Hi Camp Pros!

I’m so excited that you’re with me reading this blog. As I’ve mentioned before, one of my goals is to be an integral part of knowledge translation for researchers and camp professionals. This should be a reciprocal relationship! What researchers do and find is important for applied practitioners and camp professionals – your campers, programs, and outcomes are what fuels research. We must work together to progress the camp industry forward and improve experiences for youth.

As the title of this blog shows, this piece is about how to read and implement quantitative research in your programs. If you’re interested only in reading about this type of research, that’s great! However; if you also want to read about qualitative research (research done with words instead of numbers) and how to implement it in your camp, make sure you check out my last blog. Some of the information in each piece may be similar — for example, how to access articles online and reading the abstract and introduction — and some may be very different, like judging the quality of research and reading the results. Keep in mind, Laurie Browne also wrote a piece on “geek speak” and understanding research. All together, these blogs will give you a good overview of how to use research in your work.

Okay – let’s get into it! For the purposes of this blog, I will follow along with the same steps as I did for my previous piece about reading qualitative research.

Step One: Find the Article

Many research papers are available online through open access journals, while readers are required to pay for some others. My preferred search method is using Google Scholar. Simply go to the site, type in the title of the journal article or search terms with quotations around multiple words in a term (e.g. “summer camp”) and see what comes up. This way, you can find a lot of different types of articles. If you are looking for a specific article and it doesn’t come up when you type it in Google Scholar, try searching the journal it was published in. Some journals have databases with archived issues, so try going to the journal website and search by volume and issue.

A typical article cited in APA format looks like this:

Author(s) (year published). Title of article. Journal name, volume(issue), page numbers if published in print. DOI.

These steps of reading and applying research will make more sense if we follow along with an example paper. Let’s try finding an article published by Barry Garst and Ryan Gagnon of Clemson University, and Anja Whittington, from Radford University. The citation is below:

Garst, B.A., Gagnon, R.J., & Whittington, A. (2016). A closer look at the camp experience: Examining relationships between life skills, elements of positive youth development, and antecedents of change among camp alumni. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 8(2), 180-199. doi:10.18666/JOREL-2016-V8-I1-7694

If you go to Google Scholar and enter the title “A Closer Look at the Camp Experience: Examining Relationships Between Life Skills, Elements of Positive Youth Development, and Antecedents of Change Among Camp Alumni,” it’s the only result that comes up. Sometimes when a reader clicks on the title, it will take you to the journal website with the abstract; however, when we click on this title, the link opens the pdf file – perfect!

Step Two: Look at the Abstract

The abstract is always found at the beginning of the article. Reading the abstract will allow the reader to decide if he/she wants to move forward and read the entire article. Typically, it provides a lot of great information, including the topic of study, a bit of a literature review, the aim or purpose of the study, information about methods and participants, results, and discussion of the findings. After going through the abstract, the reader should have enough information to determine if he/she wants to invest the time to read the entire study and if it will be interesting and applicable to their field of study/work.

Let’s take a look at the example article. The first line discusses the overall topic of study: program components that contribute to positive outcomes for campers. There were two purposes of the current study. First, “to develop reliable and valid measures of life skill development, elements of positive youth development (PYD), and antecedents of change within the context of camp” (Garst, Gagnon, & Whittington, 2016, p. 180). Secondly, “to examine potential relationships between life skill development, elements of PYD, and antecedents of change to better understand elements that influence youth outcomes in camp” (p. 180). So overall, the goal was to develop a survey, questionnaire, or some sort of tool to assess whatever it is that may have led to positive outcomes for kids at camp, and also to understand how these elements that brought about the change, interact. Cool. The researchers collected data from 429 camp alumni through an online survey and then did some fancy analyses to figure out how the different variables interacted, leading to participants’ scores. From the results they developed three tools, but they don’t tell us what they are. Oh, cliffhanger! I’m reading the whole study!

If this doesn’t sound interesting or valuable to you, just stop here. Take a look at the list of camp-related studies that the ACA complied, choose another one to read, and start again at step one. If, on the other hand, you want to continue reading this paper, let’s move to step three.

Step Three: Read the Introduction

The introduction serves a few different purposes. It sets up the rest of the paper and explains why the current study is taking place, as it provides good evidence for what studies have been done in the past that relate to the current purpose, and in particular, what’s missing from the field of study. In addition, it also provides a great overview of theories that inform the topic of interest, work that has been done with the same or similar population (participants), or in the same environment. I really enjoy reading introduction sections and literature reviews as they often cite other studies that I would find very interesting.

The current paper gives a very detailed introduction and literature review. It begins with some general information about camp and the need for the creation of instruments to “measure mechanisms of change” (p. 181). The final sentence of the introduction reinforces the purpose(s) of the study: to develop instruments to measure life skill development, elements of PYD, and antecedents of change at camp, and to examine the interaction of these three elements that may contribute to positive outcomes for youth at camp.

Following the purpose statement there are individual literature reviews on the three elements: life skill development at camp, positive youth development, and antecedents of change.

Take a look this section I captured from the life skill development review.

The second sentence lists seven different life skills or program outcomes, including: socioemotional developmental outcomes, career development, health and physical activity outcomes, learning and academic outcomes, environmental awareness, resilience, and social-cultural understanding. If you were interested in any of these outcomes and how they manifested at camp, you could follow the corresponding citations and return to step one, to search those studies.

Let’s look at the first citation for socioemotional development: Henderson, Bialeschki, Scanlin, Thurber, et al., 2007. Go to the reference section of the paper and see if you can find this study. There it is.

If you thought this would be an interesting paper to read, you could search the title (Components of camp experiences for positive youth development) on Google Scholar and see what comes up. Pretty cool don’t you think?

Step Four: Check out the Methods

If it was yet to be discussed, the methods section will explain whether the study is qualitative or quantitative, it’s design, participants, data collection, and forms of analysis. Often times qualitative studies are easier to follow along with. If you’re interested in learning a bit more about qualitative papers, take a look at my previous blog post.

As for quantitative studies, sometimes this can be difficult to understand since fancy terms are used (e.g. longitudinal, correlational, ANOVA, MANOVA, multiple regression model, etc.). If you don’t understand what these terms mean, don’t worry! Either skip ahead to the discussion section, since the results will likely focus on these types of tests and their corresponding results, or see if your favorite search engine can help you understand them.

Quality of the study is important to discuss. Again, Laurie Browne wrote a blog that includes a discussion of bias, which may impact a study’s quality. See that blog here (https://www.acacamps.org/news-publications/blogs/research-360/research-360-crash-course-geek-speak). In addition, for quantitative studies terms such as reliability and validity will often be discussed. Reliability refers to how replicable the results are using a given test or instrument (for example, a Quality of Life (QoL) test). If someone took the same QoL test repeatedly, would their results be mostly the same? Validity determines whether a test/instrument measures what it is supposed to be measuring. Following the QoL example, are the questions or measures determining quality of life, or enjoyment of life? Although these may seem like similar concepts, quality of life and enjoyment of life may be very different. Most quantitative studies select measures that have already been tested for reliability and validity and will include the information about this, which is a good sign. In the case of our example article, the researchers are hoping to develop different measures, so they likely won’t talk about the reliability and validity of the tools, since they’re not yet created!

Take a look at the graphic below. The first target shows arrows that are all in the same area, which describes reliability, as similar responses occur when the test is administered multiple times. In this case, although the test is reliable, it is not valid because the arrows are not near the target, which represents the variable the test is attempting to measure. The second target shows a test that is both reliable (provides similar results each time) and valid (measures what it is supposed to). The third target is neither reliable nor valid, as the arrows are all over the place, and not near the target in the center. Generally quantitative studies that show more reliability and validity, are thought to be of higher quality.

Okay, back to our example study. In the first part of the Method section, recruitment and participants are described. The authors worked in conjunction with the ACA to contact camp directors and have them share the online survey with their camp alumni. In total, responses were collected from 427 participants.

Next, the instrument, or tool used to collect data, is discussed. This was an online survey that included short answer and questions, and Likert-style questions. Likert-style means that participants were asked to respond to statements on a scale, which was from 1-4 (least to most). Each of the three elements of investigation had their own separate section on the questionnaire. These sections are the different questionnaires (measures) the authors are trying to create (purpose number one!). Skill development was a 43-question section (eventually narrowed down to a 12-item scale), elements of positive youth development included 7 questions, and antecedents of change was 14 questions. The Methods part also discusses the types of elements or factors that were examined in each of the three sections, concluding with a piece on the interactions or relationships between each of these parts.

Important to note here, this is a retrospective pretest format. This means the participants (who were all camp alumni) were comparing themselves at the time of the survey to how they were prior to attending camp. This is great because it allows participants to reflect on their experiences, however it is susceptible to response bias, meaning participants may give the answer they think the researchers want to see.

Again, if all of this sounds a little too “sciencey” for your liking, feel free to skip ahead to the results and discussion sections.

Step Five: Examine the Results

As I previously mentioned, if you’re unfamiliar with the analysis of quantitative data, it might be best just to skip ahead to the discussion section. Sometimes technical jargon is used and it can be pretty tricky to wade through it if you have no idea what it means. If you want to try to understand, that’s awesome! Take your time and again, don’t be afraid to use your favorite search engine to look up what certain tests and analyses are.

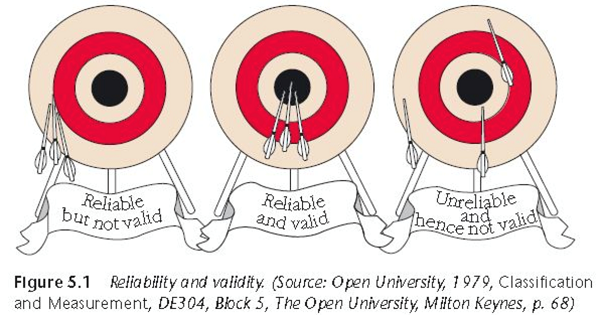

Here’s an easy example. If the paper used a correlational method, often times a matrix will be included with different variables that were examined. The chart will list different variables and a number. The closer that number is to 1, the stronger the two variables are linked. If it’s a positive number (i.e. 0.56 or 0.87), it means the two variables are positively linked and as one increases, so does the other. If it’s a negative number (i.e. -0.68 or -0.92), the two variables are negatively linked and as one increases, the other decreases. Often times correlations that are considered strong or relevant have an asterisk beside them. Take a look at the example below. Self-esteem and number 2 (extra-curricular activities) were positively correlated, meaning, as students’ participation in extra-curricular activities increased, so did their self-esteem. Cool, right?

(Diagram from: Creswell, J. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. (5th ed.) New York, NY: Pearson.)

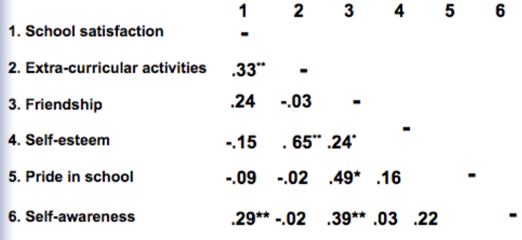

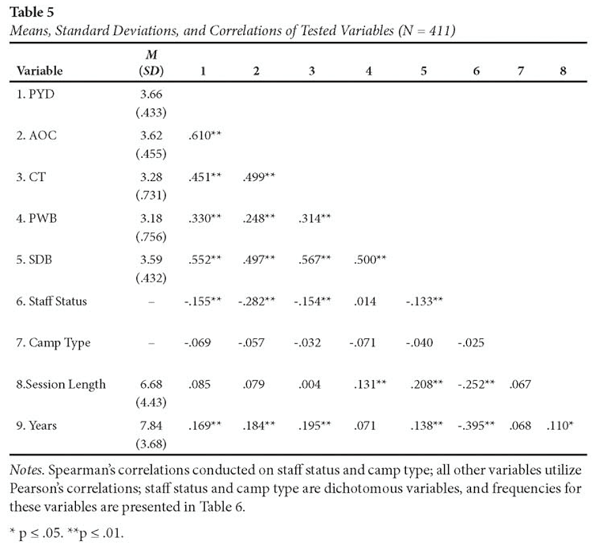

In regards to our example paper, take a look at the following matrix and see how each of the tests correlated with one another. Remember, statistically significant correlations are marked with asterisks. Acronyms are used as variables so I’ve spelt them out here.

PYD = positive youth development

AOC = antecedents of change

CT = critical thinking

PWB = physical well-being

SDB = self-determined behavior

As you can see, many of the scores were positively correlated, and significant. Let’s take, for example, SDB (self-determined behavior, which is described more on p. 188 of the paper) and PYD. As scores on the scale measuring self-determined behavior increased, so did scores on the positive youth development measure, meaning participants who felt their camp experience provided more elements of a PYD setting (i.e. opportunity for skill building, supportive adult relationships, etc.) also felt they developed more self-determined behavior (i.e. confidence, self-efficacy, competence, etc.) through their experiences at camp.

Step Six: Connect Ideas from the Discussion and Future Directions Sections

Here’s the part where we talk about how the findings from this study may have the potential to impact your camp and how you do things. Typically, in the discussion and future direction sections, the authors will explain the most important findings again and provide suggestions for how readers can potentially change applied practice and inform future research studies.

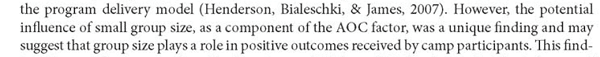

Take a look at this example from our current study:

The authors mention that in this study, small group size may have led to more positive outcomes, as reported by participants. With this piece of information, think about how you can change group sizes in your program. While cabins and living spaces may not be easy to change, think about how you can make small group sizes for arts and crafts sessions, team building activities, or creative performances. Not every camp or youth program will be able to use this suggestion, but try and think outside the box and consider what may work for you!

Step Seven: Read the Conclusion and Give Yourself a Pat on the Back!

The conclusion often summarizes the purpose of the study, the methods of data collection and analysis, the results and a few key points from the discussion. Sometimes the authors will refer to other studies that build upon their findings or maybe make suggestions on future studies that would contribute to this field. If the paper really interested you, make sure to look at the reference section to see if anything else catches your eye. You never know, you might see an interesting title and want to return to step one!

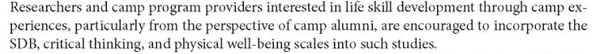

Our example study points to directions of how camp professionals can incorporate findings from this study in their future work.

That sounds like something to consider. If you’re interested in what type of outcomes your campers get from your youth program, you might want to reach out to the authors for a copy of the survey used and consider asking some of your alumni to participate in an online survey. This way you can see what campers feel they gain from your program, and maybe use those results to consider ways to improve your camp in the areas that don’t provide as much growth as you would like.

Okay — you did it! Congratulations! Again, feel free to take a look the recently updated ACA camp-related research bibliography to read more research studies. Hopefully with all this newfound knowledge, you’ll be reading studies and implementing changes in your programming in no time!

Thanks again for reading and see you next time!

Victoria Povilaitis, a research assistant for ACA, is a doctoral student at the University of Utah and has worked in the camp industry in a variety of roles, including staffing coordinator, athletic director, and sports coach.

Photo courtesy of Buckley Day Camp in Roslyn, New York.

Thanks to our research partner, Redwoods.

Additional thanks goes to our research supporter, Chaco.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Camp Association or ACA employees.