Considering Access to Summer Camp is a four-part series that highlights recent research aimed at helping camp practitioners increase access to summer camp for all youth. The first article introduced summer camp as a developmentally enriching experience, the opportunity gap, and how we conceptualize factors that impact participation (what we call “constraints”). The second article took a deep dive into constraints and how they are shaped by culture. The most-recent, third article considered the important role that preference plays in accessing summer camp programs. This final installment pulls together everything we’ve learned to try and help answer the question: How can practitioners help families overcome barriers to participation in their summer camp programs?

You can find the first three articles in this series here:

- “Considering Access to Summer Camp”

- “Considering Access to Summer Camp, Part II: What Impacts Access to Summer Camp?”

- “Considering Access to Summer Camp, Part III: Understanding Preference for Summer Camp Programs”

Throughout this series, we have used a range of terminology to describe what we’ve learned. The following lexicon defines and clarifies what we mean when we use these unique terms.

Lexicon

Constraints: All the factors that impact participation in summer camps, including preventing participation; reducing frequency, intensity, or duration of participation; or reducing the quality of experience or satisfaction gained from participation in summer camp. Constraints are categorized in three ways: psychological, social, and structural — and all are shaped by culture.

Negotiate: Traditionally meaning “to find a way over or through (an obstacle or difficult path),” in current constraint literature, when one works through or around a constraint, they have “negotiated” it. Put another way, they may have overcome an obstacle or navigated some sort of barrier to access.

Obstacles: Another word for constraints. Examples include poverty, distance between home and camp, transportation, childcare for younger siblings, and time.

Opportunity Gap: “Refers to inputs — the unequal or inequitable distribution of resources and opportunities,” such as differences in family income, wealth, and neighborhood resources; institutional and systemic sources of inequity; and racism, bias, and discrimination (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2019; Glossary of Education Reform, 2013). By highlighting the numerous obstacles children face over the course of their development, this term shifts the responsibility from youth and more accurately places it on systems of inequity that are not providing the opportunities for all children to thrive and succeed (Mooney, 2018).

Socioeconomic Status (SES): The social standing or class of an individual or group. It is often measured as a combination of education, income, and occupation, and frequently reveals inequities in access to resources and issues related to privilege, power, and control (APA, 2021).

Constraints to Summer Camp, a Review

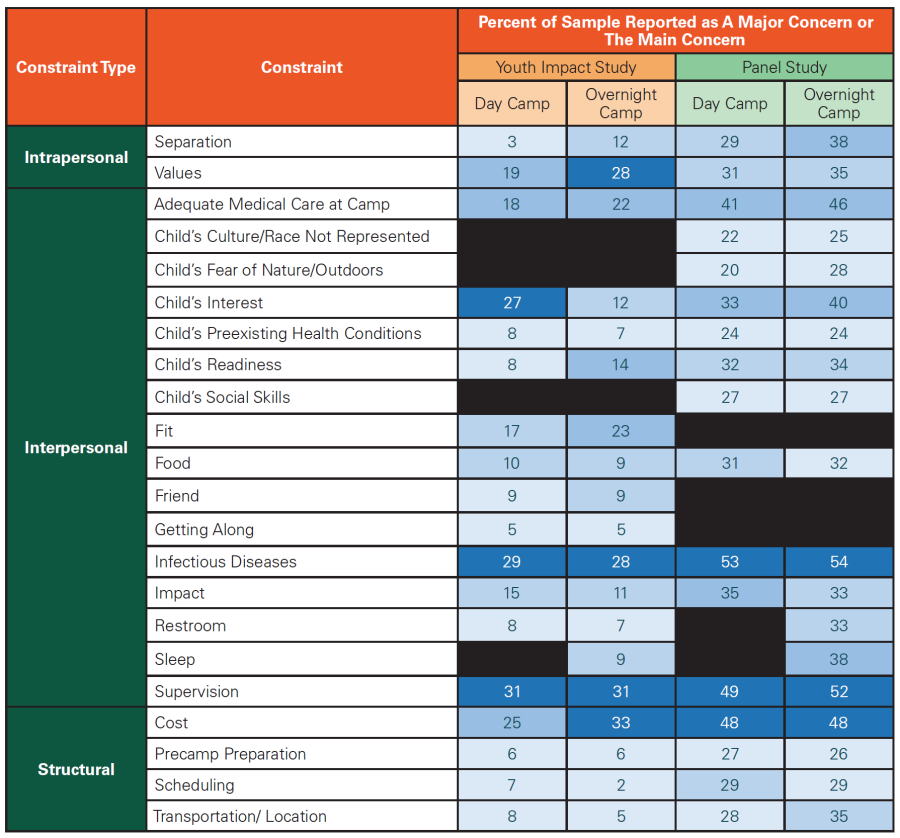

As we have articulated throughout this series, there is an opportunity gap when it comes to accessing summer camps. Throughout our research, we have conceptualized the gaps, or obstacles, that families face when attempting to access summer camp as constraints. Constraints may be defined as any factor that negatively affects voluntary leisure participation (Henderson et al., 1996) by reducing the frequency, intensity, or duration of participation in the activity; reducing the quality of experience or satisfaction gained from participation in the activity; or preventing participation in the activity altogether (Goodale & Witt, 1989). Constraints may also be categorized as either intrapersonal (i.e., psychological factors), interpersonal (i.e., social factors), or structural. Through our research (via an initial pilot study, ACA’s ongoing national Youth Impact Study, and our 2020 winter Panel Study; see the second article in this series for details about each of these studies) we were able to identify parents’ most salient constraints when thinking about sending a child to summer camp. Results are presented in Table 1.

Note: Due to differences the research questions and methodologies utilized in the Youth Impact Study and the Panel Study, the constraint categories are not parallel. For example, whereas the Youth Impact Study had discreet categories for “Friend” and “Getting Along,” these were combined into “Child’s Social Skills” for the Panel Study.

While we don’t want to dive too far into the weeds of these studies, we do want to highlight one important finding to carry forward in this discussion: constraints vary. Looking at Table 1, you can see that the percentage of parents reporting high levels of concern for certain constraints to day camp often differs from the percentage of parents reporting high levels of concern for the same constraints to overnight camp. Thus, constraints vary based on program type. Results from these studies are also consistent with previous research demonstrating that constraints vary depending on different social factors, such as one’s socioeconomic status (SES) or their social identity (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation; Dickerson, 2021; Wycoff, 2021).

Strategies for Negotiating Constraints to Summer Camp

Importantly, constraints do not necessarily prevent participation in voluntary activities (Jackson et al., 1993). Research suggests that when faced with constraints, many individuals successfully use different strategies to work around them, resulting in partial or full participation (Crawford et al., 1991; Henderson & Bialeschki, 1993). So, along with identifying the most concerning constraints families face when attempting to access summer camp, our studies sought to identify the most promising strategies for negotiating those barriers.

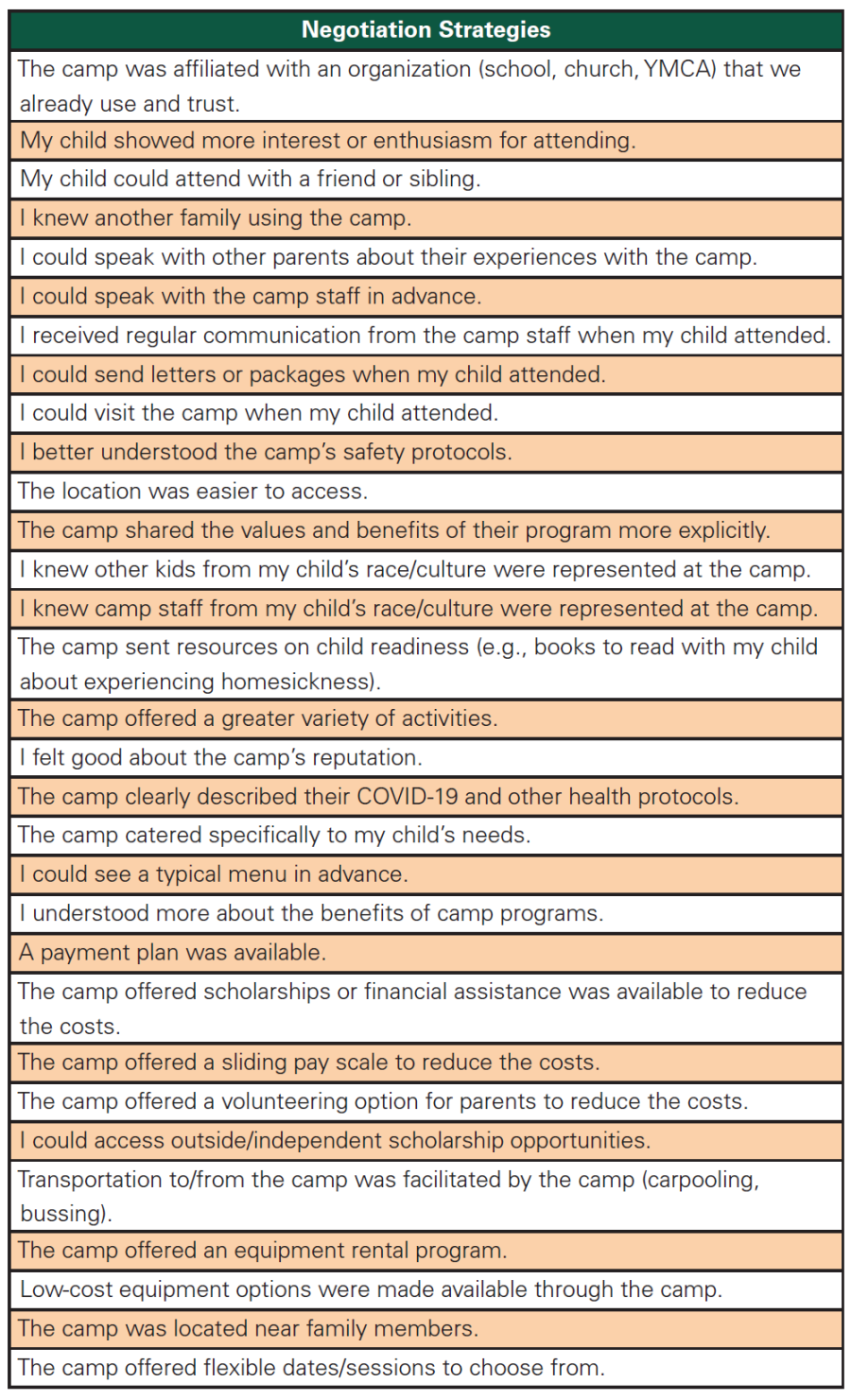

To do this, we began by asking interview participants in the Youth Impact Study to share their strategies for negotiating the constraints they identified as most worrisome on their surveys. From these results, we developed a list of common negotiation strategies parents (might) utilize when considering sending a child to summer camp. Then, to strategically link constraints and negotiation strategies, for any constraint parents in the Panel Study identified as “A Major Concern” or “The Main Concern,” they were provided a list of appropriate negotiation strategies (drawn from the results of the Youth Impact Study) and were asked to select up to three strategies that were most likely to reduce their levels of concern. The full list of potential negotiation strategies developed from and utilized in these studies is presented in Table 2.

Much like our findings regarding constraints, we found that negotiation strategies are both simple and complex — for just as constraints vary, so, too, do negotiation strategies.

Negotiation strategies may vary based on the constraint in question. For example, while organizational affiliation was most likely to alleviate parental concerns regarding whether or not camp aligned with their family values, being able to see a menu was considered more helpful when concerned about the food at camp.

The level of concern families expressed for each constraint varied based on camp type, and negotiation strategies changed accordingly. For instance, for parents of children with preexisting health conditions, knowing that a camp would cater specifically to their child’s needs was the top negotiation strategy for day camp, while speaking with the camp staff in advance was the top negotiation strategy for overnight camp.

Finally, we looked at negotiation strategies overall, independent of specific barriers. We discovered that the most common negotiation strategies across all constraints and program types were organizational affiliation and child interest.

From these studies, we have learned a lot about how camps can support families in negotiating constraints in order to attend summer camp.

Implications For Practitioners

A key component of the opportunity gap is shifting the burden of responsibility from individuals to the systems of inequity that are failing to provide the necessary opportunities for success. Therefore, practitioners cannot, and should not expect families to negotiate constraints on their own. Rather, summer camps (both as individual organizations and as a social institution; see Browne et al., 2019) need to be proactive about addressing the obstacles families face when attempting to access their programs.

More specifically, results from the Panel Study suggest that all camps would benefit from addressing parental concerns about infectious diseases, supervision, adequate medical care at camp, and cost. To do this, camps can:

- Share a clear description of their health protocols (specifically COVID-19 protocols at the time of these studies)

- Highlight their camp’s reputation and any organizational affiliations

- Share their safety protocols

- Offer scholarships, payment plans, or other forms of financial assistance

If your camp is already doing these things, it may be worth asking how readily available this information is to current and prospective camp families.

While the aforementioned constraints were consistently among the top most-concerning constraints reported by parents in our studies, it is important to remember that constraints vary. This variation can potentially affect the negotiation strategies of interest to each camp. Thus, we want to again emphasize the value of narrowing in on your target audience before you attempt to identify potential obstacles to accessing your summer camp programs and the negotiation strategies your camp may want to prioritize to help those attempting to access your summer camp programs.

All kids should have access to developmentally enriching programs, like summer camp. While summer camp might not be the best fit for every youth, we believe there is a camp for every family who wants to include it as part of their summer strategy. Working together, we are confident that researchers and practitioners alike can help families of all backgrounds and circumstances access and enjoy the benefits of summer camp participation.

Photos on pages 13–14 courtesy of Teton Valley Ranch Camp, Dubois, WY; and YMCA Camp Grady Spruce, Graford, TX.

Taylor M. Wycoff, MS, is a recent graduate of the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program at the University of Utah. She serves as a research and evaluation specialist on ACA’s Research Team.

Jessie Dickerson, MS, is a recent graduate of the Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Program at the University of Utah. She is a grants and special projects manager for ACA’s Research Team.

References

Browne, L. P., Gillard, A., & Garst, B. A. (2019). Camp as an Institution of Socialization: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Experiential Education, 42(1), 51-64. doi.org/10.1177/1053825918820369

Crawford, D. W., Jackson, E. L., & Godbey, G. (1991). A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 13, 309-320. doi.org/10.1080/01490409109513147

Dickerson, J. (2021). How Families Negotiate Access Constraints to Summer Camp. [Master’s Thesis, University of Utah]. USpace Institutional Repository.

Goodale, T. L., & Witt, P. A. (1989). Recreation non-participation and barriers to leisure. In E. L. Jackson & T. L. Burton (Eds.), Understanding leisure and recreation: Mapping the past, charting the future (pp. 421-449). Venture Publishing.

Henderson, K. A., & Bialeschki, M. D. (1993). Negotiating constraints to women’s physical recreation. Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure, 16(2), 389-412. doi.org/10.1080/07053436.1993.10715459

Henderson, K. A., Bialeschki, M. D., Shaw, S. M., & Freysinger, V. J. (1996). Both Gains and Gaps: Feminist Perspectives on Women’s Leisure. Venture Publishing Inc.

Jackson, E. L., Crawford, D. & Godbey, G. (1993). Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409309513182

Mooney, T. (2018). Why We Say “Opportunity Gap” Instead of “Achievement Gap.” Teach For America. teachforamerica.org/stories/why-we-say-opportunity-gap-instead-of-achievement-gap

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2019). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. (M.-J. Sepúlveda & R. Hutton, Eds.). The National Academies Press. doi.org/10.17226/25546

Wycoff, T. (2021). Helping Camps Provide Accessible Summer Programming: The Role of Income, Race, and Preferred Negotiation Strategies in Constraints to Participation. (Publication No. 28718495) [Master’s Thesis, University of Utah]. USpace Institutional Repository.