Hey everybody!

Welcome back! If you read my last post, you’ll remember that one of the reasons why I got involved with camp research is because I want to make sure it’s practical and applicable for camp professionals. There’s a ton of camp-related research out there already, and I want to encourage you to read a few studies and see how you might apply the findings to your youth program.

To make things easier to understand, I will be discussing qualitative research in this blog and quantitative research in my next one. Here’s a quick way to explain the difference between qualitative and quantitative research: qualitative = words, quantitative = numbers. I encourage you to read a few studies of each type of research and see which makes more sense to you.

I know reading research can be daunting and you might have no idea how to begin reading articles, or how to even access them! Sometimes you can read an article and think “I have no idea what this means or if it’s a good study.” Well, have no fear! Laurie Browne has already put together this great blog on “geek speak” to help you understand some research terms. If you want to engage with research, I’ve created this easy guide to help you move from finding papers online to reading them, and ultimately implementing the suggestions in your own programs. Hope it helps!

Step One: Find the Article

Some publications are free and available online, while others require paid access. An easy way to search for articles is to go to Google Scholar and type in the title of the paper. If the article does not come up, many journals provide access to papers published in previous issues in their online database. Try looking at what journal the paper is published in and search for the journal’s website, then look up the specific volume and issue the article was published in.

A typical article cited in APA format looks like this:

Author(s) (year published). Title of article. Journal name, volume(issue), page numbers if published in print. DOI.

For example, let’s take "The Developmental Importance of Success and Failure Experiences at Summer Camp," a recent article published by Cait Wilson and Dr. Jim Sibthorp from the University of Utah. The citation for this article is as follows:

Wilson, C. & Sibthorp, J. (2017) The developmental importance of success and failure experiences at summer camp. Journal of Youth Development, 12(3), 18-36. DOI: 10.5195/jyd.2017.502.

Let’s use it as our example. Enter the title “The developmental importance of success and failure experiences at summer camp” into the search bar at Google Scholar. If you click on the article link, it will take you directly to the journal’s website, and information for the paper. In this case, we are redirected to the Journal of Youth Development.

Step Two: Look at the Abstract

A quick way to see if an article is of interest to you is to read the abstract. This is always found at the very beginning of the paper and includes a quick summary or overview of what the paper is about. Typically, the information in the abstract will be presented in this order: identifying the topic, background information and literature review on the topic, aim or purpose of the study, participants and methods, results/findings, discussion and/or implications for the future. While not every abstract has each element, most abstracts follow that general outline and give the reader a basic overview of the study. This should allow the reader to determine if the paper would be interesting and applicable to them.

For our example article, the abstract gives some great information. Young people experience success and failure and these experiences help them learn skills such as perseverance and coping. Sometimes failure might hinder youths’ development, and there’s a theory to help explain this: appraisal theory. Camp is a location where kids have these types of experiences, but not much research has been done in this environment so far. The aim of the study was “to use summer camp as a context to describe youths’ appraisals of success and failure experiences and the associated development” (Wilson & Sibthorp, 2017, p. 18). The results explain how these experiences help campers develop different life skills, but sometimes failure experiences might inhibit this growth. Implications for practice are discussed in the article. Wow — seems pretty interesting to me! Let’s read it. Click on “PDF” to open the file with the whole article.

If, on the other hand, you read the abstract and didn’t think the paper sounded interesting, applicable, or understandable for you, no sweat. Try another one!

Step Three: Read the Introduction

The introduction is a great section for camp professionals to read for a few different reasons. First, it gives you some great background information on different types of theories that may be applicable to your organization or program, and it also often gives a literature review. This is the section where different studies are explained that have been completed in the same environment, with the same theory, or with the same type of participants. Hint: if any of these studies sound cool, look at the reference beside it (author names and date of publication) and go down to the reference section. Here you’ll find the citation for that study and boom — you’re back at step number one! Try to look up that article too.

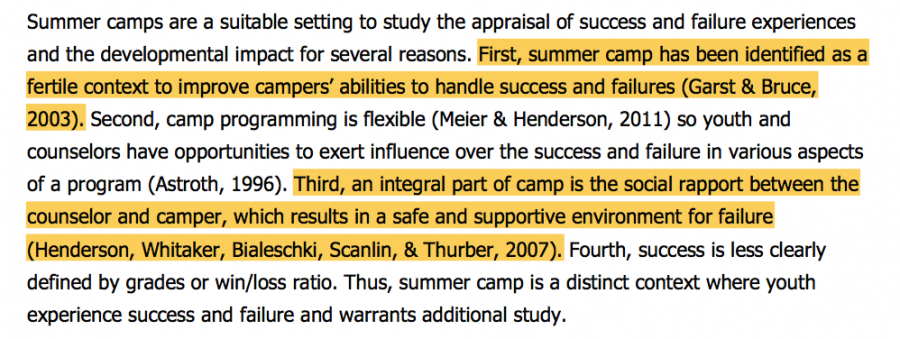

In our example paper, I really enjoyed the last paragraph of literature review in the introduction. I took the liberty of highlighting a few references that I thought would be interesting to follow up on. Take a look at this image.

So, to the reference section I went! Lo and behold, here they are! I’ve screenshotted the references here for your convenience. If you wanted, you could follow up and find these articles online and have a read through them too.

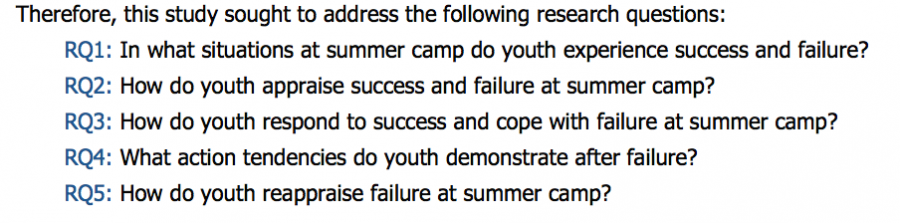

Typically, the introduction section concludes with the purpose, aim, or research questions that guide the study. For this paper, it’s very clearly laid out. We know exactly what the researchers were looking for.

Step Four: Check out the Methods

The methods section will give you a great idea of whether the study was quantitative (i.e. numbers) or qualitative (words), information about its design (e.g., case study, longitudinal, correlational, etc.), the individuals that participated, and how the data was collected.

For anyone who doesn’t have a background in research methods, often times this section is easier to understand for qualitative studies. Authors typically discuss interviews, focus groups, and observations as their data collection methods, and coding as a form of analysis (finding different themes that were repeatedly discussed).

One key point to mention is study quality, so to speak. Keep in mind, Laurie Browne wrote a great piece on bias, which may impact a study’s quality. For qualitative studies, papers might explain how credibility and trustworthiness were ensured. There may be terms such as triangulation of data, which means data collected from various sources all displaying similar themes, or inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability is when multiple researchers analyze and code (theme) the data separately, and then meet to reach consensus on these codes. The closer this number is to 1.00 or 100 percent, the more agreement there was between researchers on the themes that were present in the data.

Generally, qualitative studies that demonstrate more triangulation of data and inter-rater reliability are thought to be of higher quality.

Step Five: Examine the Results

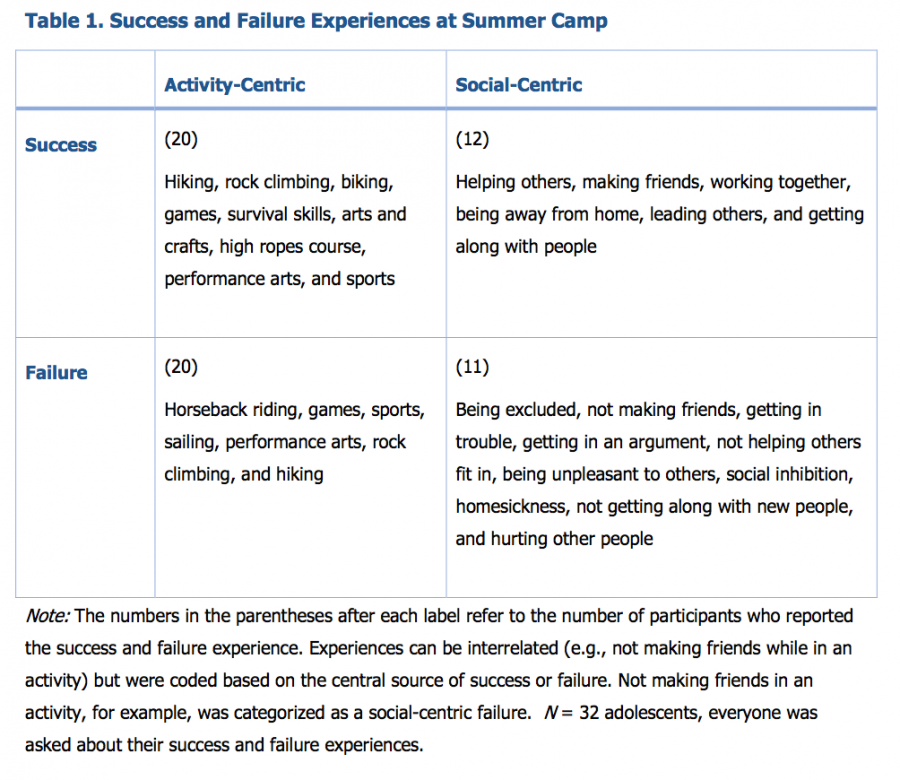

Qualitative studies often include charts or tables based on themes with example quotations from participant interviews or focus groups, termed “evidence.” Sometimes, the participant quotations are weaved into the paper, like in this case. Wilson and Sibthorp (2017) chose to organize the results according to the research questions they described at the beginning of the article. In response to research question 1, they included Table 1 detailing themes, which were examples of success and failure.

Take a read through the rest of the results section and see if anything stands out to you as interesting or maybe even unexpected.

Step Six: Connect Ideas from the Discussion and Future Directions Sections

Okay, I know we haven’t talked much about how you can take information from research studies and actually apply it to your own programming, so here we go! The discussion section is where authors review the findings from the current study, and make links between their results and previous research. They often talk about future directions, and depending on the journal, real-world applications for practitioners. At this point, I encourage you to read an article’s discussion section and think about how the findings may apply to your youth program.

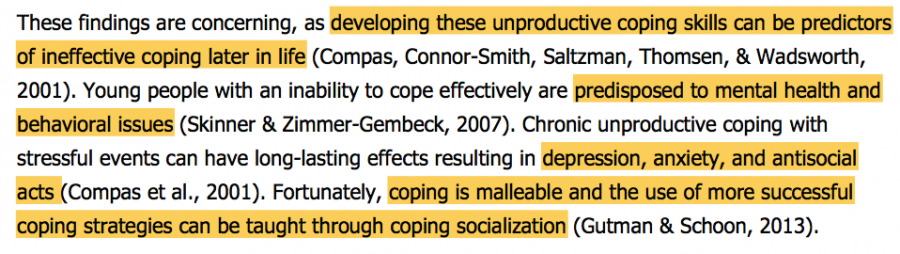

Let’s take a look at our success and failure study. There’s one paragraph that details some potential negative consequences of poor coping skills. I’ve highlighted them for us.

Yikes, that does not sound good. We definitely don’t want kids to leave our programs with poorly developed coping skills. But hey, good news! We can teach youth these skills at camp. Woohoo! How do we do that? Let’s read on…

Wilson and Sibthorp (2017) continue to discuss coping socialization, flexible goal adjustment, and reappraisal, offering some good suggestions along the way. For example, in the section on flexible goal adjustment they say, “program staff may consider ways for youth to reflect on both implicit and explicit goals after failure and reshape participant’s unrealistic goals for novel activities to be more realistic” (p. 29). This can definitely be taken and applied to real camp situations! How can staff help campers reflect on their goals? Better yet, how can you as a camp professional teach staff how to do this with campers?

While there are many great tidbits of info in the discussion section, I want to focus on this paragraph and the highlighted statements.

From my perspective, these two statements get at exactly what we want to teach new staff during orientation: how to interact with kids and help them grow at camp. While some staff have a natural talent and can easily interact with campers and create a supportive environment, others may need a bit more practice. Using this information about experiences of success and failure and different coping strategies, we can create an orientation session. We might start with an informational PowerPoint and include some descriptions of what success and failure look like for youth at camp, different ways we can help kids frame failure, and what to do to help them move towards success in this area. Brainstorming sessions, role play, and staff skits can help to reinforce the key messages and help staff gain more hands-on experience before the campers arrive. The possibilities are endless – find something that works for your organization and program.

Step Seven: Read the Conclusion and Give Yourself a Pat on the Back!

The conclusion usually does a nice job of summarizing the study, what was found, and how researchers and practitioners can move forward. For example, this paper brings it all together nicely: “Dedicated efforts by camp staff to help youth reappraise and frame failure experiences as an opportunity for learning may help encourage positive and productive responses to failure” (Wilson & Sibthorp, 2017, p. 32). Use statements such as those to guide how to implement research findings. In this case, come up with ways to teach your staff how to help youth understand experiences of failure as opportunities to learn.

Finally, pat yourself on the back. You read a research study and are planning to use it in your own programming. That’s amazing! Now, to actually incorporate it… step one. Just kidding!

Okay everyone, it’s time for you to try reading and implementing qualitative research on your own. As I mentioned in the last post, ACA has compiled a list of camp related studies. Take a look at the list, choose an article that might be interesting you, and begin at step one.

Thanks everyone! See you next time for the discussion of how to read and understand quantitative research. Happy reading!

Victoria Povilaitis, a research assistant for ACA, is a doctoral student at the University of Utah and has worked in the camp industry in a variety of roles, including staffing coordinator, athletic director, and sports coach.

Photo courtesy of Cheley Colorado Camps in Estes Park, Colorado.

Thanks to our research partner, Redwoods.

Additional thanks goes to our research supporter, Chaco.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Camp Association or ACA employees.