Hello camp friends, and welcome to the second in our short Research 360 series focusing on evaluation during the time of COVID-19. In our first blog we suggested that, like trees, your evaluation systems might contract as you focus on the health and safety of your camp community — and that’s OK! Those systems will expand again when things get back to normal.

But a lot has happened since that post, including a shift in how camp people are thinking about engaging their campers and camp families. Many camps are offering or planning to offer virtual programming, like evening campfires, camp craft tutorials, or online hangouts. While this is an exciting new way to think about camp, it is still new, and potentially overwhelming. Does a virtual program have different outcomes than traditional face-to-face programming? And how do we know if our virtual programs are meeting our goals?

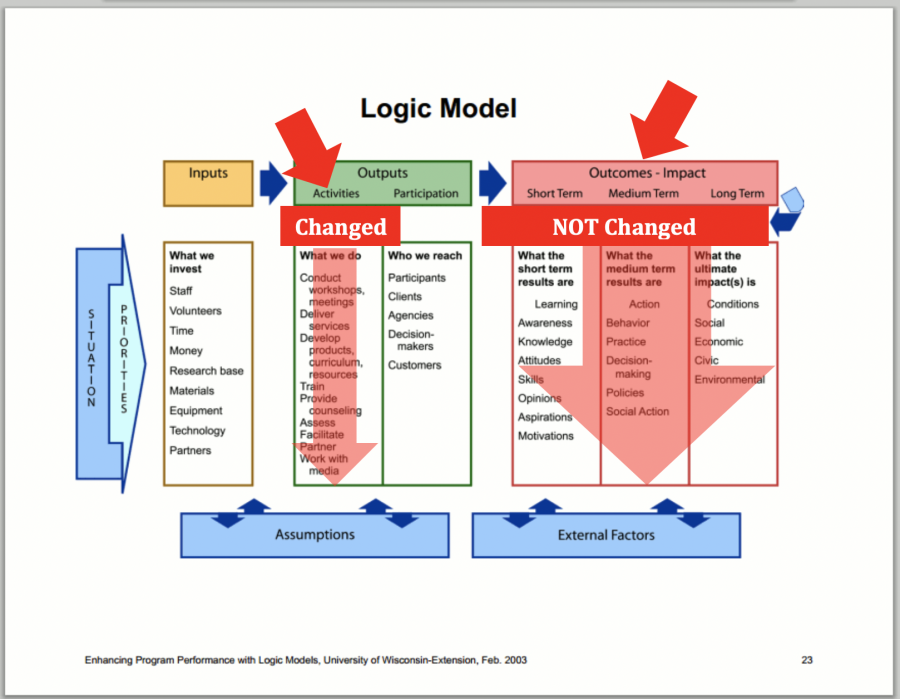

In this week’s blog post about camp evaluation during the time of COVID-19, we focus on something we’ve discussed before in previous Research 360 blogs: logic models, and looking at a logic model to decide what and how to evaluate your programming. You know evaluation is important, but what should you evaluate now that what you do is so different? Now that your programming is virtual or remote? How do you decide where to put your evaluation focus?

Before we dive in, you can find some other excellent resources on logic models here and here.

Whether it is virtual or in-person, you’re still programming! When you create a program for people, you’re hoping to change something for those people. And you program for what you want to happen. This is known as intentional programming, where you are being intentional about the specific benefits or changes the program will make for the people who engage in the program.

Intentional programming might look like a series of goals and objectives for participants. For example, some camp programs aim to “connect youth to nature” or “increase confidence” or “improve social skills.” Nature connection, confidence, and social skills are all examples of outcomes for participants — the benefits a program is expected to provide its participants. But how do these participant outcomes happen? That’s where your program comes in!

When you design a program, you’re thinking about what changes or outcomes you hope to see in participants. These outcomes probably (or should!) align with your camp’s mission. For example, if you run a sports camp, you will probably intentionally aim for your campers to increase their skills in a sport. If you run a medical specialty camp for kids with serious illnesses, you probably intentionally aim for kids to improve their social skills because your campers might not have many social opportunities in their everyday lives due to feeling sick or being hospitalized.

Now, back to what to evaluate! Review your program’s logic model or goals for participants. Keep in mind the intended outcomes or changes for participants (the right side of the logic model) while recognizing the COVID-19-related adaptions on the left side (inputs, activities, participants). If a logic model is unavailable, focus on your camp’s mission or stated program goals – what do you expect this program to change for participants? Chances are you aren’t changing your outcomes just because of COVID-19, although you might have changed your activities. What’s on the right side of your logic model doesn’t change even though what’s on the left does. That which is most important to your camp hasn’t changed at all!

Retrieved 4/6/2020 from Better Evaluation.

In our experience, we find that when there’s a new program it’s better to keep it simple and focus on (1) satisfaction with the program or (2) short-term outcomes of the program or (3) both.

- Evaluating satisfaction: Think about the indicators you might see if your program participants are satisfied with the program. Do they stay engaged for your entire Facebook Live event? Do they watch your video to the end? You can also ask them to comment or use a chat box such as “What was your favorite thing about today’s event?” or “What suggestions do you have for us for next time?” What other metrics or indicators show satisfaction?

- Evaluating short-term outcomes: Think about the immediate changes your activity or program might make for participants, in line with your camp’s mission or reason for existence. What are your goals for participants?

- Evaluating both: Check out next week’s blog for tips for how to evaluate virtual and alternative programming!

This can also be called a “developmental” approach to evaluation, meaning that evaluation is rapidly responsive to changing contexts, goals, and needs and aims to quickly inform design and delivery of new activities and programs. Michael Quinn Patton points out we are social innovators, working in complex, dynamic systems. Better Evaluation defines developmental evaluation (DE) as an “evaluation approach that can assist social innovators developing social change initiatives in complex or uncertain environments. DE originators liken their approach to the role of research & development in the private sector product development process because it facilitates real-time, or close to real-time, feedback to program staff thus facilitating a continuous development loop.”

Remember, evaluation should be about celebrating and encouraging a learning culture at your camp. Don’t worry too much about the potential long-term impacts of your brand-new programming. Focus on meeting your mission and improving the outcomes of your program for your participants, and then exploring new (and maybe virtual) ways of meeting those goals.

Most importantly, remember that it’s OK to keep your evaluation simple while you navigate these uncertain times. We’ll suggest some simple ways you can collect evaluation information in virtual formats---some of which might even be easier online than in traditional programming.

Until then, be well!

Laurie Browne, PhD, is the director of research at ACA. She specializes in ACA's Youth Outcomes Battery and supporting camps in their research and evaluation efforts. Prior to joining ACA, Laurie was an assistant professor in the Department of Recreation, Hospitality, and Parks Management at California State University-Chico. Laurie received her PhD from the University of Utah, where she studied youth development and research methods.

Ann Gillard, PhD, has worked in youth development and camps for more than 25 years as a staff member, volunteer, evaluator, and researcher.

Thanks to our research partner, Redwoods.

Additional thanks goes to our research supporter, Chaco.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Camp Association or ACA employees.