Like many of you, I spent last summer monitoring social media for information about how the camps in my home state of Missouri were handling the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the social nature of camps — many people in close proximity to one another — I was worried about how they would be able to make it through the summer without an outbreak.

My work in emergency management started when I was a camp counselor, coordinating campsite evacuations and managing storm shelters during tornado watches. As I got older, I moved to working as our camp’s standards coordinator. Now I teach and study emergency management, working with students who go on to be emergency planners, nonprofit directors, and recreation facility coordinators. The pandemic brought together my love of camps and my profession. As the pandemic picked up steam, I was on the phone with our other area camps talking through our options, revising emergency plans, and making the tough decision that all of us faced.

Many camps made the difficult decision to close, citing a lack of resources or the inability to be flexible enough to adapt to the changes needed for their campers to have a safe summer. Others shifted their programming to incorporate social distancing and amped up their cleaning and wellness strategies. Some took a calculated risk to open. Although they knew they could not entirely eliminate the threat of COVID-19, their camp would not survive without their usual summer revenue. Every organization did what they felt was best to protect their campers and staff while also looking out for the future of their camps.

In short, we see what usually happens during times of disaster; folks did what they could with the resources they had available. Still, it was no surprise when the first few news stories rolled in announcing some camps were closing sessions early or ending the summer entirely.

Many camps that did open hedged their bets by undertaking rigorous, and often expensive, efforts to adapt to our new reality. Camps were given roughly four months to reengineer their entire programs to meet a set of ever-changing guidelines that were not even designed for their specific needs, but rather schools and day cares. The amount of work was monumental, and the urgency with which they needed to implement the changes was grueling.

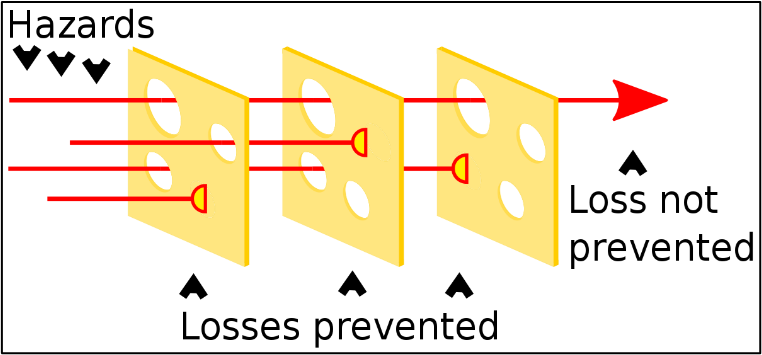

As camps, we can only control a portion of the risk. While we can significantly reduce the risk of COVID-19 through prevention measures, we can never eliminate that risk entirely. In my day job teaching emergency management, we have what we call the Swiss Cheese model of risk. If every prevention effort you put in place is a slice of swiss cheese, the holes represent a mistake or a gap in coverage. You create paperwork, but someone might forget to turn it in. You have a process in place, but a counselor may get distracted and skip a step. We know that mistakes happen, so we have multiple prevention efforts in place. But when multiple gaps in coverage line up, that is when a failure in the system occurs.

Some camps this summer had a long list of measures in place. They:

- Tested campers and had repeat physicals upon arrival

- Took temperatures each morning

- Mandated masks

- Eliminated as many common spaces as possible to minimize exposure

- Followed strict processes for quarantining patients

Yet, even with such careful actions, camps still had individuals test positive.

Those camps that made it through the summer without any cases had one very important thing in common: they were lucky.

By lucky I mean that the highly likely event of a positive case just hadn’t happened yet. Luck is the colloquial way of saying likelihood, changed so that we can tell ourselves there was nothing we could do about it. Similar to hope, luck is neither a strategy nor a course of action. When it comes to the hard data of risk management, the only way we can truly reduce our risk is through preventative actions, with every action taken gradually decreasing our risk.

Taking these preventative actions is not always easy. With COVID-19, the deck was stacked against us. Camps are social by nature. The first thing on every camp’s website is that classic photo of a circle of happy kids, arm in arm, enjoying the spectacular program the staff offers. How do you take that experience and remove the hands-on team building, the high fives from counselors, and the hugs at the end of a session? How do you make sure a camper gets the life-changing experience camps strive for while telling them to keep their distance from others?

Simply put, there are things we cannot control. We cannot control whether our campers follow our suggested quarantine before they arrive. We cannot control the honesty, or lack thereof, on a self-report survey about symptoms. We cannot control the regulations our area’s government bodies put in place. We cannot control their individual actions; we can only control our facility’s response.

As we look to next summer, a number of new developments may work in our favor. First, we will have an entire year’s worth of data, scientific research, and better-developed guiding documents.

In March, I found myself frantically searching for guidance on how to help my camp prepare for the summer. The best I could find was a pink eye containment plan from a neighboring facility — not exactly a solution for a global pandemic. By early summer there was still very little information out there, and even less that was specific to camps. Now, thanks to the efforts of the American Camp Association and the YMCA of the USA, we now have the Field Guide for Camps on Implementation of CDC Guidance, a critical document to have read as you make adjustments for next summer.

What we know about COVID-19 continues to be refined by researchers. As we started the 2020 season the numbers were all over the board, with confusion over the length of time the virus could live on surfaces and estimates ranging anywhere from hours to weeks depending on the environment. Scientists now have had time to study the virus and are able to give more specific information about how it is spread. As we move to the 2021 camp season, the specificity of this information will continue to grow.

Our campers and families will also have had a year to adjust to our new reality. When the pandemic began, many school districts simply closed for the remainder of the year, making our camps the testing ground for the “new normal.” Campers were having to undergo a rough transition from their regular lives of school and socializing to a foreign environment of masks and social distancing. Now many schools have taken the same precautions your organizations did this summer, so next summer these behaviors should be more engrained in the culture.

We also have some new resources in our toolbox, and new approaches that schools and organizations are refining during the academic year:

- Cohort-based planning — Schools are arranging classes to keep individuals in modular groups that are siloed from other cohorts. If done correctly, this will minimize those exposed to the cohort and their assigned staff members should there be an outbreak. The key here is making sure that any camp-wide staff (food service, ranger, facilities) do not come in contact with campers, as they could easily be the carrier from cohort to cohort. This was an important lesson that many skilled nursing facilities learned over the spring and summer months. If your facility has employees who regularly make the rounds to see all groups or individuals at the facility, they can also be the quickest method of exposure to the virus.

- Open access trainings — While the specific needs of your organization vary according to size and type of program you offer, without a doubt there are relevant trainings freely accessible to you right now. Sources including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Johns Hopkins University are constantly rolling out new guides and trainings focused on specific tasks that your organization may be carrying out. While less relevant to smaller organizations, large camps could certainly benefit from the Johns Hopkins Contact Tracing Course. This training has become the foundation of many organizations’ COVID-19 response efforts. At a more basic level, the CDC offers countless videos, information sheets, and resources for all types of organizations, including suggestions for youth and summer camps.

- New studies and lessons learned — As we continue through the academic year and get closer to next summer, we will see more stories pop up with “lessons learned” about how to manage COVID-19. Be sure to follow news stories about facilities similar to yours. Learning from others’ experience is useful. What happened at their facility, and could it happen to yours? What new approaches are facilities taking that you could adopt at your camp? What are the weak spots in your organization’s armor, and how are other places fixing it?

- ACA webinars, conferences, and publications — If you are reading this you have a strong supporter in your corner. As the pandemic gained momentum last spring, ACA immediately began offering webinars with some of the top experts in the country. These webinars covered a wide range of topics including public health and hygiene, employment law, emergency planning, and international visas. As we get closer to the 2021 camp season, keep an eye out for additional ACA webinars.

These resources are great, but they will not protect your camp unless you use them! You — as camp directors, as staff, as stakeholders in your camp — need to take action now. Use this off-season to address what might be the most important tool in your toolbox: your camp’s emergency plan. Engage your key staff members and your local stakeholders and identify what to do if and when your camp sees a positive COVID-19 case next summer. What elements did not work this summer? What challenges did you face that you had not accounted for? Engage your stakeholders, revise your plan, and run drills of that plan to make sure your camp can do what it needs to when the time comes. Now is the time to get started. Remember, it is planning and preparation, not luck, that will get you through next summer.

John Carr, MS, is an emergency planner and educator from Maryville, Missouri. He serves as Emergency and Disaster Management program coordinator at Northwest Missouri State University, teaching courses related to emergency management and facility emergency planning. Carr also serves as director for the Center for Camp Safety and Emergency Preparedness, developing research and publications for camps across the country. For more information on the Center and their emergency planning resources, go to ReadyCamp.org.