used recreational activities designed to keep the campers physically active, take advantage of the natural setting, and promote a fun and carefree atmosphere. Furthermore, while the specific techniques and exercises facilitated by the staff of the speciality camps were led with the hope of effecting the campers’ perceptions of their own medical condition, all camp staff learn and utilize forms of cognitive-behavioral therapy whether it be learning to appropriately identify and treat homesickness or simply engaging a camper in an activity. Regardless of the intention of these trainings and exercises, the strategies used by camp staff are widespread. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the staff support, friendship opportunities, adventuresome activities, and sense of belonging were representative of those in larger, national studies of the benefits of summer camp. Regardless of its mission and participant demographics, high-quality summer camps share a uniquely beneficial combination of four factors: Community Living; Away from Home; a Natural Outdoor Setting; and Recreational Activities. This study provides evidence that this combination diminishes young people’s symptoms of anxiety.

While the results should be considered applicable to all summer camps, this meta-analysis included only eight qualifying studies, six of which were medical specialty camps, thus limiting its generalizability. More research is needed, at other overnight camps, with an even more diverse group of youth. Additionally, to solidify summer camps as potential sources of support for children and adolescents following the COVID-19 pandemic, studies must be conducted on how pandemic related factors have changed or shifted the landscape of campers at summer camp. It is possible that due to the pandemic-related factors, children and adolescents experience new needs and challenges. As the data from the eight studies were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic, these needs and challenges may differ from the campers represented in this meta-analysis. Future studies should also explore the association between camp and other social-emotional constructs such as depression and self-confidence.

Conclusion

This study provides the first preliminary evidence that overnight summer camps—including those with and without specific treatments for anxiety, and youth with and without diagnosed behavioral and emotional concerns—are associated with a reduction in self-reported anxiety. Therefore, they should be considered a promising environment for combatting the increase in anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents following the COVID-19 pandemic.

About the Author

Zach Trotzky graduated from Georgetown University in May, 2022 with a Bachelor’s Degree in Human Science. During his undergraduate education, he participated in multiple global health research projects including those tracking and analyzing the COVID-19 pandemic. He began research on summer camp during the summer before his senior year. Starting this fall, Zach will be working as a research assistant at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. This summer, Zach will be working at Camp Belknap, located in Tuftonboro, New Hampshire, as Division Head of the Cadet division. Including his time as a camper, this will be Zach’s twelfth consecutive summer returning to Camp Belknap. His overwhelmingly positive experiences at summer camp are what motivated him to conduct independent summer camp research.

References

- Xiang, M., Zhang, Z., & Kuwahara, K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 63(4), 531.

- O’Sullivan, K., Clark, S., McGrane, A., Rock, N., Burke, L., Boyle, N., ... & Marshall, K. (2021). A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1062.

- Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of affective disorders, 275, 112-118.

- Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., ... & Snell, G. (2021). Mental health impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on children and youth–a systematic review. Child and adolescent mental health.

- Liang, L., Ren, H., Cao, R., Hu, Y., Qin, Z., Li, C., & Mei, S. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric quarterly, 91(3), 841-852.

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Schlack, R., & Otto, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 1-11.

- Tso, W. W., Wong, R. S., Tung, K. T., Rao, N., Fu, K. W., Yam, J. C., ... & Wong, I. C. (2020). Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 1-16.

- Imran, N., Zeshan, M., & Pervaiz, Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 36(COVID19-S4), S67.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 1). Helping children cope with emergencies. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/childrenindisasters/helping-children-cope.html.

- Estacio, R. D., Lumibao, D. D., Reyes, E. A. S., & Avila, M. O. (2020). Gender difference in self reported symptoms of cabin fever among Quezon city university students during the Covid19 pandemic.

- Singh, S., Roy, M. D., Sinha, C. P. T. M. K., Parveen, C. P. T. M. S., Sharma, C. P. T. G., & Joshi, C. P. T. G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry research, 113429.

- Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., Chang, O. D., & Downing, K. M. (2021). Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105585.

- Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. D. (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1-9.

- Shafer, L. (2016, July 1). Lessons from camp. Harvard Graduate School of Education. Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/16/07/lessons-camp.

- Laliberte, J. D. (2019, November 4). Crafting healthy conceptions of masculinity: What the summer camp experience can provide for boys. Camping Magazine. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://www.acacamps.org/resource-library/camping-magazine/crafting-hea….

Appendix

Table 4. Means, Standard Deviations, and Sample Size of Individual Studies

|

Article |

Npre |

Mpre |

SDpre |

Npost |

Mpost |

SDpost |

|

Briery & Rabian, 1999 |

90 |

34.992 |

7.49 |

90 |

33.439 |

7.924 |

|

Bultas et al., 2013 |

46 |

28.13 |

3.845 |

46 |

26.705 |

3.845 |

|

Kiernan et al., 2004 |

96 |

1.46 |

0.249 |

96 |

1.36 |

0.249 |

|

Anarte et al., 2020 |

14 |

32.903 |

20.974 |

14 |

22.665 |

23.687 |

|

Feltis, 2020 |

169 |

24.37 |

8.46 |

169 |

23.91 |

8.46 |

|

Simons et al., 2007 |

29 |

12 |

7 |

12 |

10.3 |

6.2 |

|

Gant, 2009 |

53 |

27.64 |

4.09 |

53 |

26.77 |

4.79 |

|

Rawson & Barnett, 1993 |

191 |

12.22 |

6.4 |

191 |

10.06 |

7.29 |